From the moment the

United States declared war on Germany, a cross-channel invasion of France was at the heart of the plan to defeat Hitler. On the morning of June 6, 1944, that landing— Operation OVERLORD—became a reality.

Invasion Preparation. An enormous effort led up to

The invasion. The United States would furnish sixty divisions for the assault; the British and Canadians another twenty.

President Roosevelt had appointed General Dwight D. Eisenhower Supreme commander of the invasion forces. Roosevelt liked “Ike" and considered him a good soldier and general. More importantly he believed Eisenhower had the political sense to forge cooperation among the other Allied leaders. Eisenhower proved up to the task. When he met with the other invasion commanders he insisted that it mattered less what they agreed to do, than that they all agreed to do it.

Standing His Ground. Eisenhower, though, would not

Pussyfoot around issues he believed essential. His first concern, in preparing for the invasion, was cutting communication lines into France. To do that he would need to use Allied bombers. Most were now busy hitting targets in Germany.

The other Allied air commanders objected to switching the bombing to France, but Eisenhower was adamant. He threatened to resign if the bombers were not made available. The rail lines, as well as bridges, had to be cut to keep the Germans from quickly sending in reinforcements once the Allies had landed.

The bombing raids began in January 1944. After consulting weather and tide reports, the invasion was set for the fifth day of June.

Deceiving the Germans. The Germans were expecting

An invasion across the English Channel, but they didn’t know when or where. The Allies decided to take advantage of German uncertainty. They created a huge fake military buildup and a fictitious army group under General George Patton.

The operation, code-named FORTITUDE, was designed to make the Germans think the invasion would come across the narrowest part of the Channel—at Calais. Workers built fake barracks and depots. The Allies used ULTRA intelligence (see page 116) to make sure the Germans were swallowing the bait.

The real invasion would arrive at Normandy, farther

The pensive, sometimes even stricken face of Dwight Eisenhower became tor many the icon of the United States’ struggle in Worid War ii.

One of seven sons born into a poor Mennonite family,

Eisenhower detoured from his religion’s pacifism to become a West Point cadet.

Some thirty years later he would be Supreme Allied Commander leading the invasion against Hitler’s Fortress Europe.

Within a week of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was called to Washington. In mid-1942 he was sent to London. There he began to oversee plans for what would become the D-Day invasion. Overseeing several Allied generals, some of whose egos rivaled his Texas home state in size, Eisenhower somehow managed to create a working harmony.

While continuing plans for D-Day, Eisenhower led the North African campaign. North Africa was a political and military trial by fire for Ike. When U. S. troops landed at Algiers they were fired on by Vichy French troops, and the French fleet, which might have fallen into German hands, had to be destroyed. Tunisia was near-disaster for green U. S. troops fighting top-of-the-line Germans under Erwin Rommel.

Ike, however, had a capacity to fix what was broken. He learned from the initial horrors of North Africa and from American mistakes in the hard fight in Italy. “(U)nity, coordination and cooperation are the keys,” he wrote while he forged what would become the greatest invasion in the history of the world.

Though Eisenhower planned D-Day with some confidence, others were wary of a potential disaster. Eisenhower’s air commander, for example, had predicted that U. S. airborne divisions (who would be dropped during the night before the invasion) would suffer 70 percent casualty rates. Eisenhower believed the airborne troops were essential to protect the invasion. Still, he was conscious of the terrible risk these soldiers were taking. The night before the invasion, as the airborne troops were getting ready to fly over the channel, Eisenhower stood among them. He walked through their lines, asked their names, and where they were from. He clamped them on the shoulders and wished them luck. As each plane departed in the dark, the four-star-general stood on the runway, his hand raised in salute.

Eisetiltower wishes luck to paratroopers ready to emplane for Normandy, where they would be dropped behind enemy lines.

South on the French coast. Amphibious (land and sea) forces from three nations would storm five beaches, code-named UTAH (American), OMAHA (American), JUNO (Canadian), SWORD (British), and GOLD (British). Three airborne divisions would be dropped in to protect the flanks of the invasion force.

Naval gunfire would “soften up” the German defenses before the landing started. Allied planes, now in control of the air around the coastline, would protect the beaches from a German counterattack by air.

Germans Prepare. General Erwin Rommel, who had given the Allies so much trouble in North Africa, was now in charge of defending the French coast. He had two armies under his control. One was positioned at the Pas de Calais, where the Germans expected the invasion. The other was stationed farther southwest, in Normandy and Brittany.

The Germans knew that the invasion was on the horizon, and they expected it would come soon, but they thought it would come at Calais. Bad weather over the channel just before the invasion helped to keep them in the dark. They were quite sure the Allies would not risk a landing during the coming storm.

Rommel was so certain nothing was happening, he went home to Germany for his wife’s birthday. It was probably the mistake of his life.

Storm Front. Heavy squalls over the channel had threatened to cancel the June invasion altogether. Severe winds and rain would make the invasion crossing nearly impossible. Tanks and divisions could not land on the beach in five-foot waves.

Eisenhower was beside himself with worry. If he delayed, all the carefully made plans for the inv'asion might collapse. If he okayed it, the storm might turn the landing into a suicide. In the end he delayed for a day, okaying the invasion to begin June 6, with a break in the weather.

All in Reaoiness. On June 5, the preparations for

D-Day, the Normandy landing, were completed. The great invasion would be on a scale larger than any before it. Aircraft, ships, men, and supplies—in quantities never seen before or since—prepared to depart fi'om the south of England.

A line of trucks leaving from Dov'er formed such a gridlock that an ice-cream truck, stuck in the middle of the convoy, got sent to France th the im'ading forces.

Among many of the commanders on the eve of the invasion, there was a feeling of deep dread. Many of the British officers had experienced the humiliating evacuation of Dunkirk. They could not help but fear a repeat disaster.

Eisenhower himself was v'exed with worry. In his pocket was a speech he had written should the invasion collapse. "Our landings...have failed.... The troops, the Air and Navy did all that hraveiT and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.”

D-Day

During the night of June 5-6,

1944, thousands of ships filled with invasion troops left from ports in England. Most of the Americans were unblooded soldiers—they had never seen battle before. Now they would be facing crack German divisions behind iron defenses.

The Landing. The seas, churned and swelled by the squalls, made many seasick along the way. A few talked. Most smoked cigarettes, nursed their sick stomachs, or slept. Some spent time praying. Almost all wondered if they would still be alive in a few hours.

As the thousands of ships approached the beaches, the U. S. fleet’s big guns began to slam the Normandy cliffs with shell fire. The more damage done to the Germans from a distance, the easier it would be for the men wading ashore.

But it would be no seaside picnic. Rommel had spent months stiffening the coastal defenses, burying millions of mines all along the coast. Obstacles laced the shallow water to keep boats, or anything else, from landing.

Airborne Units. At dawn Allied troops struggled onto the landing beaches; some British and American soldiers were already roaming deeper inside Normandy. Three divisions, a total of 23,400 paratroopers—including the 82nd and 101st American airborne units—had been dropped into the Normandy fields during the night.

Like the soldiers on the beaches, their welcome onto French soil was hardly hospitable. Dropped off-target in a fog, some actually fell into the ocean. Others, still inside the plane, were hit with antiaircraft fire before they got a chance to jump. Some were dropped too low for their parachutes to open and smashed "like ripe pumpkins." Others fell into the flooded ditches of the Normandy fields and tangled in their parachutes.

Allied troops also came in by glider. These "flying coffins” sometimes proved the worst method of any for getting into France on D-Day. Whole crews were killed when the planes crashed into hedgerows or "Rommel's asparagus” (poles planted in open spaces by the Germans to keep the gliders from landing).

The airborne units were supposed to be dropped much closer together than they actually were, and many were lost on the ground. In a nightmarish scenario, GIs had to find each other without alerting the Germans lurking all around them. To signal friendlies, troops used a small clicker that made a noise like a cricket. Through the night they gathered into groups and went about their missions, taking strategic bridges and crossroads and crushing German positions. They took staggering casualties, but their efforts protected the landing beaches from a German counterattack.

Death at Omaha. Allied soldiers met resistance at all the invasion beaches, but the worst fight came at Omaha. The Americans who landed there had the misfortune to arrive during a German training exercise.

The seas were still high fl-om the storm, and many

Arie-Louise Osmont was a widow living on her farm in Normandy when World War II broke out. Osmont’s home was occupied first by the

Germans and later by the British. She fought to keep her life and home in some state ot order during the occupations. She also managed to keep a detailed diary, which was published in 1995.

Osmont’s descriptions of the events just after the invasion are especially fascinating. On June 7, she was wounded as a dogfight went on above her. The passage below makes clear the chaos and terror of those hours: ‘Very early in the morning, German airplane [is] shot down in the field of rapeseed. The aviators (young men) tried to jump with parachutes, but in vain. The bodies are badly damaged, burned, hands still clenched on their parachutes.

“Around six o’clock in the morning, dead quiet. We emerge into the coolness of this new day and I go delightedly to stretch out on my bed for a bit. Tm driven from it about eight 0 'clock by intense cannon fire. Above our heads, sudden and horrifying, an airplane battle. I hug the walls of the outbuildings: I’m terrified. I want to get to the trench, to escape these machine-gun bullets that smack everywhere. I run; when I get to the turn that leads to the farmyard I throw myself flat on the ground, bewildered, glued to the slope. Suddenly everything’s erupting, everything's falling around me, I feel a painful blow to the small of my back. I see balls of fire a few meters in front of me. I raise my head instinctively and catch sight of an airplane falling in flames. ”

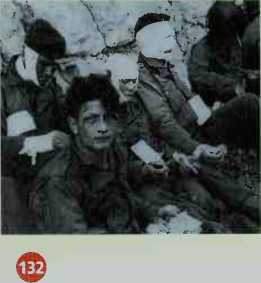

Seasick and scared, American troops wade toward Omaha Beach. Casualties in the first vvflves passed ninety percent.

Landing craft foundered, drowning the men inside them. Tanks, specially designed to "swim” onto the beaches, toppled in the surf and sank to the bottom. Burning oil floated on waves, as soldiers desperately tried to wade ashore in a storm of fire.

“Almighty God, our sons, pride of our nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor... to set free a suffering humanity. ”

—President Roosevelt’s prayer on D-Day

Of the first wave of troops at Omaha, 75 percent were cut down before they made it off the beach. Sheer terror sent a few panic-stricken and screaming back to the boats.

There was no place to run, though—German fire fell all around them. Wave after wave of desperate men somehow struggled toward the beaches. Eventually U. S. Army Rangers and other intrepid soldier. s clawed their way up the cliffs to silence the German defenders.

By midmoming, the beach was strewn with dead and dying men. Water-fouled guns, wrecked tanks, blankets, and blood were everywhere. Five thousand men had died, but the worst was over. By midnight the area around Omaha and the other beaches was secured.

Hitler, having issued strict orders that no one wake him, slept through the great invasion.

To THE East. The fiihrer had promised that the Allies would get “the thrashing of their lives" if they tried to invade France. His pi'ediction, at least for the Americans, proved correct. They did get the thrashing of their lives at Omaha Beach.

But it did not stop them. Hitler had banked upon destroying the invasion force on the beaches. But his strategy failed. The Allies used their control of the air to secure those blood-bought acres of ground. In a few days the troops were off the sand and into the pastures of Normandy.

In less than two months, 1.5 million men would land in France. In a very short time the Americans would recover from their losses on the beaches. They would be ready to thrash back, aiming their armor east, toward Hitler and Germany’s heart.

World History

World History