Gabreski, Col Francis S (b. l919). US. As a member of the US 56th Fighter Group. Gabreski became the top-scoring American fighter pilot in the European Theatre of Operations during World War II, with 28 confirmed victories between August 1943 and July 1944. Later, in Korea, he added 6.5 MiG-15s to his total.

Galician campaign (1914). As the Russians moved into East Prussia, a huge battle was developing farther south, where the Austro-Hungarians faced four Russian armies across the Galician border. In August 1914, the Habsburg empire had mobilized 3,350,000 men of all categories of whom some

1,400,000 could be regarded as front-line combat troops. This huge army consisted of many distinct racial groups: Austro/

German, 28 percent: Slavs, 44 percent; Hungarian/Magyar, 18 percent; Italian 8 percent; Romanian, 2 percent. Slavs made up 67 percent of the infantry and their loyalties were inclined to the Russians rather than their German allies. In a war in which infantry were to play a key role, the Austro-Hungarians could field 1,100 battalions, of which 700 were fit for front-line duty. The German and Hungarian-speaking regiments would prove the steadiest, whilst Czechoslovak units surrendered in droves rather than fight their fellow Slavs.

In charge of this heterogeneous army was Field Marshal Baron Conrad von Hdtzendorff, its Chief of General Staff. Universally respected, he was an able strategist commanding a tactically defective instrument. His army was short of

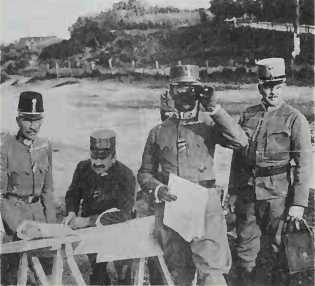

Austro-Hungarian officers, Galicia. 1914

Modern artillery and standardized small arms, thus adding to logistic problems. The officer corps was competent and conscientious, and with racial differences in mind, close attention was paid to man-management. The common language was a patois known as “Army Slav”, in addition to which all recruits, in theory, understood up to 80 German words of instruction and command.

Conrad’s staff had estimated that by August 20 there would be 31 Russian divisions on the Galician front, rising to 52 by August 28 when the Russians would have a 4:3 superiority. A pre-emptive Austrian offensive was therefore considered essential. On August 20, Conrad attacked. His two best armies, the First (Dankl) and Fourth (Auffenberg), were on the left, advancing northeast into Poland with Dankl’s left flank on the River Vistula, whilst the Third, from its position in front of the fortress of Lemberg, covered the right flank of the Fourth. On the Russian side, Ivanov’s South West Army Group (Fourth, Fifth, Third and Eighth Armies) was deploying behind the Russian frontier. The Fourth Army, still not fully mobilized, immediately advanced towards the Austrian First Army and was repulsed at Krasnik on August 23. Ivanov ordered Plehve’s Fifth Army to wheel right and take Dankl in the flank, but no sooner had this move been initiated than its own left flank was caught in turn by Auffenberg’s Fourth Army. A huge melee ensued, with Conrad drawing troops away from Lemberg to reinforce Fourth Army, giving the Russians local numerical superiority on which they managed to capitalize. On August 27 the Austrians began to break, but the Russian follow-up was slow. However, Brusilov’s Eighth Army now attacked decisively in the south and the Austrians fled.

Conrad evacuated Lemberg on September 2 but persisted with Fourth Army’s advance on the left, despite the total collapse of his right, and failed to destroy the Russian Fifth Army which had rashly advanced too far. Great gaps, rapidly filling with Russians, were now opening up between the Austrian armies, but Conrad was still issuing brilliantly-conceived

Plans which could not be implemented. On September 11, the Austrians intercepted an unciphered Russian signal revealing Ivanov’s intentions. This prompted Conrad to order a withdrawal behind the line of the River San.

The Russians, with chaotic lines of communication and exhausted by continual forced marches, failed to pursue. Conrad threw a huge garrison into the fortress of Przemysl and continued his withdrawal to the line of the Dunajec. Galicia had fallen to the Russians and the Austrians had lost 350,000 out of 900,000 men committed to battle. There were bitter recriminations against the Germans who, it was felt, should have hastened south from East Prussia to the rescue. But Hindenburg had other affairs in train. MH. See also

WARSAW, BATTLE OF (l914).

Galland, Gen Adolf (b. l912). Ger. An outstanding fighter pilot of World War II, having gained combat experience in the Spanish Civil War. He was among the topscoring German pilots in the Battle of Britain and “Circus” operations, 1940—41; eventually credited with 103 victories. Galland became General of the Fighter Arm in late 1941, with responsibility for the night fighter force also following Kammhuber’s departure in 1943. His position did not give him executive command: he had direct access to Goring and, not infrequently, to Hitler, but his situation was fundamentally unsound, for Goring’s intrusive impulsiveness and Hitler’s failure to understand the fundamentals of air power made the development of systematic policies impossible.

Gallieni, Marshal Joseph (18491916). Fr. Gallieni fought as an infantry officer in the Franco-Prussian War and spent 30 years in colonial service, becoming Governor of Madagascar from 1896 to 1905. In 1911, nearing retirement, he declined the post of Chief of the General Staff, recommending Jof-fre, a former subordinate in Madagascar, as a candidate. Gallieni was recalled to duty at the start of World War I and nominated as Joffre’s successor in case of emergency, but the latter felt he was a potential threat and kept him away from the French General Headquarters. On August 26 1914 Gallieni was appointed Military Governor of Paris. Eight days later, on September 3, he recognized the chance offered by Kluck’s wheel west of Paris, directing Maunoury’s Sixth Army to prepare to attack the exposed German flank. On September 4 Joffre, who had considered withdrawing farther south, backed Gallieni’s proposal. This led to the Allied victory on the Marne, though Gallieni’s critics claim that Maunoury’s attack was launched prematurely, enabling the Germans to avoid total disaster. Gallieni remained Military Governor of Paris until October 1915, when Briand made him Minister of War. Dissatisfied with the conduct of operations, Gallieni tried to move Joffre aside and give de Castelnau command of the field armies. However, Briand was reluctant to risk the probable political furore which would have resulted and Gallieni himself resigned in March 1916. Already ill, he died in May. He was posthumously created Marshal in 1921. PJS.

Gallipoli (1915-16). After the failure of the Anglo-French naval operation to force the Dardanelles, all now rested on a land campaign. In late February 1915 the Turks were in disarray and Allied landing parties went ashore unopposed to demolish batteries left intact by the earlier naval bombardment; but with the appearance in Constantinople of the formidable Gen Liman von Sanders as head of the German military mission, and the timely arrival of Lt Col Mustafa Kemal “Ataturk” as commander of the Turkish Army’s Gallipoli garrison, the defence was galvanized into activity.

On March 13 1915, Gen Sir Ian Hamilton, appointed by Lord Kitchener to direct the Gallipoli landings, left London. Four days later he joined the fleet off the Dardanelles, where confusion reigned. The ships carrying the British 29th Division, assigned to lead the operation, had been loaded piecemeal and dispatched to the Eastern Mediterranean without proper plans for disembarkation, and Hamilton had to shift his base to Alexandria, where major logistic reorganization was necessary. The naval commander.

Heavy howitzer in action at Gallipoli

Vice Adm de Robeck, told Hamilton on March 22 that his ships could no longer enter the Narrows because of strengthened coastal batteries and new minefields. Nevertheless, Hamilton devised a sound plan for the landings: to seize the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula prior to a victorious advance on Constantinople. That the defenders were given sufficient time to prepare themselves was not entirely Hamilton’s fault. The Allied landings took place on April 25 - a full month after Liman von Sanders’ appointment as commander of the Turkish Fifth Army, during which time great progress had been made on the beach defences. Hamilton’s plan was for a series of landings under the guns of the fleet. These had been carefully planned, with feints to north and south and diversionary landings by French marines on the southern side of the Straits. However, the Turks were waiting for the 29th Division at Helles and despite the gallantry of the British infantry a narrow lodgement was only secured at terrible cost. The landing of the Australian and New Zealand Corps (anzacs) at Gaba Tepe was initially unopposed, but Mustafa Kemal’s quick reaction to this crisis soon pinned them down.

The expedition was now effectively stranded. The formations ashore were hemmed in, and the Turks fiercely repelled any attempt at a breakout. In an effort to get the campaign going again, Hamilton put two further divisions ashore to the north, at Suvla, on August 6, achieving complete tactical surprise. However, the general in command ashore, Stopford, made no attempt to exploit inland. The Turks quickly contained this second landing and stalemate set

In again. As summer gave way to an unseasonably cold autumn, conditions for both sides became appalling, with disea. se claiming as many victims as the fighting, in which the anzac troops distinguished themselves. In November, no decision having been obtained. Kitchener visited the peninsula to see things for himself and signalled Whitehall that the anzac and Suvla beachheads must be evacuated forthwith. Hamilton was superseded as c-in-c by Gen Sir Charles Monro and the energetic Lt Gen Sir William Birdwood (anzac commander) took command of all troops ashore. Between them, they prepared a brilliant evacuation plan, executed without the loss of a man on the night of December 19—20. A similar operation took place at Helles on the night of January 8-9 1916.

There were many reasons for the failure of this initially promising campaign. The amphibious landings should have been carried out at the time of the earlier naval operation; as it was, the enemy had four weeks in which to prepare for the obvious. Gross breaches of security by the Allies gave the highly-developed German Intelligence Service ample warning. Hamilton’s scratch force of largely under-trained troops was actually outnumbered at the start of the campaign, and subordinate commanders like Stopford and Hunter-Weston (commanding 29th Division) made matters worse by failing to capitalize on the success of many of the initial landings. The sensitive and compassionate Hamilton was reluctant to drive his men or sack their commanders when this would have gained a decision. His plan was imaginative and radical, but the wherewithal for its execution was absent. The Turkish soldier, stoic and courageous, proved a formidable opponent. Amphibious landings demand high standards of training and much rehearsal if they are to succeed, and no amount of heroism could have saved this operation once it was launched. Out of

410,000 British and Empire troops and 70,000 French committed to battle, 252,000 were killed, wounded, missing, prisoners or victims of disease. Turkish casualties were 218,000, of whom 66,000 were killed in action. MH.

World History

World History