The social and economic changes that occurred during the Early and Middle Holocene are most clearly documented in the archaeological records of the tropical lowlands of western Ecuador, northern Colombia, and in the Santa Maria valley of Panama. In all three regions, a broad range of food resources was being exploited, from both land and sea, but through time there was greater concentration on

Particular resources - especially calorie-rich plant foods. At the same time, it is evident that territoriality was important, as well as community solidarity.

The people of the Las Vegas culture (c. 10 500 to 6500 years ago), established a centrally located ‘base camp’ on the Santa Elena Peninsula of Ecuador. The camp was strategically located near water, in what was a seasonally dry landscape, and near areas of enriched plant growth. From that camp, individuals or small foraging groups could set out to exploit various resource patches that were mostly within less than a day’s hike from the camp. Mangrove lagoons, rocky sea cliffs, sandy beaches, hunting areas, and seasonally productive seed, berry, fruit and root localities were within range. Exploitation of these resources is attested by the remnants of small ‘lunchtime’ or overnight camps that were apparently visited repeatedly by the human groups. During the dry season, it is likely that groups of foragers trekked deeper into the interior valleys, but the archaeological evidence of those journeys has not yet been discovered. By 8000 years ago, the phytolithic record indicates that maize had been added to the inventory of plants cultivated by the Las Vegans. Grinding stones were used for processing some foods, but food storage containers have not survived in the archaeological record.

The base camp of the Las Vegans not only served as a logistic depot for the foraging groups but also as sanctified ground that represented the existence and continuity of their society. Nearly 200 skeletons were excavated from the site, most of them apparently buried beneath the floors of small huts. Funerary rites, at least, and probably other periodic and/or seasonal rituals were carried out at the site, some rites probably drawing together all members of the community and reaffirming their common heritage. Such solidarity would have become increasingly important as population density increased, which would have intensified competition for resources, in turn requiring defense of territorial boundaries.

In Panama, a similar scenario was unfolding. About 7000 years ago, a camp was founded at the site of Cerro Mangote, which was situated near the Pacific shore. Because of the abundance of mollusk shells in the midden, the site was initially interpreted as a shellfish-collecting camp, but subsequent more detailed investigations have revealed that at least half of the foods consumed at the site were from plants and game collected and hunted from the terrestrial environment. Contemporary sites and small encampments have now been identified in nearby caves and more distant hills to the east. The sites in the hills have been linked to progressive deforestation of the region, resulting from successive small-scale fires believed to have been set by humans wishing to expand game grazing areas and/or practicing slash-and-burn agriculture. The latter inference is based on the discovery of microbotanical remains of maize, arrowroot, and other domesticated plants extracted from grinding stones that archaeologists have excavated from the cave sites. Many human burials have been excavated at Cerro Mangote, and the chemical analysis of their bones indicates that their diet was composed partly of maize.

The economic picture in Panama, then, during the Early to Middle Holocene, is one in which human groups were highly mobile, ranging over a considerable territory, exploiting a wide range of resources from sea and land, and at some point beginning to incorporate domesticated plants into their food base. Cerro Mangote may have been a base camp from which daily treks were made to nearby resource hot spots, but the nearby temporary campsites are not as evident as those associated with Las Vegas in Ecuador. The concentration of human burials, however, suggests that Cerro Mangote was consecrated as a place of the ancestors and that, although its community members trekked over a wide area in pursuit of food, they gathered together to venerate and bury their dead and to reaffirm their common heritage.

In Colombia, the most detailed record for this segment of time comes from the San Jacinto hills and the alluvial plains of the lower Magdalena River Valley. This is a large area extending from the Caribbean coast to the savannas 180 km inland, an area that probably encompassed the territory of more than one social group. The excavated record begins in the hills at the site known as San Jacinto 1. Recorded in the stratigraphy of San Jacinto 1 are a series of seasonal occupations ranging in time from c. 6000 to 5300 years ago (Figure 2). The excellent preservation and clear delineation of each stratum is unique for sites of comparable age from the Neotropical lowlands. The site was situated on the point bar of a small stream and was occupied during the dry season; annual floods buried the occupation debris. The salient features of the site are shallow pits that were renewed with each occupation. The linings of the pits were burnt, and many of the pits were associated with fire-cracked stones and carbonized plant residues. An abundance of wild grass seeds was recovered from the carbonized remains, but as yet no domesticated species have been conclusively identified. The broken remains of ceramic vessels and grinding stones were also found in significant numbers.

The function of San Jacinto 1 clearly differs from that of Cerro Mangote or the main site of the Las Vegas culture. All the evidence points to it having been a seasonal camp, occupied annually for the

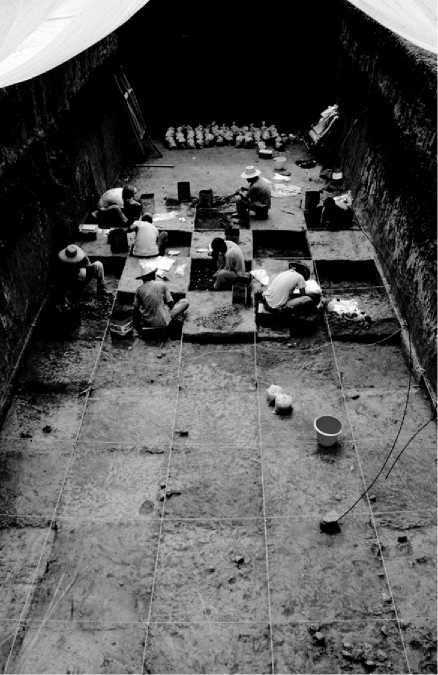

Figure 2 Excavations at San Jacinto 1, Colombia. (Photo by Augusto Oyuela-Caycedo)

Purpose of harvesting, processing, and possibly storing wild plants, particularly wild grass seeds that grew on the point bar. Heated rocks were used in the pits to steam the grass seeds. With the exception of the Taperinha pottery of the Central Amazon, the San Jacinto ceramics are the oldest yet discovered in the Americas. The ceramic vessels show no evidence of having been used for cooking; rather the large jars were probably used to detoxify, ferment, and/or store the seeds after processing. A high percentage of the vessels is elaborately decorated with incised, excised, and modeled motifs, indicating that pottery played a social-symbolic role (see Image and Symbol; Pottery Analysis: Stylistic); the vessels were likely used in feasting and rituals that accompanied the harvest (Figure 3).

No base camp or network of temporary camps has yet been found contemporary with San Jacinto 1. Within less than 1000 years, however, San Jacinto 2, which may qualify as a base camp, but is as yet unexcavated, and a number of other sites were established in the region, some near the coast, associated with wetland environments. The distinctive ceramic

Figure 3 A ceramica adorno in the shape of a bird head from San Jacinto 1. The fabric of the pottery is fiber-tempered. (Photo by Vic Krantz)

Style of San Jacinto continued. Vessels were manufactured, in greater quantities and with still more elaborate motifs. The people of the wetland sites focused on shellfish, turtles, and other local resources. No domesticated plants or other evidence of agriculture have yet been found in association with these sites, but it is plausible, given the record from Panama, that they were linked with as yet undiscovered farming communities situated in the San Jacinto Hills. Puerto Hormiga, the best known of these sites, was organized in a doughnut shape, with a central cleared area with household garbage around the periphery. Other sites of the same period, including San Jacinto 2, show evidence of similar planning, suggesting that settlements were organized according to a culturally determined pattern. Whether or not there were permanent villages at that time (c. 5000 years ago) in northern Colombia, however, remains to be investigated.

World History

World History