Globalscape

A Global Body Shop?

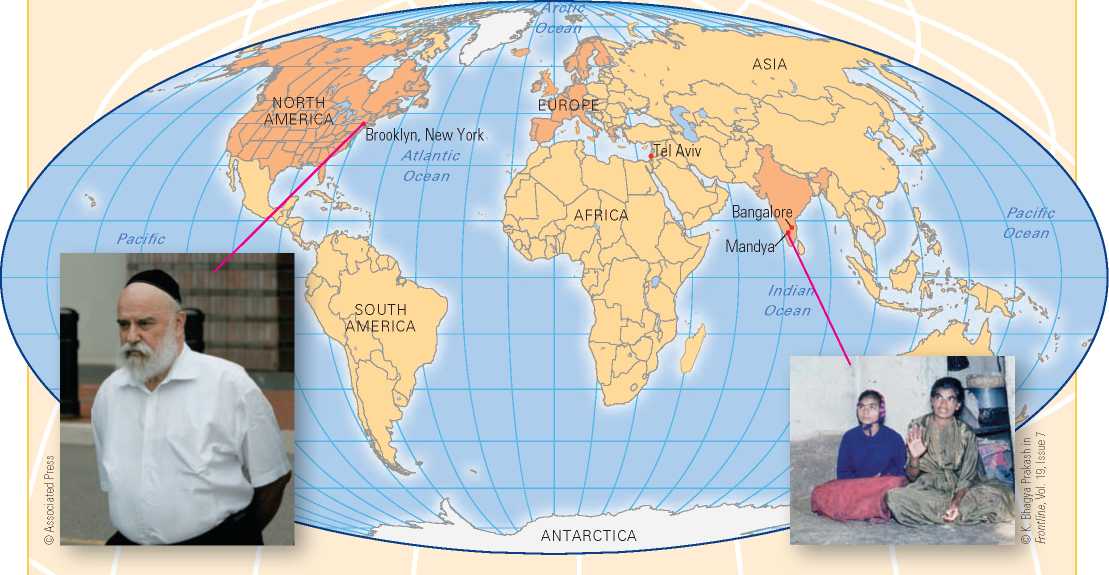

Lakshmamma, a mother in southern India's rural village of Holalu, near Mandya, has sold one of her kidneys for about 30,000 rupees ($650). This is far below the average going rate of $6,000 per kidney in the global organ transplant business. But the broker took his commission, and corrupt officials needed to be paid as well. Although India passed a law in 1994 prohibiting the buying and selling of human organs, the business is booming. In Europe and North America, kidney transplants can cost $200,000 or more, plus the waiting list for donor kidneys is long, and dialysis is expensive. Thus “transplant tourism,” in India and several other countries, caters to affluent patients in search of “fresh” kidneys to be harvested from poor people like Lakshmamma, pictured here with her daughter.

The global trade network in organs has been documented by Israeli filmmaker Nick Rosen, who sold his own kidney for $15,000 through a broker in Tel Aviv to a Brooklyn, New York, dialysis patient. Rosen explained to the physicians at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City that he was donating his kidney altruistically. Medical anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes has taken on the criminal and medical aspects of global organ trafficking for the past twenty years or so. She also co-founded Organs Watch in Berkeley, California, an organization working to stop the illegal traffic in organs.

The well-publicized arrest of Brooklyn-based organ broker Levy Izhak Rosenbaum in July 2009—part of an FBI sting operation that also led to the arrest of forty-three other individuals, including several public officials in New Jersey—represents progress made in combating illegal trafficking of body parts. According to Scheper-Hughes, “Rosenbaum wasn't the tip of an iceberg, but the end of something.”® International crackdowns and changes in local laws are beginning to bring down these illegal global networks.

Global Twister Considering that $650 is a fortune in a poor village like Holalu, does medical globalization benefit or exploit people like Lakshmamma who are looked upon as human commodities? What factors account for the different values placed on the two donated kidneys?

Long-distance exchanges have picked up enormously in recent decades; the Internet, in particular, has greatly expanded information exchange capacities.

The powerful forces driving globalization are technological innovations, cost differences among countries, faster knowledge transfers, and increased trade and financial integration among countries. Touching almost everybody’s life on the planet, globalization is about economics as much as politics, and it changes human relations and ideas as well as our natural environments. Even geographically remote communities are quickly becoming interdependent through globalization.

Doing research in all corners of the world, anthropologists are confronted with the impact of globalization on

Human communities wherever they are located. As participant observers, they describe and try to explain how individuals and organizations respond to the massive changes confronting them. Anthropologists may also find out how local responses sometimes change the global flows directed at them. Dramatically increasing every year, globalization can be a two-edged sword. It may generate economic growth and prosperity, but it also undermines long-established institutions. Generally, globalization has brought significant gains to higher-educated groups in wealthier countries, while doing little to boost developing countries and actually contributing to the erosion of traditional cultures. Upheavals due to globalization are key causes for rising levels of ethnic and religious conflict throughout the world.

Since all of us now live in a global village, we can no longer afford the luxury of ignoring our neighbors, no matter how distant they may seem. In this age of globalization, anthropology may not only provide humanity with useful insights concerning diversity, but it may also assist us in avoiding or overcoming significant problems born of that diversity. In countless social arenas, from schools to businesses to hospitals to emergency centers, anthropologists have done cross-cultural research that makes it possible for educators, businesspeople, doctors, and humanitarians to do their work more effectively.

For example, in the United States today, discrimination based on notions of race continues to be a serious issue affecting economic, political, and social relations. Far from being the biological reality it is supposed to be, anthropologists have shown that the concept of race (and the classification of human groups into higher and lower racial types) emerged in the 18th century as an ideological vehicle for justifying European dominance over Africans and American Indians. In fact, differences of skin color are simply surface adaptations to different climactic zones and have nothing to do with physical or mental capabilities. Indeed, geneticists find far more biologic variation within any given human population than among them. In short, human “races” are divisive categories based on prejudice, false ideas of differences, and erroneous notions of the superiority of one’s own group. Given the importance of this issue, race and other aspects of biologic variation will be discussed further in upcoming sections of the text.

A second example of the impact of globalization involves the issue of same-sex marriage. In 1989, Denmark became the first country to enact a comprehensive set of legal protections for same-sex couples, known as the Registered Partnership Act. At this writing, more than a half-dozen other countries and a growing number of individual U. S. states have passed similar laws, variously named, and numerous countries around the world are considering or have passed legislation providing people in homosexual unions the benefits and protections afforded by marriage.11 In some societies—including Belgium, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Spain, and Sweden—same-sex marriages are considered socially acceptable and allowed by law, even though opposite-sex marriages are far more common. The same is true for several U. S. states including Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

As individuals, countries, and states struggle to define the boundaries of legal protections they will grant to same-sex couples, the anthropological perspective on marriage is useful. Anthropologists have documented same-sex marriages in human societies in various parts of the world, where they are regarded as acceptable under appropriate circumstances. Homosexual behavior occurs in the animal world just as it does among humans.13 14 The key difference between people and other animals is that human societies possess beliefs regarding homosexual behavior, just as they do for heterosexual behavior. An understanding of global variation in marriage patterns and sexual behavior does not dictate that one pattern is more right than another. It simply illustrates that all human societies define the boundaries for social relationships.

A final example relates to the common confusion of nation with state. Anthropology makes an important distinction between these two: States are politically organized territories that are internationally recognized, whereas nations are socially organized bodies of people who share ethnicity—a common origin, language, and cultural heritage. For example, the Kurds constitute a nation, but their homeland is divided among several states: Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. The international boundaries among these states were drawn up after World War I, with little regard for the region’s ethnic groups or nations. Similar processes have taken place throughout the world, especially in Asia and Africa, often making political conditions in these countries inherently unstable. As we will see in later chapters, states and nations rarely coincide—nations being split among different states, and states typically being controlled by members of one nation who commonly use their control to gain access to the land, resources, and labor of other nationalities within the state. Most of the armed conflicts in the world today, such as the manylayered conflicts in the Caucasus Mountains of Russia’s southern borderlands, are of this sort and are not mere acts of “tribalism” or “terrorism,” as commonly asserted.

As these examples show, ignorance about other cultures and their ways is a cause of serious problems throughout the world, especially now that our interactions and interdependence have been transformed by global information exchange and transportation advances. Anthropology offers a way of looking at and understanding the world’s peoples—insights that are nothing less than basic skills for survival in this age of globalization.

1. Anthropology uses a holistic approach to explain all aspects of human beliefs, behavior, and biology. How might anthropology challenge your personal perspective on the following questions: Where did we come from? Why do we act in certain ways? Does the example of legalized paid surrogacy, featured in the chapter opener, challenge your worldview?

2. From the holistic anthropological perspective, humans have one leg in culture and the other in nature. Are there examples from your life that illustrate the interconnectedness of human biology and culture?

3. Globalization can be described as a two-edged sword. How does it foster growth and destruction simultaneously?

4. The textbook definitions of state and nation are based on scientific distinctions between both organizational types. However, this distinction is commonly lost in everyday language. Consider, for instance, the names United States of America and United Nations. How does confusing the terms contribute to political conflict?

5. The Biocultural Connection in this chapter contrasts different cultural perspectives on brain death, while the Original Study features a discussion about traditional Zulu healers and their role in dealing with AIDS victims. What do these two accounts suggest about the role of applied anthropology in dealing with cross-cultural health issues around the world?

Bonvillain, N. (2007). Language, culture, and communication: The meaning of messages (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

An up-to-date text on language and communication in a cultural context.

Fagan, B. M. (2005). Archaeology: A brief introduction (9th ed.). New York: Longman.

This primer offers an overview of archaeological theory and methodology, from field survey techniques to excavation to analysis of materials.

Kedia, S., & Van Willigen, J. (2005). Applied anthropology: Domains of application. New York: Praeger.

Compelling essays by prominent scholars on the potential, accomplishments, and methods of applied anthropology in domains including development, agriculture, environment, health and medicine, nutrition, population displacement and resettlement, business and industry, education, and aging. The contributors show how anthropology can be used to address today’s social, economic, health, and technical challenges.

Marks, J. (2009). Why I am not a scientist: Anthropology and modern knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press. With his inimitable wit and deep philosophical insights, biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks shows the immense power of bringing an anthropological perspective to the culture of science.

Peacock, J. L. (2002). The anthropological lens: Harsh light, soft focus (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. This lively and innovative book gives the reader a good understanding of the diversity of activities undertaken by cultural anthropologists, while at the same time identifying the unifying themes that hold the discipline together. Additions to the second edition include such topics as globalization, gender, and postmodernism.

Challenge Issue The genetics revolution has given new meaning to human identity. Police identify criminals through DNA fingerprinting and maintain DNA databases of convicts and suspects for solving crimes in the future. Others wrongfully imprisoned for many years have been freed after genetic testing. But the thornier issue in genetics is whether genes can predispose an individual to criminal behavior. Do our genes determine our actions? Some scientists argue that biology controls behavior because of hints found in the genome, the complete sequence of human DNA. These new theories are dangerously similar to those proposed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as they do not take into account the social and political environments in which genes are ultimately expressed. As we learn more about the human genetic code, will we reshape our understanding of what it means to be human? How much of our lives are dictated by the structure of DNA? And what will be the social consequences of depicting people as beings programmed by their DNA? Individuals and societies can answer these challenging questions using an anthropological perspective, which emphasizes the connections between human biology and culture.

© Imagemore Co., Ltd./Corbis

World History

World History