Without any doubt Rommel had a talent for appreciating the situation quickly and reacting accordingly. The way he dealt with the situation he and his company, 9./IR 124, had to face on 29 January 1915 clearly shows how the young Rommel did not differ greatly from the older, experienced one. At first the attack seemed simple; the company, moving to the left of the neighbouring III Bataillon, quickly seized three series of French defensive lines without problems, largely because the French were withdrawing. After advancing for 1.5km (1 mile), Rommel and his men found another French fortified position, heavily protected by wire entanglements. This time, seeing his men reluctant to follow him, Rommel was forced into desperate measures. He got hold of his leading platoon commander and simply told him 'obey my orders instantly or I'll shoot you'. This worked and the company was soon inside four French blockhouses, with the wire to their backs. At this point, the French started to fire at them from the flanks while a large force started to attack 9. Kompanie's positions; Rommel requested for support, but this was not forthcoming and the company was surrounded and forced to withdraw. As Rommel recorded, he faced three options: fight to the last

Round and then surrender, try and make his way back through the wire,

Leading from the front was a key part of Rommel's concept of command throughout his entire career. Here he is checking maps with officers from 7. Panzer-Division during the early stages of the German attack in the West in May 1940. (NARA)

Which almost certainly meant heavy losses, or attack. And attack he did, spreading confusion and disorder among the French who, once their lines had been ruptured, proved unable to keep up with the fast pace of Rommel's company. Eventually, they managed to get through the French defensive lines, cut a passage through the barbed wire and rejoin the rest of II Bataillon for the cost of five wounded. Rommel's comment was that it was unfortunate that no one had been able to exploit his company's success.

Although Rommel may appear to have taken a gamble, he would not have seen it that way. German officers were trained to evaluate the situation and react swiftly taking the enemy by surprise, not to gamble. Years later, writing about the war in North Africa, Rommel pointed out the difference:

It is my experience that bold decisions give the best promise of success. But one must differentiate between strategical and tactical boldness and a military gamble. A bold operation is one in which success is not a certainty but which in case of failure leaves one with sufficient forces in hand to cope with whatever situation may arise. A gamble, on the other hand, is an operation which can lead either to victory or to the complete destruction of one's force. Situations can arise where even a gamble may be justified - as, for instance, when in the normal course of events defeat is merely a matter of time, when the gaining of time is therefore pointless and the only chance lies in an operation of great risk.

The Rommel Papers, p. 201

Rommel was a bold commander, not a gambler. The battle for the Kolovrat Ridge and the advance that followed are perfect examples of Rommel's application of his battlefield talents, and it must rank as one of his finest achievements as a field commander. Again, Rommel appreciated the situation at first hand, driving himself and his men over difficult terrain in the face of the enemy, making bold decisions and overcoming all obstacles.

A few days after the Kolovrat Ridge, Rommel experienced the changing nature of warfare in an episode that was to shape his future career. On

7 November, he led his men forwards to attack an Italian position on a mountain pass from which they were firing against the advancing German columns. He took three rifle and one machine-gun companies up the mountain by a circuitous route. The rifle companies were supposed to launch the attack while the machine guns provided covering fire. However, Rommel spent too long with the machine-gun company setting up their fields of fire and was late in joining his rifle companies. Although the machine guns were providing covering fire, the attacking force waited for Rommel to join them and, by the time the attack was launched, the covering fire had died away. Rommel's subordinates had failed to live up to the high standards that he set both for himself and for them. This led him to a simple conclusion: if he wanted to be sure of success he needed to keep everything under his personal control.

Owing in part to this, Rommel's relationships with his subordinates could often be difficult. From the moment he joined the 7. Panzer-Division in February 1940, he complained about his officers who preferred an 'easy life,' describing some of them as 'floppy'. Less than two weeks after his arrival, Rommel had a clash with a battalion commander who was forced to leave the very same day to set an example for the others. Things were also not easy in North Africa, and it was only 'Later in the campaign, when I had had a chance to establish closer relations with the troops', that he discovered how 'they were capable at all times of achieving what I demanded of them' (The Rommel Papers, p. 119). As was Rommel's custom, he was often in the front lines, something he deemed necessary because:

Accurate execution of the plans of the commander and of his staff is of the highest importance. It is a mistake to assume that every unit officer will make all that there is to be made out of his situation; most of them soon succumb to a certain inertia. Then it is simply reported that for some reason or another this or that cannot be done - reasons are always easy enough to think up. People of this kind must be made to feel the authority of the commander and be shaken out of their apathy. The commander must be the prime mover of the battle and the troops must always have to reckon with his appearance in personal control.

The Rommel Papers, p. 226

This is some way beyond 'leading from the front'. Rommel, while being very keen on applying the Auftragstaktik concept to orders from above and 'independently thinking and acting' as stressed in the Truppenfuhrung, also exercised such tight control over his subordinate commanders and units that he practically wiped out any independent thought or deed. From his own experience, Rommel was clearly convinced that such a method of command was vital at a battalion level, and he applied the same principles to divisional command.

When he took command of 7. Panzer-Division in February 1940 Rommel had only limited experience as a field commander. He had commanded only infantry battalions or battalion-sized units previously, and had gained no experience during the 1939 campaign against Poland. In particular, he had never had any experience at all with either motorized or mechanized units. Many other commanders would have considered all these factors as a major hurdle and relied on their staff and subordinate commanders to a great extent. Rommel did not, and, despite the risks involved in this approach, it all worked out well for him. When the German offensive on the Western Front opened on 10 May 1940, Rommel had been in his new command for less than three months, yet within a few weeks his remarkable achievements and the speed with which the division kept moving during its advances would earn it the nickname 'la division fantome' (the ghost division). As a German historian has recently noted, he led his Panzers like an infantry storm troop of World War I - using the same infiltration tactics he had employed as an infantry Leutnant.

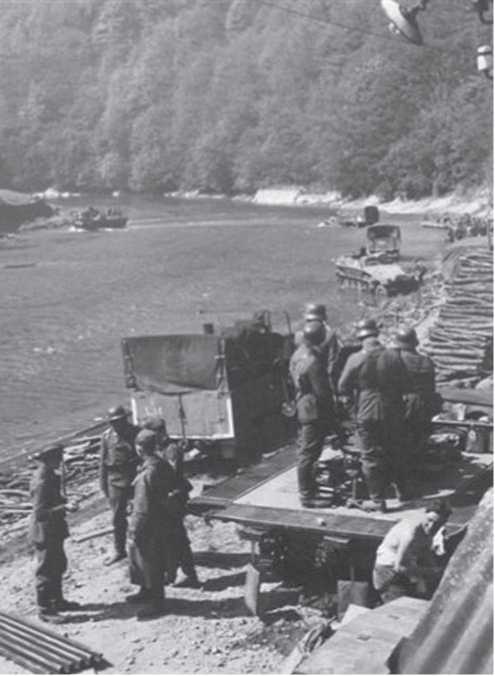

The Meuse at Dinant was the first obstacle in the advance of 7. Panzer-Division. Before a pontoon bridge was built, Rommel used ferries to get his Panzers across the river, which proved to be a decisive step. (HITM)

He had problems from the very beginning with the neighbouring 5. Panzer-Division, whose bulk lagged behind Rommel's division - apart from an advanced armoured detachment that was put under Rommel's command. It was this unit, only temporarily part of 7. Panzer-Division, which established a bridgehead across the Meuse a few kilometres north of Dinant late on 12 May. Rommel eventually split his division into two for the crossing, with one motorized infantry regiment to the north, along with the 5. Panzer-Division, and another motorized infantry regiment with the Panzer regiment to the south, at Dinant. The latter's attempt to get across the river on 13 May saw Rommel performing the role of field commander to perfection; always at the front, he sent Panzer units forwards, coordinated fire support and even arranged for new assault rafts. However, without heavy fire support the attempt failed - once again, according to Rommel, because of the actions of his subordinate officers, who were appalled by the heavy losses and unwilling to press forwards. The following morning, with the divisional artillery now in range, Rommel made another attempt, this time taking personal command of the assault battalion and crossing the Meuse with one of the first assault rafts. Once a bridgehead had been established, Rommel had the divisional engineers building a ferry and then a pontoon bridge, which enabled the first Panzer to get across the river by morning of the 14th.

World History

World History