To understand why the “racial” approach to human variation has been so unproductive and even damaging, we must first understand the race concept in strictly biological terms. In biology, a race is defined as a subspecies, or a population of a species differing geographically, morphologically, or genetically from other populations of the same species.

As straightforward as such a definition may seem, it has three very serious flaws. First, it is arbitrary; there is no agreement on how many differences it takes to make a race. For example, if one researcher emphasizes skin color while another emphasizes blood group differences, they will not classify people in the same way. Ultimately, it is impossible

Fingerprint patterns of loops, whorls, and arches are genetically determined. Grouping people on this basis would place most Europeans, sub-Saharan Africans, and East Asians together as “loops.” Australian Aborigines and the people of Mongolia would be together as “whorls.” The Bushmen of southern African would be grouped as “arches.”

To reach agreement on the number of genes and precisely which ones are the most important for defining races.

The second weakness in the biological definition of race is that no one race has exclusive possession of any particular variant of any gene or genes. In human terms, the frequency of a trait like the type O blood group, for example, may be high in one population and low in another, but it is present in both. In other words, populations are genetically “open,” meaning that genes flow between them. Because populations are genetically open, no fixed racial groups can exist. The only reproductive barriers that exist for humans are the cultural rules some societies impose regarding appropriate mates. As President Obama’s family illustrates (Kenyan father and Euramerican mother, who, incidentally, was an anthropologist), these social barriers are changing.

Third, the biological definition of race does not apply to humans because the differences among individuals and within a so-called racial population are greater than the differences among populations. Evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin demonstrated this through genetic analyses in the 1970s. He compared the amount of genetic variation within populations and among so-called racial types, finding a mere 7 percent of human variation existing among groups.216 Instead, the vast majority of genetic variation exists within groups. As the science writer James Shreeve puts it, “most of what separates me genetically from a typical African or Eskimo also separates me from another average American of European ancestry.”217 This follows from the fact of genetic openness of races; no one race has an exclusive claim to any particular form of a gene or trait.

Considering the above, it is small wonder that most anthropologists have abandoned the race concept as being of utility in understanding human biological variation. Instead, they have found it more productive to study clines—the distribution and significance of single, specific, genetically based characteristics and continuous traits related to adaptation (see Chapter 2). They examine human variation within small breeding populations, the smallest units in which evolutionary change occurs.

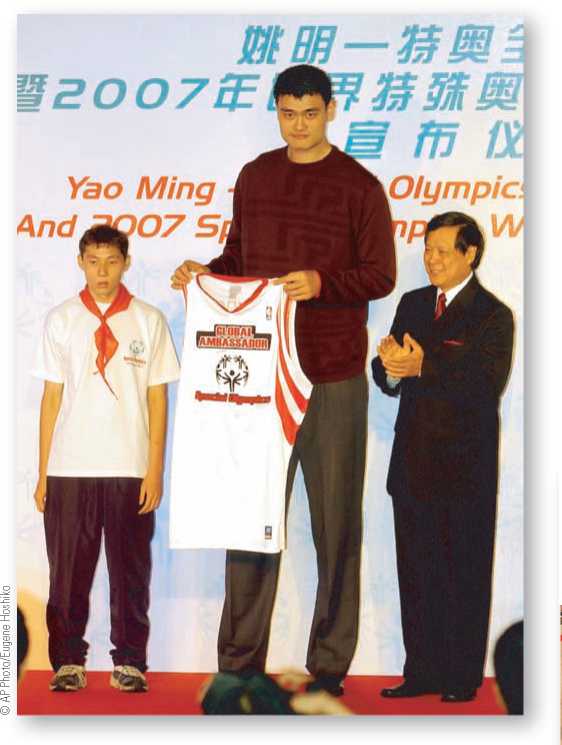

Yao Ming, center for the Houston Rockets, receives his Special Olympics Global Ambassador jersey from athlete Xu Chuang (left) and Special Olympics East Asia President Dicken Yung. Standing side by side, these three individuals illustrate the wide range of variation seen within a single so-called racial category.

World History

World History