Figure 2.11: Big game. Source: Florence Guiraud

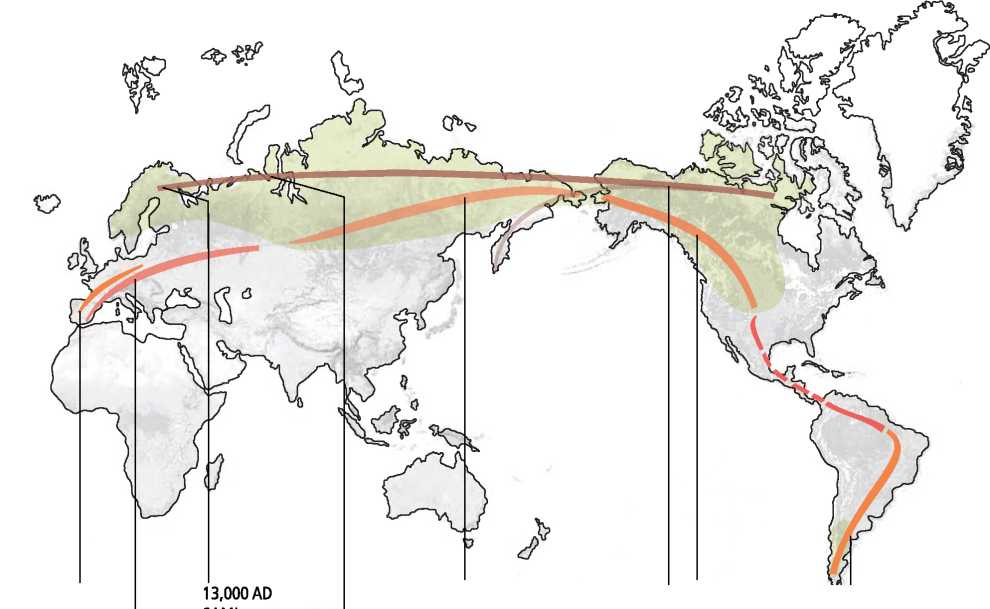

40,000-26,000 BP

15,000-11,000 BP MOLODOVA

10,000-1800 AD PLAINS INDIANS

With the warming of the climate and the growing of the forest in Europe, the big animals gradually moved eastward into Inner Asia, with woolly mammoths, wooly rhinoceroses, and tigers roaming the region among herds of horse, bison, muskox, and Siberian antelope (Figure 2.11).

13,000 AD SAMI

26,000-15,000 BP GRAVEniAN

14,000-1900 AD NENETS

1000-1800 AD ENUITS

10,000-1800 AD TEHUELCHE

Humans had a choice, to follow or to stay. Those who stayed are known as the Magdaleniens. They developed a complex hunting and plant-gathering, ritual-oriented society suited to forest life. Most people probably followed the game, remaining closer to their Gravettian roots. The center of gravity of this hunting culture moved rapidly to northeast Asia and then finally crossed into the Americas.

Thus expanded, the big game hunting culture formed a huge arc from Russia and Finland to the Americas. In some places, the tradition survived into the nineteenth century to include the Saami in Finland, the Plains Indians in the Americas, the Inuits in northern Canada, and even the Tehuelche in southern Argentina, who until their final biological and social annihilation due to pressures exerted by the European conquest and colonization represented the far reach of the great hunting tradition. We will discuss these various people in more detail later, but for the moment one has to acknowledge the sweeping, transcontinental and trans-temporal continuity that the big-game hunting tradition constituted. With it, spread not only certain types of technologies like sewing, but an organizational focus that linked the human and the non-human world of animals, moons, stars, and landscapes into a tight ritualist and cultural package.

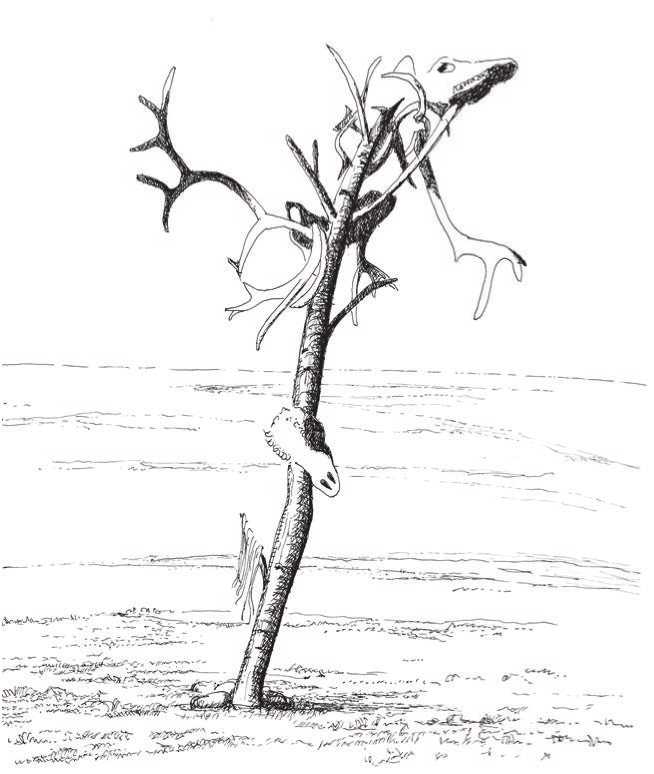

Figure 2.12: Reindeer herder spirit post, Siberia, from early twentieth-century photograph. Source: Mark Jarzombek

From anthropological studies, it is clear that hunting even in archaic times was never just a question of food. The first hunt in a young man’s life was a memorable event of coming of age; it was inevitably accompanied by ceremonies and rituals. Ancestor spirits played an important part. They could take on animal forms and were summoned in trances to help guide the hunter. Lapp legends describe a golden-antlered deer that serves as a protector and guide. When the Ostyaks lured a bear out of its lair, they would say, “Don’t be angry, grandfather! Come home with us and be our guest.” When they killed the bear they would beg it not to resent their action and take revenge. Some even would try to ritualistically escape blame for having killed an animal. The Sami would “convince” the bear that it died by its own fault, or blame it on a bad weapon.

Certain animals are considered to be totems or symbolic ancestors for tribes or clans, such as the Blue Wolf and the Red Deer, the mythical ancestors of the Mongolians. The western Buryats of Siberia recognize a bull, Buh Noyan Baa-bai, as their ancestor. Other tribes recognize the swan, the wild boar, the burbat fish, or the eagle as their totemic ancestor, so that special care must be taken not to harm these animals.12

Hunting was inevitably connected to a host of taboos and preparations. Earth spirits exist that can function as an animal’s guardian but may also protect the hunter from danger. In some cases such spirits, if not properly respected by the execution of specific assuaging activities, can “capture” the hunter by making him loose his way.13 The Caribou Eskimos take ritual precautions to secure the catch and to promote future hunting success by attempting to appease the souls of the killed animals. They also hold that the spirits would get angry if too many caribou were killed wantonly so that their lefi:overs were consumed by scavengers such as foxes and ravens. A general principle prevailing among Arctic hunters was that the animals’ spirits had to be respected. In evidence of that, hunters believe animals prefer to be caught by people whose clothes and equipment were ritualistically clean. The Iglulik Eskimos clean their hunting gear and clothes in the smoke of burning seaweed before they set out sealing.14 In some places women, during the hunt, have to stay indoors and keep their lamps extinguished. After the catch, gifts are made to appease the spirit of the hunted animals. Siberian hunters construct spirit posts made of a tree limb planted in the ground and ornamented with animal skulls and ribbons of cloth (Figure 2.12). All in all it would be wrong to assume that hunting was simply about the tracking and killing of animals for food and resources. Hunting was deeply entwined with notions of the spiritual well-being of both animals and humans; in other words, the hunter had to visibly and respectfully demonstrate his recognition of the natural continuum and interconnectedness of all natural phenomena.

World History

World History![Road to Huertgen Forest In Hell [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432477693_1428700369_00344902_medium.jpeg)