Preliminary remarks

Our landscape, in Quammen’s sense, is the scene of Ice Age Siberia. Remote in both the realms of time and space, Siberia is an area larger than the United States or Australia. Our curiosity takes us to open and cave sites east and south of Lake Baikal, along the Yenisei and Ob rivers, and into limestone karst caves located in the Altai Mountains near Mongolia. In this territory, marvelously well-preserved faunal remains have been found by Russian archaeologists, paleontologists, and speleologists. We focus on the human and non-human inhabitants of 30 sites. In particular, we are interested in the perimortem taphonomy of late Pleistocene humans and cave hyenas (Crocuta speiaea), apparently a sub-species of the African spotted hyena.

Analogy and taphonomy

“The taphonomic approach is most creative when ancient archaeological patterns are analyzed and interpreted in relation to modern analogs in which relevant cause and effect relationships are known from direct observations” (Bunn 1991:435).

The archaeological record of Ice Age northern hunters, fishermen, and gatherers is almost invisible when compared with, say, the Siberian ethnographic items illustrated by Fitzhugh and Crowell (1988). Our sites contain no perishable items. Artifacts are almost all made of stone. Nevertheless, we believe that we have learned some rare and quiet lessons during our study of ancient bone damage.

This book contains two linked stories. The main story deals with perimortem taphonomy, the study of damage done to bones at or near the time of death of the creatures in question. Illustrations of damage types and variations on this story are in Chapters 2-4.

Most of the assemblages we examined are of late Pleistocene age. The main exception is a Pacific coastal Holocene site that was added so that our study could include an

Approximation of the Siberian Far East oceanic coastal habitat that was flooded due to rising sea levels at the end of the Pleistocene.

The second - and much shorter - story is illustrated in various figures and told in their captions, which include the activities that led up to our collaborative personal odyssey of travel and study from 1998 to 2006, the years we collected our taphonomic observations (Figs. 1.1-1.25 and elsewhere). This story hopefully will help readers unfamiliar with Siberia to better understand the context and landscape within which our work was carried out.

How this study began

The senior author first met the other team members of this project, Nicolai D. Ovodov and Olga V. Pavlova, on a very cold and gray Siberian day in January 1984. Accompanied by his youngest and anthropologically trained daughter, Korri Dee, we had traveled to Novosibirsk to examine prehistoric human dental remains in the collections of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (formerly the IHPP), Academgorodok (which means “Academy City”). It is called so because this unique Russian government enterprise has thousands of scientists studying the natural and human cultural world of Siberia in numerous specialized institutes. The dental studies, mentioned above, were permitted by Institute Director and paleoarchaeologist, Academician Anatoly P. Derevianko, seeking to add information for a long-term study on the origin and dispersal of anatomically modern humans, particularly Native Americans (Turner 1992a, 1998, and elsewhere). Olga Pavlova had been assigned to help us with translations. She was a soft-spoken, petite woman with marvelous skills in English and Russian languages.

Our first meeting with Nicolai was in his cold little attic-level fourth-floor lab, which was down a long, dark, unheated hallway from the lab space provided for our three-week study of Siberian Holocene human teeth. Nicolai was a friendly, hospitable person, then 45 years old. He had no pretensions, and was highly knowledgeable about mammalian osteology and the Pleistocene fauna whose remains filled up all the shelves in his cramped lab. On the highest shelf sat a silver samovar and an Ice Age wooly rhinoceros skull - symbols of where much of our future team’s remaining careers would be focused. Most of the faunal remains collected during 40 years of archaeological and related paleontological research were kept in a large attic storeroom, collections that began to accumulate with the many excavations led by the Institute’s first director, Academician A. P. Okladnikov.

The landscape

Most mammalian life plays out on the ground surface of the planet, and its non-uniform landscape selects for organic variation best suited for specific conditions. The landscape of Siberia can be roughly divided into three great geographic provinces: a vast western plain, possibly the largest plain in the world; a rumpled mineral-rich hilly and

Map of Siberian site locations.

Fig. 1.2 Odyssey. Khabarovsk mammoth. A life-size replica of a Pleistocene wooly mammoth, specially erected outside the Sport and Science Museum, Amur Blvd., Khabarovsk, symbolized the unique Siberian venue for the 1979 Pacific Science Conference. It was at this conference that the senior author met Russian researchers who would in time come to be close friends. Although he and the junior author, Olga Pavlova, did not actually meet face-to-face, years later, when looking back at photos he had taken at the conference, he discovered that he had taken available-light color photos of Ruslan Vasilievsky and later, Robert Ackerman, with Pavlova translating for both presenters in a large lecture hall. Pavlova recalls Turner’s presentation and the laudatory remarks made afterwards by Russia’s most brilliant anthropologist and a speaker of nine languages, Sergey Arutyunov, chairman of the Caucasus section, Institute of Ethnography, Moscow.

This gathering of Pacific Rim scientists was at a tense time between the Soviet Union and the West. Nevertheless, the conference venue, far from Moscow, made it possible for Soviet and Western scholars to exchange information and ideas more-or-less openly, particularly about future research collaboration. Hence, the senior author made plans for future research in the Soviet Union with the help of Sergey Arutyunov, Ruslan Vasilievsky, and apparently with the approval of Academician A. P. Okladnikov, who attended the conference aided by his archaeologist-translator, Alexander Konopatsky. Okladnikov would months later send his famous book on the prehistoric art of the Amur to the senior author (CGT color Khabarovsk 8-23-79:3).

Mountainous region in the eastern half; and a high mountainous southern region bordering on Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan. Siberia possesses some of the world’s largest rivers, notably the Ob in the west, and the Yenisei, Lena, and Amur in the east. Into these rivers, and others like them, drain hundreds of smaller rivers. Most of the

Fig. 1.3 Odyssey. February in Novosibirsk. The two women who helped get the work started for this book.

The senior author began data collection in Siberia in February 1984, aided by his daughter Korri Dee, shown on the left with Olga Pavlova. The temperature was -29°C (-20.2°F) at the time the photograph was taken. The pair are standing at the entrance to the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology (then called the Institute of History, Philosophy and Philology). The flags barely visible in the upper right corner were commemorating the death of Yuri Andropov. Korri and the senior author learned ofhis death 48 hours before it was announced to the Soviet public because they had heard the news in a BBC broadcast they picked up on the small shortwave radio they carried with them to Siberia. It was during this visit that we were shown faunal specimens in Ovodov’s lab and that the seed was planted for research that would culminate in this book (CGT color IHPP 2-14-84:19).

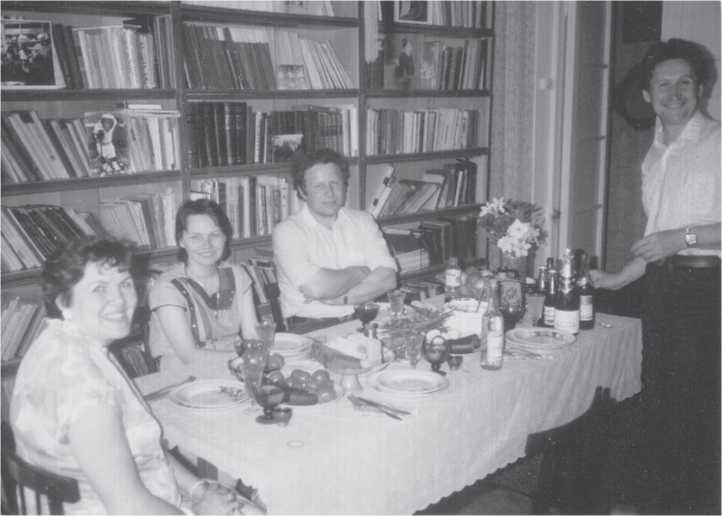

Fig. 1.4 Odyssey. A private dinner. A Friday evening dinner party at the Academgorodok apartment of Academician Anatoly P. Derevianko (right) and his then wife, physical anthropologist Tatiana Chickisheva (second from left). Archaeologist Alexander Konopatsky (center) served as translator for the gathering. The senior author’s late wife, Jacqueline, is at the left. It was this gathering that led to the Turners’ trip to the Altai and, subsequently, the clandestine Moscow examination of Mousterian teeth found in two of the Altai cave sites (at that time it was illegal for foreigners to study and publish on Soviet materials before Russian scholars) (CGT color Academgorodok 5-29-87:7).

Greatest rivers originate in the general region of the third and mountainous area, which we will refer to hereafter as simply the Altai. With the exception of the Amur and other smaller eastern rivers, the great rivers of Siberia flow northward, providing natural but long looping routes to the Arctic seas. In the spring, summer, and fall these waterways can be followed by boats, and in the winter by foot, sled, or pack animals on the thickly frozen surfaces. Lakes abound in Siberia, the greatest of all being Lake Baikal, whose single outlet, the Angara River, runs through the old Siberian city of Irkutsk founded by Russian promyshleniki (fur hunters) in 1651.

Today, the vegetative zones in the area encompassed by our study in southern Siberia, extending from the Ob River in the west to Primorsky Territory along the Sea of Japan in the east, are characterized as forest, steppe, meadow, alpine tundra, or varying combinations of these plant communities. In mixed zones, the first word in a hyphenated combination indicates the dominant vegetation. For example, if there is more steppe than forest, then the region would be termed steppe-forest. Steppe includes drought-resistant

Fig. 1.5 Odyssey. Flight into the Altai. Jacqueline Turner (right), Olga Pavlova, the senior author, and about 20 other passengers flew from the old mining city of Barnaul to the Altai farming village and “county administrative center” of Soloneshnaya in the single-engine biplane visible in the background. These aircraft were known to Russians as “corn” planes because they could land almost anywhere. From there, a bottomless muddy mountain road was cautiously navigated by the driver, Volodya Tekunov (left), all afternoon to the archaeological field camp at Denisova Cave (CGT color Soloneshnaya 6-9-87:21).

Plants and small animals, even lizards, and vast tracts of tough, drought-resistant grass. The steppe is a key plant zone for the initial colonization of the New World. Pollen, soil, and faunal studies indicate that, other than temperature and seasonal duration, the late Pleistocene environmental influence on humans in southern Siberia was not vastly different from what it is today. Forested regions in the past, as now, tended to be higher, colder, better watered, and more mountainous than the steppe country. Drainage affected the type of forest vegetation. Over the course of many millennia in the late Pleistocene, climate fluctuated so that today’s plant zones shifted slightly in latitude and elevation in accompaniment with changes in temperature, albedo (ground surface reflectivity), and precipitation. Vast steppe grasslands and steppe-forest existed and supported herds of bison, horses, and other hoofed animals. Skeletal remains of various deer and other browsers, along with habitat-specific rodents and insects, indicate the existence of the forest condition, as do the occasional bones of beaver and other species dependent on a forested habitat. Small animal bones in owl pellets provide a remarkable source of information about the habitat surrounding ancient nesting sites. The relatively large number of remains of top-feeders such as cave hyenas, cave lions, wolves, and other

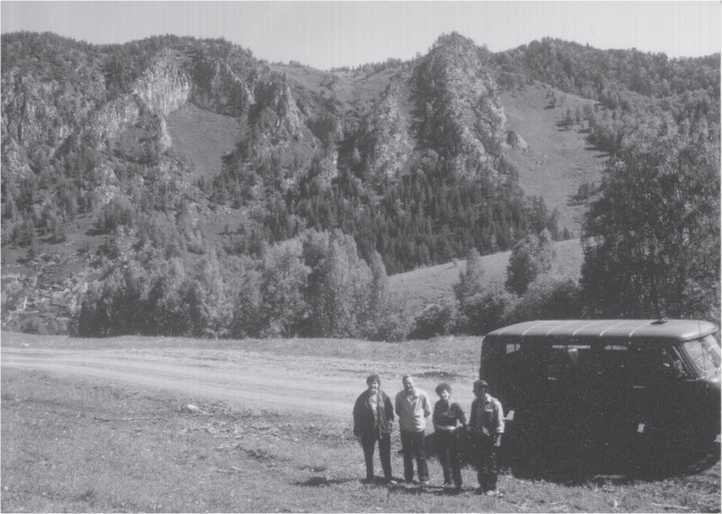

Fig. 1.6 Odyssey. On the way to Denisova Cave. A photo stop in the forest-covered steep limestone

Altai Mountains. We traveled along a winding route fTom Soloneshnaya to Denisova camp. The route paralleled the rushing Annui River, and passed through two small, poor villages settled in small relatively open mountain valleys. Livelihood was based mainly on milk production. Not far from this location, in later years a very deep lower Middle Paleolithic open site called Kamara was discovered. Left to right: Jacqueline Turner, Vyacheslav Ivanovich Molodin, Olga Pavlova, and driver (CGT color Altai 6-9-87:22).

Large carnivorous predators speak to the large number of prey upon which they fed. Exactly why many of the megafauna, including mammoth and rhinoceros, went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene remains an unresolved question in Ice Age biological history. During the course of our multi-year study, we thought possibly that we could help answer the megafauna extinction question, and to some extent we may have. We have assembled bits and pieces of diverse information that hint at a significant human contribution, even though climate and habitat changes patently occurred in Siberia as elsewhere in the world. English-speaking readers wanting more details about the late Pleistocene northland landscape will find R. D. Guthrie (1990), J. F. Hoffecker (2005), N. Ukralutseva, L. Agenbroad, and J. Mead (1996), H. K. Vereschagin and G. F. Baryshinkov (1984), and F. H. West (1996) helpful.

Studying perimortem taphonomy

The concept of, and term, taphonomy were coined by the Russian paleontologist, Ivan Antonovich Yefremov (1940), whose base of operations was the Institute of

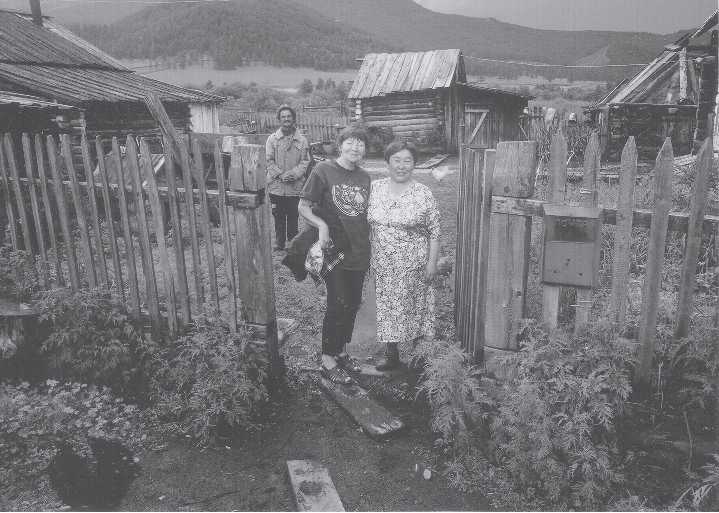

Fig. 1.7 Odyssey. Native-style residence. Shown is the entrance to the Karakol village property of a retired teacher, Galina Erosiva (right). At left is Olga Pavlova, and in the background is a developmentally disabled villager who helps Erosiva and others with simple tasks such as hauling water. This home is like the strictly Russian village homes and out-buildings, but differs in also having a round, cribbed, hogan-like native Altai structure. Out of sight in the distant mountains is the Paleolithic Kaminnaya Cave site (CGT color Karakol 7-10-99:34).

Paleontology in outer Moscow (Figs. 1.22-1.24). He defined taphonomy to mean the study of the “burial” of plants and animals, their geological placement, and all agencies, associations, changes, and damage to the organisms that were involved in the “processes of embedding” into the lithosphere. Although Yefremov did not specifically mention humans as an agency of embedding (he was clearly concerned with very ancient life), it is clear that he meant all possible agencies. One of the near-universal characteristics of human culture is the burial of our dead, at least family and friends. This alone makes us an element in his definition of taphonomy.

While some workers look upon taphonomy as little more than a destructive or information-destroying process, we believe that there is often much useful information about how a bone or shell accumulation and its damage occurred, as well as a number of related considerations. We are far from alone in this view. For example, see Brain (1981), Lyman (1994), Grupe (2007), and many others we will cite in the course of this book.

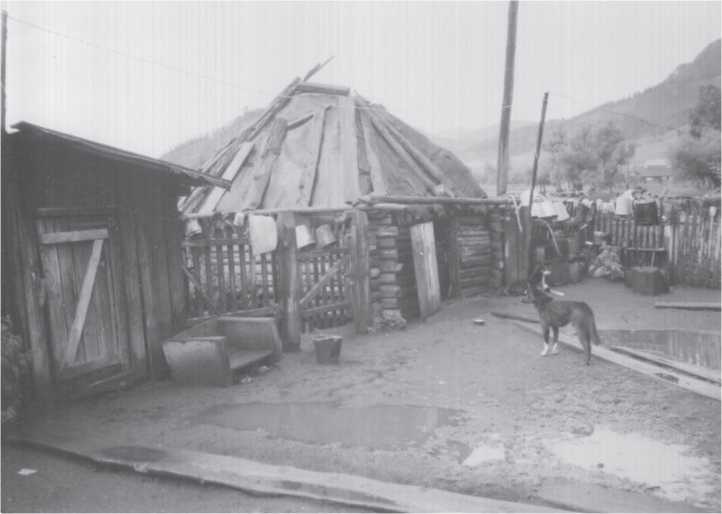

Fig. 1.8 Odyssey. A Karakol village round house. Galina Erosiva’s windowless log round house (aiyel) is 40 years old. It stands in the 200-person village (500 before World War II) whose cash economy is based mainly on raising wild deer for antler export to China. Both Altai and Navajo cribbed round houses of the American Southwest face eastward. An Altai native man must build an aiyel for his bride-to-be before the marriage can take place. He will also construct a rectangular Russian-style windowed log house (CGT neg. Karakol 7-10-99:00).

The boundary between destructive taphonomy and damage-producing information such as tooth marks is not easy to define, especially in deep time (Plummer 2004). It is our explicit theoretical view that all damage is information. The problem is determining what the damage means. This is especially true when working with museum collections that generally have little contextual information.

We chose Siberia to carry out this research for both scientific and personal reasons. One of the scientific reasons was the hope that, in Quammen’s sense, we might help understand why the colonization of the New World from Siberia was so late in relation to the much earlier colonization of most of the rest of the world. Another was curiosity about bone damage that was ignited by the senior author’s research on prehistoric cannibalism in the American Southwest and Mesoamerica. The personal reasons were many, not the least of which was the feeling of true adventure wherever we traveled, with every assemblage we studied, and with everyone whom we met in the field, in museums and institutes, and at conferences (Fig. 1.25). The following allegorical story abbreviates the scientific evidence and inferences in this book.

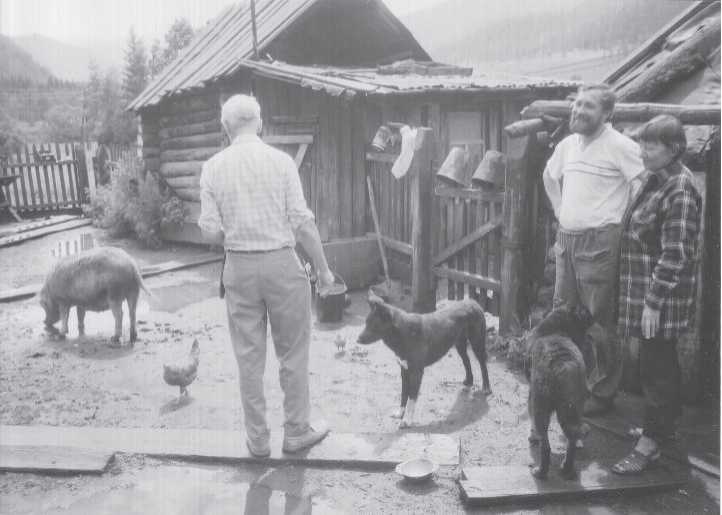

Fig. 1.9 Odyssey. In an Altai village yard. After a thunderous afternoon rain and hail storm, Nicolai Ovodov (left), Sergei V. Markin (middle), Olga Pavlova (right), a sow, chickens, ducks, and dogs emerge from cover (CGT neg. Karakol 7-10-99:24).

World History

World History