In the middle of December we marched through Mirzil, Merei, Gura Niscopului, Sapoca, into the Slanicul valley, where we joined the Alpine Corps.

In the plains, the Rumanian resistance stiffened considerably thanks to Russian divisions which had been rushed in as reinforcements. The German Ninth Army slowly fought its way through Buzau to Rimnicul Savat and Fort Focsany. Our gains were at the cost of many casualties. The Alpine Corps received the mission to clear the enemy out of the almost impassable mountain area between the Slanicul and Putna valleys. This would relieve the forces lighting in the plain, and also prevent any hostile advance from the mountains against the forces operating against Focsany.

We spent Christmas Eve deep in the mountains under the most uncomfortable conditions imaginable. Then the 2nd Company marched, in Alpine Corps reserve, from Bisoca through Dumitresti, De Long, Petreanu, to Mera. On January 4, 1917, we rejoined the battalion, whose staff was located in Sindilari. During the same afternoon, the company, reinforced by a heavy machine-gun platoon under the command of Lieutenant Krenzer, occupied Hill 627 about a mile and two thirds northwest of Sindilari. To cover Focsany, strong Rumanian formations held the extensive, rough and heavily wooded mountain of Magura Odobesti (1000 meter elevation).

This mountain was to be taken on January 5. The Bavarian Infantry Life Guards were to be committed from south and southwest and the Wurttemberg Mountain Battalion from southwest and west.

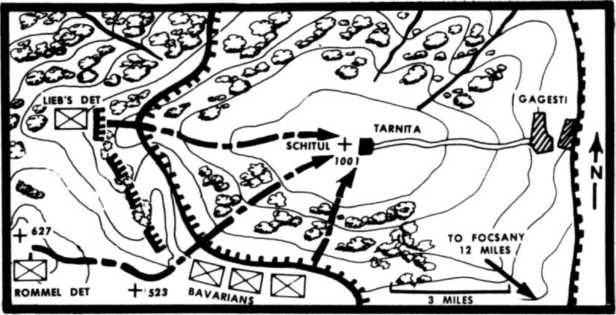

My reinforced company had the mission of seizing Hill 1001 by attacking (without contact on either flank) across Height 523 (a mile and a half northeast of Sindilari). On the right we had the Bavarian Infantry Life Guards with their left wing about four miles to the southeast in the region of Hill 479. Lieb's detachment was on our left on the ridge leading to Hill 1001 from the west. He was some three miles from Hill 627. All these units had the same objective. (Sketch 18)

In accordance with orders, we moved forward at daybreak and, after crossing several deep and wooded valleys, reached Hill 523 at sunrise. An abandoned telescope rendered yeoman service. While the company rested under cover, I studied all the mountain slopes and valleys with the glass and soon became familiar with the disposition and strength of the opposing enemy forces.

Unfortunately, the field of vision did not extend sufficiently to the right to locate the Bavarians on our right. In front of us (in a north-easterly direction) and about a thousand yards away, Rumanian reconnaissance detachments were patrolling the valley. The ridge running in a north-south direction in front of Hill 1001 was completely occupied by Rumanians and sections of entrenched positions were clearly recognizable through gaps between trees. A covered avenue of approach through the broad, treeless valley in front of them was impossible by day. Over on the left, Rumanian combat outposts in about platoon strength stood on the ridge north of Hill 523, which was crowned by single farmsteads and small sections of woods. These outposts were located in entrenched positions facing generally to the west. The most promising avenue of approach to the Magura Odobesti was the ridge running from the west toward the summit along which Lieb's detachment was to be committed. I decided to move closer to Lieb's detachment and to operate in conjunction with him, since an advance in a north-easterly direction without contact to right or left against strong hostile forces seemed hopeless. To be sure, we were still three miles as the crow flies from Lieb, whom I was unable to see and whose presence was only to be presumed. (Sketch 18)

I sent several reconnaissance detachments out with the mission of diverting the enemy's attention from my intended direction of attack (north) and instructed them to rejoin the company within two hours. Shortly after that we succeeded, without losses, in attacking the hostile combat outposts in succession and drove them back to their main position.

We reached a strip of wooded terrain and went to within a mile and a third of the ridge on which we supposed Lieb's detachment to be located. I turned off toward the north with the intention of gaining the ridge running in a north-south direction in front of the Magura Odobesti at the spot where it joined the ridge running from the west toward Hill 1001.

I marched out in front of the column with the company following 150 yards behind. In single file we passed through the sparse woods until we reached a cart road which went down in a ravine. When the scouts had reached the deepest part of the ravine, we noticed movement on the opposite steep slope. A Rumanian column

Sketch 18

Attack against Magura Odobesti (Hill 1001).

With numerous pack animals was descending by zigzagging, with its head only a hundred yards away. Its strength was not discernible. What were we to do?

Apparently the enemy had not noticed us. Quickly I moved the point to one side into the bushes, then withdrew some fifty yards and placed my men in ambush. While this was going on, I sent a runner back to the leading platoon with the order to deploy. Before this was executed, Rumanian rifle fire began to strike among us. The point replied and in a few minutes the 1st Platoon joined the fire fight. Our position in the ravine was unfavourable, for the enemy, whose strength was hard to estimate, was firing from a superior elevation. In a long fire fight, heavy losses on our side were unavoidable. Therefore I decided it was best to attack the unknown forces. The result exceeded expectations. The enemy surrendered when our charge hit him and our bag included seven Rumanians and some pack animals. We suffered no losses.

We rushed up the slope after the retreating enemy and reached

The crest out of breath only to be struck by heavy fire. On the left my brave runner Eppler fell with a shot in the head. After deploying the heavy machine-gun platoon and two infantry platoons, I attacked down both sides of the road in a northerly direction through the high forest. We advanced slowly, unable to see the enemy, the only evidence of his presence being the strong fire humming about our ears. To all appearances the fire became stronger the farther we advanced. Finally we found ourselves lying in a sparse, high forest some three hundred yards from a fortified position. Resistance was so strong that further attack seemed hopeless. A shallow saddle separated us from the hostile position and our position on a forward slope was unfavourable.

To avoid unnecessary losses, I ordered the riflemen to withdraw to the next hill under cover of the heavy machine-gun platoon. This manoeuvre was executed and we found ourselves about a quarter of a mile from the enemy who was occupying a small knoll. The firing died out by degrees and soon only occasional shots were to be heard.

Having no contact on either flank, we formed a hedgehog and began to dig in with the reserve and heavy machine-gun platoons in the centre of our defence area. Darkness was falling as we buried poor Eppler, the only casualty of the skirmish.

Before complete darkness set in we had located elements from Lieb's detachment over on our left on the edge of a glade some eight hundred yards away and had established wire communications with them.

I discussed the situation with First Lieutenant Lieb and later with Major Sproesser. A frontal attack by the two detachments against the strongly fortified Rumanian forest position offered small chance of success. The possibility of an envelopment from the southeast had to be determined without delay.

During the night, Technical Sergeant Schropp made a thorough reconnaissance of the south flank of the hostile position—an extraordinarily difficult task in the rugged terrain. A few hours before daybreak he brought back this excellent bit of information: “We moved off to the northeast, crossed a deep ravine, and managed to reach the ridge behind the enemy position without encountering any hostile forces. Then we crossed a road which is apparently carrying heavy Rumanian traffic.”

I reported these results to Major Sproesser and was ordered to execute the envelopment with two and a half companies. Daybreak was given as the time of attack. Lieb's outfit was to execute a frontal attack only after my unit had launched its attack. At this moment it began to snow heavily.

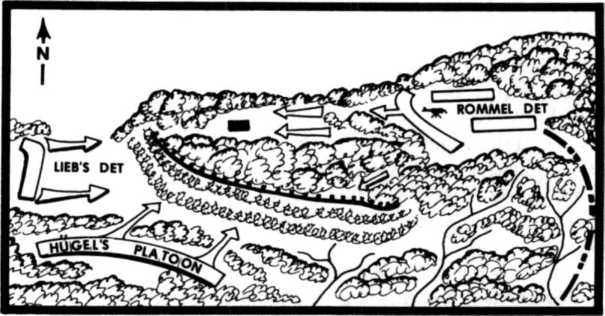

A gloomy day broke on a four-inch blanket of snow. Snow clouds covered the heights. The 6th Company came up as reinforcement. I left Hugel's infantry platoon behind in the old position with the mission of pinning the enemy down by frontal fire and of distracting his attention from us. With one and two-thirds companies and the heavy machine-gun platoon I moved off to the east and climbed down into a very deep ravine. Schropp led since he had been over the route during the night. (Sketch 19)

Hugel opened fire from our old position and had a lively response from the Rumanians who apparently feared an attack. While the fire fight was on, we silently crossed the ravine and climbed in a north-easterly direction. After a hard ascent we gained the ridge and came upon a fresh path in the snow made by Rumanian detachments.

Fog had reduced visibility to less than fifty yards and we expected to run into the enemy at any moment. I ordered the 2nd Company to drop packs and rapidly organized the detachment for attack. The 2nd Company and the heavy machine-gun platoon led with the 6th Company in the second line at my disposal. Except for occasional shots Hugel's fire on the left had died out.

We moved carefully forward astride the ridge road and through the wintry forest toward the enemy west and rear. Suddenly we heard voices before us in the fog. I halted and had the heavy machine gun prepare to open fire. Then we slipped cautiously forward. Suddenly, we reached the edge of an enemy encampment. Although the camp fires were still smoking, no Rumanians were to be seen. We went on until we came upon a clearing in the woods where we saw several unsuspecting Rumanians moving about. How strong was the enemy? We did not know whether we were opposed by a few individuals or by a whole battalion. Preparing for any eventuality, I ordered the heavy machine-gun platoon to open fire on the figures moving in the fog. A few seconds later my whole detachment rushed toward the enemy with loud shouts.

Only a few Rumanians were there and they elected to seek safety in flight rather than to stand and fight. We did not bother with them, but raced along the road to the west. We began to receive fire without being able to locate the enemy, and then after a few minutes we heard the approaching shouts of Lieb's detachment.

We had to be careful to avoid firing on Lieb's men approaching in the fog and forest. We solved this ticklish problem and the enemy between our detachments was eliminated. Most of the Rumanians avoided immediate capture by fleeing downhill and the 2nd Company only gathered in a total of twenty-six prisoners. They only postponed their fate. Three days later when our outfit was

Sketch 19

The envelopment of January 6, 1917. View from the south.

Already on the Putna an entire battalion of five hundred men emerged from the woods and surrendered in a body to the commander of a pack train.

Following our successful attack, which involved no losses on our side, Lieb's detachment headed toward Hill 1001. I ordered the 2nd Company to pick up its discarded packs and then joined the advance. Snow began to drift and the fog became denser.

Near the summit of Hill 1001, Lieb met some Rumanian reserves who had taken up a position in a place sheltered from the wind. The resolute attack of our mountain troops made quick work of them and the Rumanians abandoned the hilltop after suffering some losses. They did not return to their snow-drifted positions.

A cold wind swept over Hill 1001. Ice crystals stung our faces like needles. These weather conditions forced us to hurry our units to the shelter of Schitul Tarnita monastery, which was located a short distance down the east slope of the mountain. The enemy did not block our way. To be sure, the monastery failed to meet our expectations, especially as space and rations were concerned, but at least offered protection against the inclemency’s of the weather. Unfortunately our joy was short-lived.

An hour later some units of the Bavarian Life Guard arrived at Schitul Tarnita and claimed the monastery as their quarters. The Bavarians were our seniors and we had to give in. The Bavarian officer outranked Lieb and myself and we were obliged to move. Lieb managed to keep his people on the monastery proper, but my men had to find shelter in the windy, low-roofed, unheatable earth huts that lay near the monastery. We spent a miserable and bitterly cold night and I decided to push on as soon as possible and find the inhabited region of the valley.

Observations: It was possible to locate and study the hostile positions and dispositions by means of a telescope. This was done during the advance of the company and the results obtained were of equal importance to those prepared by our combat reconnaissance detachments.

In the encounter in the deep and wooded ravine, the vigorous assault of the mountain troops more than compensated for the poor tactical position.

By evening our attack had been stalled some three hundred yards short of the fortified battle area of the Rumanians. To avoid losses, I ordered the rifle platoons on the forward slope of the sparse forest to withdraw to a more favourable position under the fire protection of our heavy guns. No losses ensued. In a similar situation, efficient use could be made of smoke screens. Initially the enemy would maintain a heavy fire into the smoke, but his inability to achieve definite results would oblige him to suspend firing. This would be the moment to begin disengaging operations.

The excellent results of the winter night combat reconnaissance (Technical Sergeant Schropp) made the advance to the rear of the enemy on January 6, 1917 possible. Principle: Reconnaissance must be active while the troops are resting.

To deceive, divert, and pin the enemy down during our envelopment, it was necessary for Hugel to carry out his fire mission for an extended period of time.

During the final phases of the envelopment when we launched an attack in the fog against an enemy of unknown strength, we placed our heavy machine guns well forward and their fire soon cleared the enemy from the ridge.

While the wind was piling the snow in drifts, the Rumanian reserves remained in a protected part of the slope of Hill 1001. This location was such that they were without communication forward and they had neglected to post security elements. Because of this, Lieb’s detachment had little difficulty in surprising and dispersing this strong enemy force.

World History

World History