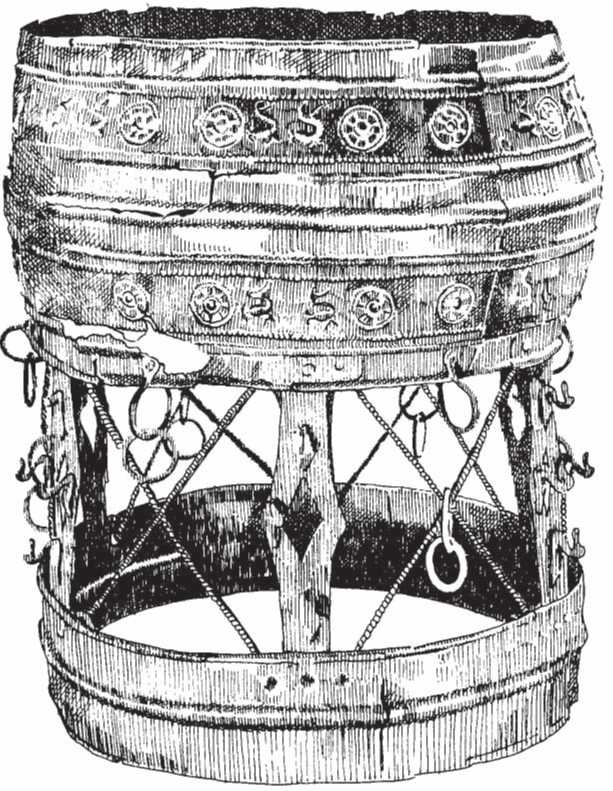

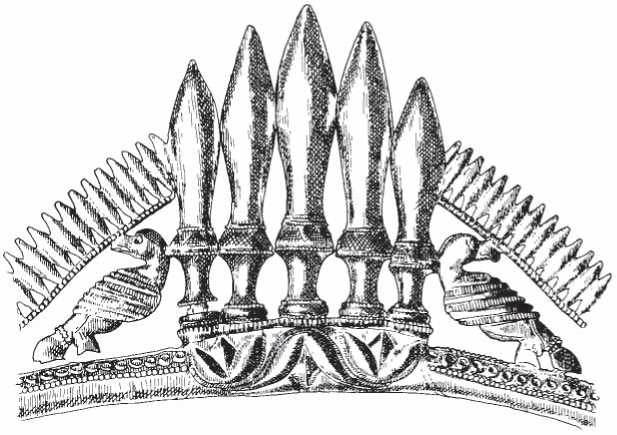

The objects which were made for the preparation and consumption of food and drink frequently bear zoomorphic imagery, and there may well have been specific symbolism associated with such images. An early La Tene example is the pair of drinking-horns from the rich tumulus grave of Kleinaspergle, probably made in the fifth century BC, which terminate in rams' heads. The artists have used these animal heads to indulge their creative fantasies, and have departed from realism in the lines delineating the faces.19 Bronze vessels for mixing wine and flagons for pouring it bear images of the birds and animals familiar to people in daily life. A gold bowl from Altstetten, Zurich, is decorated with images of deer, and the sun and moon;20 a bronze bowl from a burial at Hallstatt21 has a handle in the form of an enchanting group of a cow followed by her calf (figure 2.21). This kind of iconography may have been chosen because of the importance of cattle as units of wealth and currency in a society which relied on its herds for its economic prosperity. Cattle quite often appear as handles for vessels: an example is the realistic bull at Macon in Burgundy. Many Hallstatt vessels were adorned with friezes of horses or horsemen, water-birds and suns (figure 6.8): the Kleinklein bucket-lid (figure 4.3) possesses all these motifs; and there is a close parallel between this iconography and that of an early sixth-century BC belt-plate at Kaltbrunn in Germany, which is decorated with rows of ducks, horses and solar motifs. Water-birds are popular images on repousse ornamented

Figure 6.8 Sheet-bronze vessel-stand decorated in repousse with solar symbols and water-birds, Hallstatt Iron Age, Hallstatt cemetery, Hallstatt, Austria. Height: 32cm. Paul Jenkins.

Vessels, and reflect an earlier Urnfield tradition.22 Their meaning is obscure, but in Bronze Age iconography, they are frequently associated with sun symbols and sometimes form the prow and stern of solar boats. It may be that the water-bird, with its ability both to swim and fly, is an emblem of the two elements of air and water. Late Iron Age bronze vessels sometimes have spouts or handles in the form of animal heads: a bowl of the first century AD from Leg Piekarski in Poland has a spout in the form of a boar;

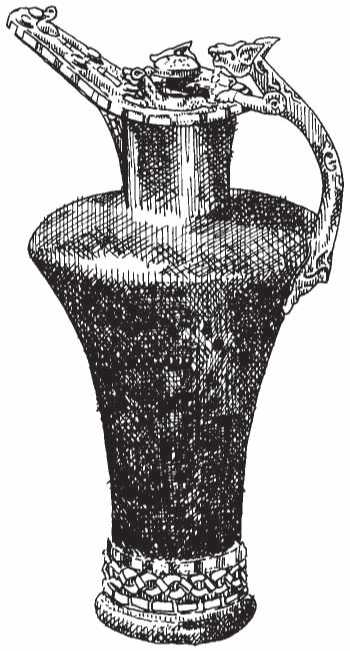

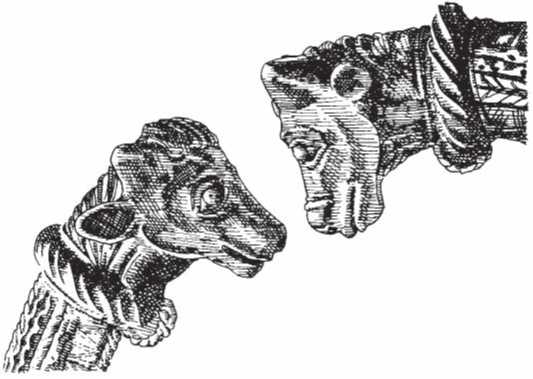

And another bowl from the river Shannon at Keshcarrigan bears the head of a duck as its handle.23 Sometimes creatures that existed only in the imagination were depicted. Flagons or jugs from graves possess handles or lids decorated with beasts that sometimes take weird and wonderful forms: the fourth-century BC princess's grave at Reinheim contained a flagon with a lid bearing the cast figure of an imaginary animal; a similar vessel comes from the chariot-burial of a lady at Waldalgesheim, and here the animal figure standing on the lid is a human-headed horse (these fabulous creatures of the Celtic imagination recur later on Iron Age coins). Two superb late fifth-century or early fourth-century BC bronze flagons from Basse-Yutz (Moselle) (figure 6.9) bear images of dogs on the handles and lids and, swimming along the spouts, are small ducks, 'the simple expression of a neatly observed bit of nature'.24 These vessels are Celtic

Figure 6.9 Bronze wine flagon decorated with wolf or dog and birds, fifth to fourth century BC, Basse-Yutz, Moselle, France. Paul Jenkins.

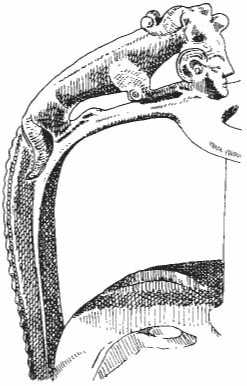

Figure 6.10 Detail of bronze flagon depicting human-headed animal, fifth century BC, from a grave at the Durrnberg, Hallein, Austria. Paul Jenkins.

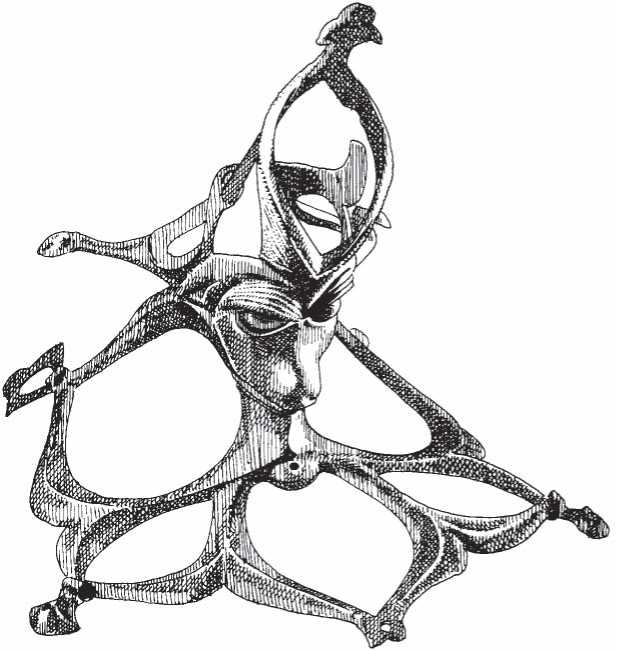

Imitations of Italic beaked flagons, made in a Rhenish workshop. The flagon from a grave at the Durrnberg (Austria), again of fifth-century date, has a human-headed beast as its handle (figure 6.10), and on the rim is a curious creature resembling an ant-eater with a long, trunk-like nose; both animals are decorated with shoulder-spirals.25 Objects interpreted as flagon-mounts from such sites as the third century BC Czechoslovakian cemetery of Malomerice (figure 6.11) are themselves fashioned in the form of beasts and birds: one mount consists of a complex and twisted design centred on an ox's head with great horns; another from the same site takes the form of a bird of prey.

Vessels ornamented with zoomorphic motifs may take the form not just of bronze containers but also of clay pots or wooden buckets with metal fittings. A number of bronze mounts for late Iron Age buckets are in the form of bulls' heads: those from Dinorben and Welshpool in Wales (figure 7.14) and Ham Hill (Som.), are good examples of a common type of escutcheon. The mount from Boughton Aluph (Kent) is in the form of a human head but with jutting bulls' horns.26 Pots used for holding liquid or for cooking food bear animal imagery, often in the form of a frieze around the belly of the vessel. Among the earliest of these are the pots from the seventh-century barrow-group at Sopron in Hungary, which depict scenes from everyday life, including horse-riding (figure 4.10), cattle-herding, cartpulling and hunting.27 A pot at Radovesice in Czechoslovakia had been placed in a hut (perhaps a shrine) in about 400 BC: on the vessel was a frieze of swans, picked out in red paint (figure 7.7). Vincent Megaw28 has

Figure 6.11 Bronze mount in the form of a horned head, third century BC, Malomerice, Czechoslovakia. Height: 18cm. Paul Jenkins.

Suggested that the birds may represent migrating wild swans and that there could be a link between these images and the swans which played such an important role in later Celtic myth (chapter 7). A beautiful long-necked fourth-century BC bottle or flask has engraved ornament on the shoulder, consisting of a range of wild creatures: three hinds, a stag, a hare pursued by a hunting-dog and two boars. The pot comes from a Bavarian cemetery of fifty barrows at Matzhausen (figure 3.3), found in a tomb with a family group of a man, a woman and a child.29 Another grave, at Labatlan, Hungary (figure 3.5), contained a pot with incised and stamped ornament in the form of a graceful, long-bodied deer being attacked by a wolf or dog which sinks its teeth into the neck of its victim. The hide of both animals is represented by circular stamps. The vessel dates to the third or second century BC.30 In the late Iron Age, pots continued to be decorated with animal friezes: the painted pot from Roanne (Haute-Marne) is an example (figure 1.1).

Apart from containers, representations of animal ornament appear on other paraphernalia associated with the consumption of food. The fleshfork from Dunaverney, Co. Antrim in Northern Ireland (figure 2.25) is a rare example of an implement which must have been used to spear boiling meat from a cauldron once it had cooked over the fire. Here, a positive decision was made to decorate a utilitarian object with animal images: all along the length of the fork are freestanding figures of swans and cygnets,31 echoing the water-bird themes of earlier metalwork in Europe. The other important items associated with feasting are iron firedogs, which are frequently ornamented with bull-head terminals. The most spectacular of these is the Capel Garmon firedog from North Wales (figure 5.13), with its magnificent horns and elaborate and fanciful manes. The Capel Garmon find32 was clearly a very precious object: indeed, recent experiments suggest that the complete process of manufacture could have taken as long as three man-years. The firedog was found deliberately buried in a peat-bog lying on its side with a large stone at each end. It was probably a votive gift to the spirit of the sacred pool in which it was deposited. The artist made no attempt to create a realistic image of a bull's head: instead he fashioned a strange, hybrid creature with the horns of a bull but with mane and facial details more suggestive of a horse. Jean-Louis Brunaux33 has put forward a convincing argument for there being a direct association between the imagery of firedogs, with their bulls' or rams' head, and the sacrificial feast in which oxen or sheep were consumed. The function of these firedogs was probably to contain fires,34 rather than for spit-roasting, as has been argued in the past, but even so, their link with feasting is not negated. The recent 'Celts in Wales' exhibition at the National Museum of Wales35 had an impressive reconstruction of a Celtic round house, inside which was a cauldron suspended over a fire, which was guarded by a pair of replicas of the Capel Garmon firedog.

ANIMALS IN PERSONAL ADORNMENT

Jewellery is particularly interesting because it seems likely that certain motifs combined a decorative function with magical or symbolic properties. This is especially true of the zoomorphic iconography which is often incorporated into jewellery design.

Many Iron Age Celtic brooches, which had a genuine function in fastening clothes as well as an ornamental purpose, are in the form of beasts (figure 6.12), which are unrealistic and in some manner fantastic, often being part-man, part-monster or made up of composite animals.

Figure 6.12 Detail of bronze, coral-inlaid brooch, with terminal in the form of a cat's head, mid-fourth century BC, Chynovsky Haj, Czechoslovakia. Length of brooch: 7cm. Paul Jenkins.

This weird supernatural element may well point to the perception of magical, amuletic properties. Most of the surviving brooches come from burials and a very large number consist of bird forms. One very interesting, coral-inlaid brooch from the Reinheim princess's grave is in the form of a hen,36 a newcomer to temperate Europe in Hallstatt times and thought to have been imported from India. Remains of domestic chickens have been found at the Hallstatt stronghold of the Heuneberg in Germany.

Neckrings or torcs, symbols of status and high rank, were worn by the higher echelons of society in life and in death. The animal iconography which is sometimes present may reflect this high status, in addition to possessing magico-divine symbolism. The sixth-century Hallstatt prince buried in a rich wagon-grave at Hochdorf, Germany was interred with a gold neckring decorated with rows of tiny horsemen, as if evoking the dead man's own knightly rank. The bull-head terminals on a late second-century BC silver torc at Trichtingen near Stuttgart (figure 6.13) may again reflect the status and wealth of a nobleman, perhaps the owner of great herds. It is notable that the bulls on the torc are themselves adorned with torcs.37 An early La Tene lady, cremated along with her chariot at Besseringen in Germany, was buried wearing a magnificent gold neck-ornament (figure 6.14) in which two wedge-tailed eagles are depicted as part of the design. The motifs on some arm - and neckrings are sufficiently complicated to suggest the representation of a myth or sacred story: both the gold neckring and an armlet from the grave of the high-born woman at Reinheim bear similar iconography, which includes females whose heads are surmounted by those of a bird of prey with large round eyes and hooked beak (figure 7.17).38 This theme is reminiscent of the Irish myth of the raven-goddesses, the Badbh and the Morrigan, who possessed the ability to change at will from human to bird form. Other possible mythology may be observed in the gold neckrings at Erstfeld in Switzerland: one scene depicts a bull or ox being threatened by a bird with enormous talons.39

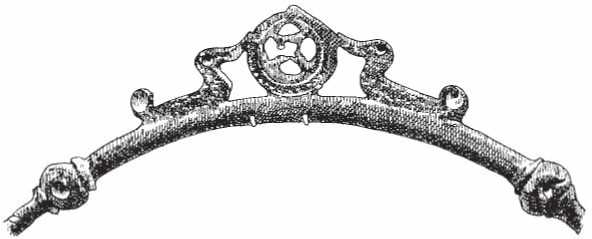

One persistent theme, which can be traced right back to the Urnfield Bronze Age (from around 1300 BC), is that of the sun-wheel and water-bird. We have seen this combined iconography on the vessels, and it is particularly prominent on jewellery. A group of La Tene bronze torcs (figure 6.15) from the Marne region - Catalauni, Pogny and Somme-Taube - consists of plain metal rings with a single group of images comprising a four-spoked wheel flanked by two ducks.40 Pendants, of Hallstatt and later date, carry similar imagery: those from Charroux and Hauterive in France consists of small sun-wheels apparently in boats with a swan or duck at each end.41 These date to the earliest Iron Age, as does the complex pendant at Foret de Moidons (Jura), which is made up of rings, sun symbols and ducks.42 The most attractive ornament of this

Figure 6.13 Terminals of silver torc decorated with bull's heads, second century BC, Trichtingen, Germany. Length of heads: c.6cm. Paul Jenkins.

Figure 6.14 Detail of gold neckring decorated with a pair of eagles, fifth century BC, Besseringen, Germany. Width of detail: c.4cm. Paul Jenkins.

Group comes from a grave at Nemejice in Czechoslovakia, which is in the form of a bronze chain and a miniature wheel, with water-birds perched at the hub and rim, beaks down, as if eating or drinking from a bird-table (figure 7.5).43 There could be religious symbolism here, or the

Figure 6.15 Iron Age bronze torc decorated with wheel and water-birds, Marne, France. Paul Jenkins.

Scene may simply represent a charming vignette from life, the capture in art of a subject witnessed by the artist.

World History

World History