The arguments of Berry and Berry notwithstanding, many Southwest archaeologists support the position that the Early Puebloan people developed from Oshara tradition and other Late Archaic groups who practiced incipient agriculture across the northern Southwest. Although local temporal sequences have been developed for a number of areas, the generalized Pecos Classification (developed by A. V. Kidder in 1927) is still used by most archaeologists to provide regional consistency and for reference (Table 2). The first period defined for the ancient Puebloans is Basketmaker II, which, as discussed above, overlaps the latter portion of the En Medio phase as defined by Cynthia Irwin-Williams.

Basketmaker II Period (600 BC-AD 500)

The Basketmaker II period is dated between 600 BC and AD 500 in different parts of the northern Southwest. Basketmaker II, as currently defined at maximum, then, is as long as the remainder of the ancient Puebloan sequence. Basketmaker II is a critical stage in Puebloan development because it was during this time that the use of cultigens became a significant part of subsistence. The spread of agriculture, in turn, led to a more sedentary lifestyle. General traits of the period include construction and use of small pit houses, large storage cists, shallow grinding slabs, corner and side-notched dart points, the atlatl, one-hand manos, and cradleboard burials. The importance of agriculture, along with the initial use of ceramic containers, is what separates the Puebloans during the Basketmaker II period from earlier and contemporary Archaic populations. Figure 5 Illustrates Early Pueblo corn agriculture with use of a digging stick.

Various models relating to the adoption of agriculture among the Puebloans have been proposed, many of which have overlapping elements. From an evolutionary point of view, the adoption of agriculture may be seen as providing a selective advantage for the Puebloans that the gathering of wild plant foods did

Table 2 A. V. Kidder's 1927 Pecos Classification. Modified for the Four Corners region of the American Southwest

Period | Dates |

Basketmaker II | 600 BC-AD 500 |

Basketmaker III | AD 500-750 |

Pueblo I | AD 750-900 |

Pueblo II | AD 900-1150 |

Pueblo III | AD 1150-1300 |

Pueblo IV and V | Post AD 1300 |

Figure 5 Depiction of early Puebloan corn agriculture using a digging stick. Salmon Ruins Museum collection.

Not. In the absence of strong selective pressure, explaining why the use of cultigens would have become important is difficult. The most important selective advantage of cultigens is their dependability and predictability as contrasted with natural plants. Thus, initial use of cultigens probably relates to their seasonal predictability in given areas. It has also been suggested that hunter-gatherers who could most easily fit the demands of cultivation into their seasonal rounds would be most likely to practice agriculture. There are, of course, other parameters involved in the adoption of agriculture, but for the present discussion, understanding that the predictability of cultigens was a key factor is sufficient. In any case, there is good evidence that the Early Puebloans in certain areas (e. g., Cedar Mesa, Utah and Black Mesa, Arizona) were largely dependent on maize agriculture by the Early Basketmaker II period.

Recent work has broadened our understanding of the Late Basketmaker II period, and the transition to Basketmaker III and Pueblo I. Using data from a project on the Rainbow Plateau of Arizona, Phil Geib and Kimberly Spurr identified perhaps the earliest use of pottery in the northern Southwest at AD 200. They also found good evidence of the transition between Basketmaker II and III between AD 200 and 450, filling a gap that Mike Berry and other archaeologists had identified. Geib and Spurr identified maize-dependent groups during the Basketmaker II interval. Other findings were related to turkey domestication and early use (by about AD 200) of the bow and arrow. Perhaps the most important contribution Geib and Spurr made is the understanding that the transition from Basketmaker II to III was not a smooth, coordinated process. The traits they discussed - initial manufacture of pottery, dependence on maize agriculture, use of the bow and arrow, turkey husbandry, and the introduction of beans into the Puebloan diet - were not linked together as a suite and were not all introduced at the same time. Rather, these traits developed at different rates on the Rainbow Plateau and across the northern Southwest.

Studying early pottery production, Lori Reed, Dean Wilson, and Kelley Hays-Gilpin contributed significantly to a new understanding of the Late Basketmaker II and Early Basketmaker III interval. Although archaeologists have observed brown ware pottery at Puebloan sites for at least 40 years, Reed and her colleagues were among the first to address the brown ware problem regionally. Archaeologists in the Southwest are accustomed to a simple dichotomy in pottery: brown is Mogollon and gray is Puebloan. In reality, a Puebloan brown ware tradition underlies the gray in most areas. This research documented the widespread occurrence of Puebloan brown ware and proposed combining many types previously split out, offering a few combined types that bring coherence to our understanding of brown ware pottery across the region.

A large Basketmaker II population is inferred for Black Mesa, Arizona; a dramatic increase from Archaic times is apparent. By 600 BC, a firm commitment had been made to agriculture on Black Mesa. Basketmaker II settlements across the Southwest generally occur on terraces above major drainages and have been documented throughout the greater San

Juan Basin and across the Four Corners region. These sites date in the interval from 800 BC to AD 400 and most contain maize. Lithic tool kits at these Early Basketmaker sites are indicative of an Early Puebloan adaptation, with debitage, cores, and tools showing use of local raw materials. The use of stone raw materials and the core reduction strategies reflect a more constricted range of movement in the region relative to earlier Archaic people, with fast, efficient reduction of locally available stone raw materials to produce usable tools.

Basketmaker III Period (AD 500-750)

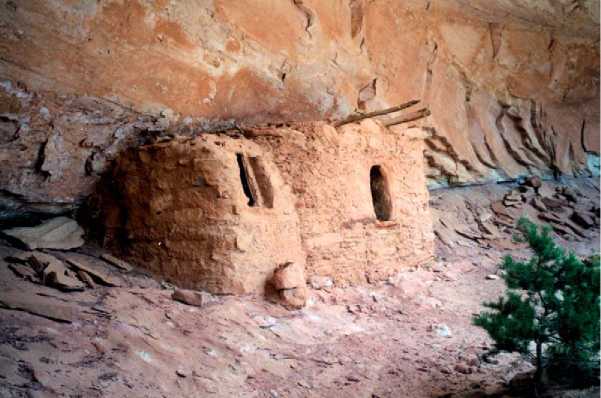

Recent work suggests that the Basketmaker III (AD 500-750) period was different than portrayed in conventional southwestern wisdom. Perhaps because of the contrast in A. V. Kidder’s original 1927 Pecos Classification (Basketmaker vs. Pueblo), southwestern archaeologists have viewed both Basketmaker periods (II and III) as transitional between the huntinggathering cultures of the Archaic period and the agricultural Puebloans, beginning in Pueblo I. In contrast, some Basketmaker II sites represent the remains of groups dependent on agriculture. Furthermore, by Basketmaker III, sedentary agricultural populations were living across the region. Such adaptations have been documented in the Mesa Verde, Colorado, area, in the La Plata Valley, New Mexico, on Cedar Mesa, Utah, and at several locales along the eastern and western slopes of the Chuska Mountains, among other areas. This revised view of Basketmaker III, with fully sedentary populations dependent on maize agriculture, is supported by recent stone tool and lithic studies, studies of pottery production and technology, and the latest rock art research. Figure 6 shows two Early Pueblo corn granaries in a rock shelter in southeastern Utah.

Basketmaker III remains in many areas of the northern Southwest apparently represent in situ continuity from Basketmaker II. Important characteristics of this period across the Southwest include large, formal pit houses, the introduction and use of the bow and arrow, two-hand manos and trough metates, gray ware and early red and unslipped white ware ceramics, and an increasing dependence on agriculture. Long, linear blocks of adobe rooms are associated with Late Basketmaker III sites. Figure 7 illustrates the floor of an abandoned Basketmaker III pithouse.

Basketmaker III sites are relatively common on southern Black Mesa and in the Low Mountain area of Arizona, but are apparently absent from northern Black Mesa. In the San Juan Basin, Basketmaker III sites are relatively common and are scattered throughout the area.

Pueblo I Period (AD 750-900)

The Pueblo I period (AD 750-900) in the Southwest is generally characterized by the extensive use of surface rooms and pueblos, constructed mostly of masonry or jacal. Kivas of various sizes where religious ceremonies were presumably held became common during this period. The widespread production and use of both neckbanded gray ware and early black-on-white painted ceramics is also a defining trait of the period. Agricultural production continued to be of importance for Puebloan subsistence. Areas with significant Pueblo I populations include Mesa Verde, Dolores area, the upper La Plata River Valley, and Chaco Canyon.

In the Western Pueblo area, Pueblo I is viewed as an elaboration of patterns established during the preceding period. This period apparently represents a time of

Figure 6 Photograph of early Pueblo granaries in a rock shelter in southeastern Utah. Photograph by author.

Figure 7 Early Puebloan (Basketmaker III period) pithouse at Cove, Arizona. Photograph by author.

Continued low population density in the Glen Canyon area. Site frequencies are low, much as they are in areas further to the north and east. It is possible, of course, that many Pueblo I sites are obscured by the more obtrusive Pueblo II deposits and simply have not been identified. In the San Juan Basin, Pueblo I sites, although not as common as those of earlier or later periods, are present in moderate numbers; because of this, little population change is inferred for the Four Corners region during this period.

Pueblo II Period (AD 900-1150)

The period from AD 900 to 1150, described as the Pueblo II period, is thought by many archaeologists to represent the apogee of ancient Puebloan cultural development. This view is due largely to the impressive remains found in Chaco Canyon (centrally located in the San Juan Basin, southeast of our Four Corners region) and the system that evolved around it. However, Pueblo II represents the time of greatest population dispersal across the entire Southwest, and much of this activity was clearly beyond the Chacoan realm.

Across the Southwest, Pueblo II is a period of dramatic increase in site frequency and population. Salient traits of the period are multiple-room masonry structures with associated kivas and formalized middens, numerous black-on-white, red, orange, polychrome, and corrugated ceramics, extensive exchange networks and the development of alliances, sophisticated agricultural practices, and large complex sites. Figure 8 Shows a Gallup black-on-white ceramic bowl.

This basic pattern is apparent in the Western Puebloan area of northeast Arizona and southeast

Figure 8 Photograph of Gallup black-on-white ceramic bowl, distinctive of the Pueblo II period. Photograph by Lori Stephens Reed.

Utah. The majority of sites in lower Glen Canyon date to this period, indicating an intensive occupation. Site location in the canyons and valleys was apparently linked to the presence of alluvium and arable land. These lowland sites appear to be relatively limited functionally. Highland sites, in contrast, exhibit more evidence of a broad range of functions and activities, and appear to have been occupied year-round. Puebloan settlement on Black Mesa peaked during this period and then declined; the area was effectively abandoned by Late Pueblo II.

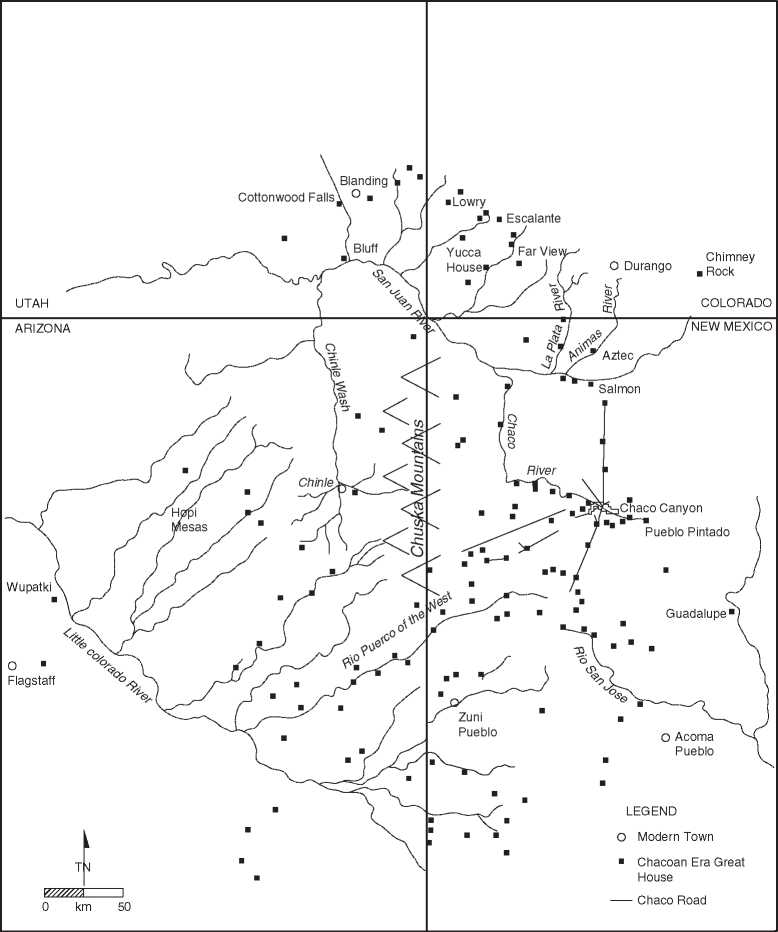

Chacoan Society during the Pueblo II Period Ancient Puebloan society in Chaco Canyon at its peak (AD 1050-1100) was characterized by a number of traits that set it apart from previous, contemporary, and subsequent Puebloan communities and sites. First, Chacoan structures, known as great houses, were built in a monumental style (with three or four stories typical) similar (but unrelated) to the European Medieval castles of the same period in the Old World. Pueblo Bonito is the largest and grandest of all the great houses (Figure 9). Chacoan great houses are distinct from the majority of Puebloan structures of earlier and later periods because of their symmetrical construction and massive architecture described as core-veneer. The massive walls (up to a meter thick) consisted of a rubble, dirt, or masonry core with inner and outer veneers of carefully selected, shaped sandstone slabs (Figure 10). The imposing size and height of these structures, and other factors, support the idea that the great houses were landscape monuments (in addition to having other functions). As monuments, the great houses were intended to impress and awe local residents, as well as outsiders.

One of the more compelling aspects of the Chacoan landscape was the network of roads that were constructed between about AD 1050 and 1100. Perhaps 400 miles of roads have been detected using aerial photography and many segments have been ‘ground-truthed’, - confirmed by a field inspection. Typically, the roadways are very wide (up to 9 m or about 30 ft)

Figure 9 Photograph of Pueblo Bonito (Chaco Canyon) in 1921, prior to major excavations by Neil Judd and the National Geographic Society Salmon Ruins Museum collection.

Figure 11 Map showing extent of the ancient Puebloan society of Chaco Canyon at AD 1100. Modified from map by author, Reed 2004.

Across, and run straight across huge expanses of territory, climbing steep mesas and descending directly into canyons.

Moving beyond the confines of Chaco Canyon proper, we see that the flourishing society centered at Chaco was quite far-flung (Figure 11). Archaeologists are literally finding new Chacoan-affiliated sites, outliers, every few years in increasingly remote areas. Nevertheless, at the present time, perhaps 150 Chaco outliers dating between AD 1050 and 1125 are known. As a group, these sites are similar to those found in Chaco, but are generally smaller in size, have fewer rooms, fewer kivas, many do not meet Chacoan standards for architecture, and most are surrounded by clusters of smaller sites (villages, smaller pueblos, and nonresidential, farming, and other special-use areas). Notable exceptions include the ancient Aztec and Salmon communities in the Middle San Juan region, both of which were as large and well constructed as any great house in Chaco Canyon. Figure 12 Is an historic photograph of Salmon Pueblo, taken by Timothy O’Sullivan in 1874.

In extent, Chacoan outliers are found across four modern American states. Chimney Rock Pueblo lies several miles west of Pagosa Springs, Colorado, and represents the northeastern outpost of Chacoan settlements. Guadalupe Pueblo lies far to the south of Chimney Rock in New Mexico, in the southeastern portion

Figure 12 Historic photograph of Salmon Pueblo in 1874, taken by photographer Timothy O’Sullivan of the Wheeler Expedition. Note the photographer posing in the middle of frame. Salmon Ruins Museum collection.

Of the Chacoan world. Moving across New Mexico to the northwest, the Cottonwood Falls great house in southeast Utah lies near the northwest edge of Chacoan influence. Lastly, Wupatki in northeast Arizona is the westernmost example of a site that shows evidence of Chacoan contact and influence. This far-flung area was larger than New England, and illustrates the vast spread of Chacoan material culture (things like architecture and pottery) and religious-ceremonial influence in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries.

Although they share traits in common with each other, and with great houses in Chaco Canyon, almost every outlier identified thus far has unique characteristics. Thus, understanding the relationship between Chaco Canyon and outlying sites of Chacoan age and affiliation is one of the challenges for Puebloan archaeologists. In fact, the very word itself - outlier - implies a relationship between a center (Chaco Canyon) and a site outside the center (an outlier) that was probably highly variable from site to site. In recent years, Chacoan archaeologists have begun to question these relationships and concentrate more of their research on the outlying sites. This new work has led some to question the existence of an integrated Chacoan ‘system’. In place of an integrated, centrally controlled society, some archaeologists have proposed that the Chacoan world is better described as a confederation of largely independent political entities. Outside Chaco Canyon itself, and an area referred to as the Chaco Core, this is the view adopted here: that the larger Chacoan system was a loose confederation of affiliated but mostly independent Puebloan villages that looked to Chaco Canyon as a religious-ceremonial and economic center.

Pueblo III Period (AD 1150-1300)

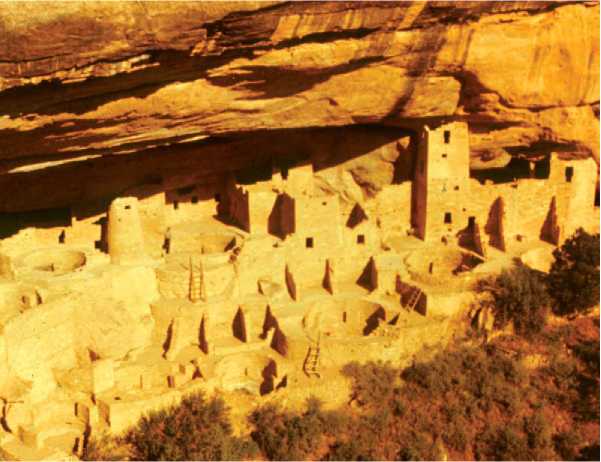

The Pueblo III period (AD 1150-1300) across the northern Southwest is characterized by aggregation, continued production of black-on-white and corrugated ceramics, an increase in the production of polychrome ceramics, continued importance of agriculture, and perhaps minor population decreases throughout the period. During Pueblo III times, most of the Colorado Plateau saw the culmination and termination of its Puebloan occupation. Early in the period, a continuation of the earlier Pueblo II adaptation is apparent. Later, after AD 1250, several new patterns emerged. Population was consolidated and aggregated into fewer and larger sites, and the total number of sites decreased. Defensible locations were occupied in the Kayenta region and elsewhere, and there are indications that warfare was ongoing. Figure 13 Shows Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado.

The collapse of the Chacoan system occurred in Early Pueblo III, by AD 1150. Later in the period (c. AD 1200), many sites experienced a resurgence in population. In the Middle San Juan region, Aztec Ruins and Salmon Ruins reached their peaks in the mid-1200s as local and regional population boomed. The greater Mesa Verde region also reached its zenith during the Late Pueblo III period, by AD 1260. Finally, many other former Chacoan sites, including Chaco Canyon itself, were revitalized with new populations and growth in the mid-late-1200s. The end of the Pueblo III period is marked by widespread abandonment of most areas across the Colorado Plateau (for habitation purposes) and concentration of population into a few areas (e. g., the Hopi mesas and Little

Figure 13 Photograph of large defensible Pueblo III site of Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. Salmon Ruins Museum collection.

Colorado areas in Arizona, the area around Zuni, New Mexico, and the many pueblos located along the Rio Grande and its tributaries in New Mexico).

Pueblo IV and V (post-AD 1300)

During the Later Pueblo IV and V periods, Western Puebloan groups aggregated in a few locations - Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and the Little Colorado River area. The Eastern Pueblo area received many of the people emigrating from the Four Corners region, and large villages grew along the Rio Grande and its tributaries.

Little or no evidence of Pueblo IV or V occupation is present in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Although wandering groups of Puebloans probably made limited use of the area, no permanent occupation of the area occurred until Navajo groups arrived in the AD 1400s.

World History

World History