BRITAIN ENTERED THE TWENTIETH CENTURY IN THE GRIP OF WAR. She placed nearly half a million men in the field, the biggest force she had hitherto sent overseas throughout her history. The conflict in South Africa, which began as a small colonial campaign, soon called for a large-scale national effort. Its course was followed in Britain with intense interest and lively emotion. Scarcely a generation had gone by since the Franchise Acts had granted a say in the affairs of State to every adult male. The power to follow events and to pass judgment upon them had recently come within the reach of all through free education. Popular journals had started to circulate among the masses, swiftly bringing news, good, bad, and sometimes misleading, into millions of homes. Yet the result of this rapid diffusion of knowledge and responsibility was not, as some had prophesied, social unrest and revolutionary agitation. On the contrary, the years of the Boer War saw a surge of patriotism among the vast majority of the British people, and a widespread enthusiasm for the cause of Empire.

Of course there were vehement critics and dissentients, the pro-Boers, as they were derisively called. They included some influential Liberal leaders, and in their train a rising young Welsh lawyer named Lloyd George, who now first made himself known to the nation by the vigour of his attacks upon the war and the Government. Nevertheless the general feeling in the country was staunchly Imperialist. There was pride in the broad crimson stretches on the map of the globe which marked the span of the British Empire, and confidence in the Royal Navy’s command of the Seven Seas. Europe was envious. Most of the Powers made plain their sympathy for the Boers, and there were hints of an allied combination against the Island kingdom. She might not have been allowed to escape from her colonial war with an easy victory, but her dominion of the seas caused second thoughts. On the outbreak of war a flying squadron of the Royal Navy was mobilised at Portsmouth, and this upon consideration from many angles proved effective in overawing Europe. The lesson was not lost upon the German Kaiser.

The spectacle of British sea-power exercising unchallengeable authority made him redouble his efforts to create a mighty ocean-going German battle fleet. Dire consequences were to flow from his spirit of emulation.

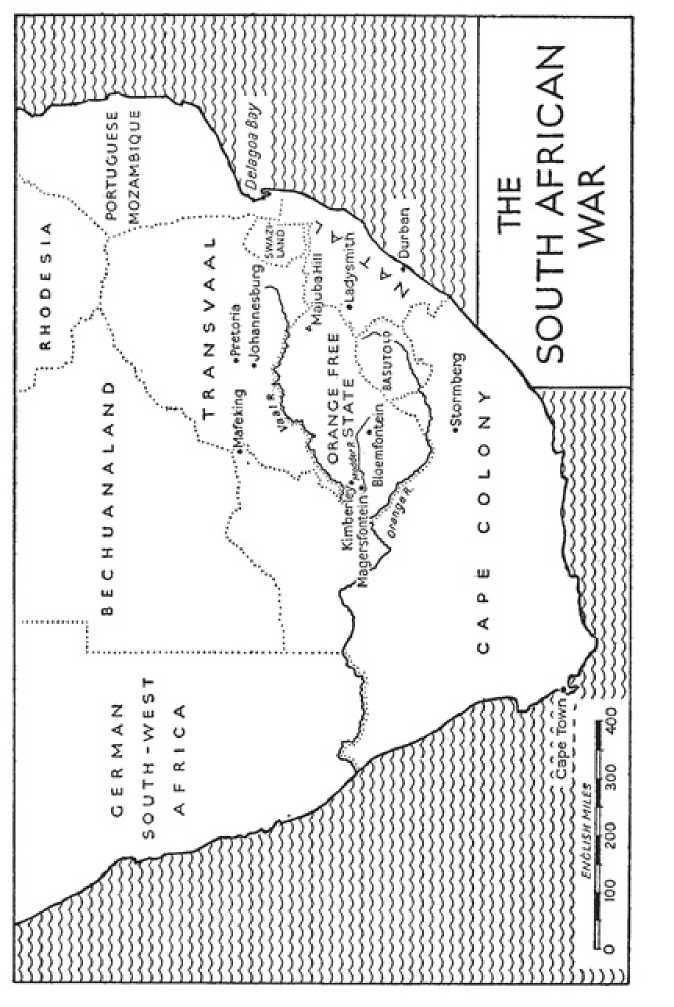

The South African War had its roots deep in the past. Two land-locked Boer Republics, owing a vague suzerainty to Britain, were surrounded on all sides, except for a short frontier with Portuguese Mozambique, by British colonies, protectorates, and territories. Yet conflict was not at first inevitable. The large Dutch population in Cape Colony appeared reconciled to British rule and supported Cecil Rhodes as their Premier. The Orange Free State was friendly, and even in the Transvaal, home of the dourest frontier farmers, a considerable Boer party favoured cooperation with Britain. Hopes of an Anglo-Boer federation in South Africa were by no means dead. But all this abruptly changed during the last five years of the nineteenth century.

When Joseph Chamberlain became Colonial Secretary in 1895 he was confronted by a situation of great complexity. The Transvaal had been transformed by the exploitation of the extremely rich goldfields on the Witwatersrand. This was the work of foreign capital and labour, most of it British. Within a few years Johannesburg had developed into a great city. The Uitlanders—or Outlanders, as foreigners were called—equalled the native Boers in number, but the Transvaal Government refused to grant them political rights, even though they contributed all but one-twentieth of the country’s taxation. Paul Kruger, the President of the Republic, who had taken part in the Great Trek and was now past his seventieth year, determined to preserve the character and independence of his country. He headed the recalcitrant Dutch, unwilling to make common cause with the British, and opposed to the advance of industry, though ready to feed on its profits. The threat of a cosmopolitan goldfield to a close community of Bible-reading farmers was obvious to him. But his fears were intensified by the encircling motions of Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, which already controlled the territories to the north that were to become the Rhodesias, and was now trying to acquire Bechuanaland to the west. Rhodes, who had large financial interests on the Rand, dreamt of a

United South Africa and a Cape-to-Cairo railway running through British territory all the way.

The political and economic grievances of the Uitlanders made an explosion inevitable, and Chamberlain by the end of 1895 was ready to meet it. Unknown to him however Rhodes had worked out a scheme for an uprising of the British in Johannesburg to be reinforced by the invasion of the Transvaal by a Company force. This was to be led by the Administrator of Rhodesia, Dr Leander Starr Jameson. At the last moment the rising in Johannesburg failed to take place, but Jameson, not having counter-instructions from Rhodes, invaded the Transvaal with five hundred men on December 29. It was, in Chamberlain’s words, “a disgraceful exhibition of filibustering,” and it ended in the failure which it deserved. On January 2 Jameson and his force surrendered to the Boers at Doornkop. The raid was a turning-point; the entire course of South African history was henceforth violently diverted from peaceful channels. The atmosphere of the country was poisoned by national and racial prejudice; the Dutch at the Cape, in natural sympathy with the Transvaal Boers, began to growl at the British. Rhodes was forced to resign his Premiership; but his great popularity in England served only to sharpen Boer suspicion of a deep-laid plot against the life of their republics. The Orange Free State threw in its lot with Kruger. In the Transvaal his purpose was strengthened; the party of reaction gained the upper hand and armaments were purchased on a large scale for the conflict that loomed ahead.

The next three years were occupied by long-drawn-out and arduous negotiations, Chamberlain’s determination being more than matched by Kruger’s tortuous obstinacy. In March 1897 Sir Alfred Milner, an outstanding public servant, became High Commissioner in South Africa. He was an administrator of great talents, but he lacked the gift of diplomacy. Within a few months he had made up his mind; he wrote to Chamberlain, “There is no ultimate way out of the political troubles of South Africa except reform in the Transvaal or war. And at present the chances of reform in the Transvaal are worse than ever.” But Chamberlain was anxious to avoid war, except as a last resort, and even then he hoped that the responsibility for its outbreak could be fixed on the Boers. He believed, as did Rhodes, that Kruger, under pressure, would yield. They underestimated the pioneers of the veldt.

The climax was reached in April 1899, when a petition, signed by more than 20,000 Uitlanders, arrived in Downing Street. It was followed in May by a dispatch from Milner which stated that “The spectacle of thousands of British subjects kept permanently in the position of helots. . . does steadily undermine the influence and reputation of Great Britain and the respect for the British Government within the Queen’s Dominions.” A period of negotiation followed, with the British Government demanding a vote for every citizen after five years’ residence in the Transvaal and putting forward the old claim to “suzerainty.” A conference at Bloemfontein in June between Kruger and Milner settled nothing. Milner was convinced that the Boers, now armed to the teeth, were aiming at the establishment of a Dutch United States of South Africa. Kruger was equally convinced that the British intended to rob the Boers of their freedom and independence. “It is our country you want,” he said, as tears ran down his face. Chamberlain made several more attempts to come to an agreement, but by this time both sides were pressing ahead with military preparations. On October 9 the Boers delivered an ultimatum while the British forces in South Africa were still weak. Three days later their troops moved over the border.

At the outbreak of the war the Boers put 35,000 men, or twice the British number, in the field, and a much superior artillery derived from German sources. They crossed the frontiers in several directions. Their army was almost entirely mounted. They were armed with Mannlicher and Mauser rifles, with which they were expert shots. Within a few weeks they had invested Ladysmith to the east, and Mafeking and Kimberley to the west. At Ladysmith, on the Natal border, 10,000 men, under Sir George White, were surrounded and besieged after two British battalions had been trapped and forced to surrender with their guns at Nicholson’s Nek. At Mafeking a small force commanded by Colonel Baden-Powell was encircled by many times its number under Pete Cronje. At Kimberley Cecil Rhodes himself and a large civilian population were beset. After the seasonal rains there was fresh grazing on the veldt, which had been deliberately stimulated by Boer burnings at the end of the summer. The countryside was friendly to the Boer cause. World opinion was uniformly hostile to the British. Meanwhile a British army corps of three divisions was on the way as reinforcement, under the command of Sir Redvers Buller, and volunteer contingents from the Dominions were offered or forthcoming. The phrase “unmounted men preferred” used in official correspondence was typical of the want of knowledge prevailing at the War Office. The troops were good, but the enemy weapons and conditions were entirely misunderstood.

Kruger had long wanted a salt-water port under his independent control. Beyond the mountain passes of Natal lay Durban harbour, which could be captured if only he could reach it. Durban was linked with the Transvaal by a railway which, by comparison with the long line to Cape T own, was short, manageable, and on his doorstep. Here would be the end of many disputes about customs dues, freight charges, and much else besides, and it was in this region that the main effort of both sides was at first concentrated.

The British army corps, as it arrived, was distributed by Buller in order to show a front everywhere. One division was sent to defend Natal, another to the relief of Kimberley, and a third to the northeastern district of Cape Colony. Within a single December week each of them advanced against the rifle and artillery fire of the Boers, and was decisively defeated with, for those days, severe losses in men and guns. At Colenso, in Natal, where Buller himself commanded, at the Modder River on the road to Kimberley, and at Stormberg in the east of Cape Colony the Boers held their front and invaded the country before them. Although the losses of under a thousand men in each case may seem small nowadays, they came as a startling and heavy shock to the public in Britain and throughout the Empire, and indeed to the troops on the spot. But Queen Victoria braced the nation in words which have become justly famous. “Please understand,” she replied to Balfour when he tried to discuss “Black Week,” as it was called, “that there is no one depressed in this house. We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. They do not exist.” Lord Roberts of Kandahar, who had won fame in the Afghan Wars, was made the new Commander-in-Chief, Lord Kitchener of Khartoum was appointed his Chief of Staff, and in a few months the two already illustrious generals with an ever-increasing army transformed the scene. Buller meanwhile persevered in Natal.

The new British command saw clearly that forces must be used on a large scale and in combination, and the Boer capitals, Bloemfontein and

Then Pretoria, became their sure objective. Cronje at Mafeking was deceived into thinking that the main blow would fall on Kimberley, and he shifted the larger portion of his troops to Magersfontein, a few miles south of the diamond centre. Here he entrenched himself and awaited the attack. Kimberley indeed was one of Roberts’ objectives, but he gained it by sending General French on a long encirclement, and French’s cavalry relieved it on February 15. The threat from the rear now compelled Cronje to quit his earthworks and fall back to the northeast. Twelve days later, after fierce frontal assaults by Kitchener, he surrendered with four thousand men. Thereafter all went with a rush. On the following day Buller relieved Ladysmith; on March 13 Roberts reached Bloemfontein, on May 31 Johannesburg, and on June 5 Pretoria fell. Mafeking was liberated after a siege which had lasted for two hundred and seventeen days, and its relief provoked unseemly celebrations in London. Kruger fled. The Orange Free State and the Transvaal were annexed, and in the autumn of 1900 Roberts went home to England. After almost exactly a year of lively fighting, and with both the rebel capitals occupied, it seemed to the British people that the Boer War was finished, and won. At this Lord Salisbury, on Chamberlain’s advice, fought a General Election and gained another spell of power with a large majority.

On January 22, 1901, Queen Victoria died. She lay at Osborne, the country home in the Isle of Wight which she and Prince Albert had designed and furnished fifty-five years before. Nothing in its household arrangements had been changed during the Queen’s long widowhood. She had determined to conduct her life according to the pattern set by the Prince; nor did she waver from her resolution. Nevertheless a great change had gradually overtaken the monarchy. The Sovereign had become the symbol of Empire. At the Queen’s Jubilees in 1887 and 1897 India and the colonies had been vividly represented in the State celebrations. The Crown was providing the link between the growing family of nations and races which the former Prime Minister, Lord Rosebery, had with foresight christened the Commonwealth. Disraeli’s vision and Chamberlain’s enthusiasm had both contributed to this broadening Imperial theme. The Queen herself was seized with the greatness of her role. She sent her sons and grandsons on official tours of her ever-increasing dominions, where they were heartHy welcomed. Homage from a stream of colonial dignitaries was received by her in England. She appointed Indian servants to her household, and from them learnt Hindustani. Thus she sought by every means within her power to bind her diverse peoples together in loyalty to the British Crown, and her endeavours chimed with the Imperial spirit of the age. One of her last public acts, when she was over eighty years of age, was to visit Ireland. She had never believed in Irish Home Rule, which seemed to her a danger to the unity of the Empire. Prompted by a desire to recognise the gallantry of her Irish soldiers in South Africa, she travelled to Dublin in April 1900, wearing the shamrock on her bonnet and jacket. Her Irish subjects, even the Nationalists among them, gave her a rousing reception. In Ireland a fund of goodwill still flowed for the Throne, on which English Governments sadly failed to draw.

In England during the Queen’s years of withdrawal from the outward shows of public life there had once been restiveness against the Crown, and professed republicans had raised their voices. By the end of the century all this had died away. High devotion to her royal task, domestic virtues, evident sincerity of nature, a piercing and sometimes disconcerting truthfulness-all these qualities of the Queen’s had long impressed themselves upon the minds of her subjects. In the mass they could have no knowledge of how shrewd she was in political matters, nor of the wisdom she had accumulated in the course of her dealings with many Ministers and innumerable crises. But they justly caught a sense of a great presiding personage. Even Ministers who in private often found her views impulsive and partisan came to respect the watchful sense of duty that always moved her. She represented staunchness and continuity in British traditions, and as she grew in years veneration clustered round her. When she died she had reigned for nearly sixty-four years. Few of her subjects could remember a time when she had not been their Sovereign. But all reflecting men and women could appreciate the advance of British power and the progress of the British peoples that had taken place during the age to which she gave her name. The Victorian Age closed in 1901, but the sense of purpose and confidence which had inspired it lived on through the ordeals to come.

The war in South Africa meanwhile continued. In the past the Boers had never shown themselves docile or obedient to political authority, even when exercised by their own leaders, and British occupation of their principal townships and British seizure of the railways seemed an insufficient reason for abandoning the struggle. The veldt was wide, and from its scattered farmhouses a man could get news, food, shelter, forage, a fresh horse, and even ammunition. Roberts and Buller had hardly left the shores of South Africa when the war flamed into swift-moving, hard-hitting guerrilla. Botha, Kritzinger, Hertzog, De Wet, De la Rey, to name only five of the more famous commando leaders, soon faced Kitchener with innumerable local battles and reverses which were not to end for another seventeen months. The Boers were only to be subdued by extraordinary British exertions. In February 1901 Botha struck at Natal, and was thrown back by General French after laying waste large areas of the country. The other leaders invaded Cape Colony, hoping to rally its Dutch inhabitants. Very few responded, but they were enough to destroy all hopes of a speedy peace. After the raiders were expelled Kitchener and Botha met at the end of the month to arrange terms. Each of these leaders wanted an amnesty for the Cape rebels; but Milner, the High Commissioner, was adverse, and the Cabinet in London supported him. Thus frustrated, and much against his judgment and personal inclination, Kitchener was driven to what would nowadays be called a “scorched earth” policy. Blockhouses were built along the railway lines; fences were driven across the countryside; then more blockhouses were built along the fences. Movement within the enclosures thus created became impossible for even the most heroic commandos. Then, area by area, every man, woman, and child was swept into concentration camps. Such methods could only be justified by the fact that most of the commandos fought in plain clothes, and could only be subdued by wholesale imprisonment, together with the families who gave them succour. Nothing, not even the incapacity of the military authorities when charged with the novel and distasteful task of herding large bodies of civilians into captivity, could justify the conditions in the camps themselves. By February 1902 more than twenty thousand of the prisoners, or nearly one in every six, had died, mostly of disease. At first the authorities denied that anything was wrong, or that any alleviation was possible, but at length an Englishwoman, Miss EmUy Hobhouse, exposed and proclaimed the terrible facts. Campbell-Bannerman, soon to be Prime Minister, but at this time in Opposition, denounced the camps as “methods of barbarism.” Chamberlain removed them from military control; conditions thereupon speedily improved, and at last, on March 23, 1902, the Boers sued for peace.

Three days later Cecil Rhodes died of heart disease. In one of his final speeches he thus addressed the Loyalists of Cape Town: “You think you have beaten the Dutch. It is not so. The Dutch are not beaten. What is beaten is Krugerism, a corrupt and evil Government, no more Dutch in essence than English. No! The Dutch are as vigorous and unconquered today as they have ever been; the country is still as much theirs as yours, and you will have to live and work with them hereafter as in the past.” Certainly the peace which was signed at Vereeniging on May 31 tried to embody this spirit, and its provisions may be judged magnanimous in the extreme. Thirty-two commandos remained unbeaten in the field. Two delegates from each met the British envoys, and after much discussion they agreed to lay down their arms and ammunition. None should be punished except for certain specified breaches of the usages of war; self-government would be accorded as soon as possible, and Britain would pay three million pounds in compensation. Such, in brief, were the principal terms, of which the last may be reckoned as generous, and was at any rate unprecedented in the history of modern war. Upon the conclusion of peace Lord Salisbury resigned. The last Prime Minister to sit in the House of Lords, he had presided over an unparalleled expansion of the British Empire. He died in the following year, and with him a certain aloofness of spirit, now considered old-fashioned, passed from British politics. All the peace terms were kept, and Milner did much to reconstruct South Africa. Nearly half a million British and Dominion troops had been employed, of whom one in ten became casualties. The total cost in money to the United Kingdom has been reckoned at over two hundred and twenty million pounds.

We have now reached in this account the end of the nineteenth century, and the modern world might reasonably have looked forward to a long period of peace and prosperity. The prospects seemed bright, and no one dreamed that we had entered a period of strife in which command and ascendancy by a single world-Power would be the supreme incentive. Two fearful wars, each of about five years’ duration, were to illustrate the magnitude which developments had reached during the climax of the Victorian era. The rise of Germany to world-Power had long been accompanied by national assertiveness and the continuous building up of armaments. No one could attempt to measure the character and consequences of the impending struggles. T o fight on till victory was won became the sole objective, and in this the power of the nations engaged was to prove astounding. It seemed so easy in the course of the closing years of the passing century to take as a matter of course the almost universal system of national armies created by general conscription and fed by the measureless resources of industrial progress. Order and organisation were the salient features of modern life, and when Germany threw all her qualities into the task the steps became obvious, and even inevitable. Nay, it could be argued, and perhaps even proved, that the wise and normal method of modern progress, which all the Continent of Europe adopted in one form or another, was the principle of rearmament on the highest scale. Such was the vitality of the human race that it nevertheless flourished undeterred.

Alone of the Great Powers of Europe, which ordained that every man should be trained as a soldier and serve for two or even three years, Great Britain availed herself of her island position and naval mastery to stand outside the universal habit—for such it had become. And yet this abstention was by no means to allay the growth of the danger. On the contrary, in South Africa Britain took, unconsciously no doubt, a leading part in bringing about the crisis. She exhibited herself to all the nations as supreme. For three long years the process of conquering the Boers continued, leaving the rest of Europe and America the facts of Empire and much else to meditate upon. All the Powers began to think of navies in a different mood. Germany saw that her world preponderance would not be achieved without warships of the greatest strength and quality, and France and other nations followed her example. It was indeed a new outlet for national pride and energy, of which Japan, at the opposite side

Of the globe, took eager advantage. To the vast military staffs were added naval formations which pointed out the logic and importance of all their doings. The conquest of the air was also on the way. Britain would have been content to rule alone in moderation.

Nearly a hundred years of peace and progress had carried Britain to the leadership of the world. She had striven repeatedly for the maintenance of peace, at any rate for herself, and progress and prosperity had been continuous in all classes. The franchise had been extended almost to the actuarial limit, and yet quiet and order reigned. Conservative forces had shown that they could ride the storm, and indeed that there was no great storm between the domestic parties. The great mass of the country could get on with their daily tasks and leave politics to those who were interested as partisans without fear. The national horse had shown that the reins could be thrown on his neck without leading to a furious gallop in this direction or that. No one felt himself left out of the Constitution. An excess of self-assertion would be injurious. Certainly the dawn of the twentieth century seemed bright and calm for those who lived within the unequalled bounds of the British Empire, or sought shelter within its folds. There was endless work to be done. It did not matter which party ruled: they found fault with one another, as they had a perfect right to do. None of the ancient inhibitions obstructed the adventurous. If mistakes were made they had been made before, and Britons could repair them without serious consequences. Active and vigorous politics should be sustained. To go forward gradually but boldly seemed to be fully justified.

The United States remained, save in naval matters, largely aloof from these manifestations. Her thoughts were turned inwards on her unlimited natural resources, as yet barely explored and still less exploited. Her population still owed much of its amazing increase to immigrants from Europe, and these, out of temper with the continent of their origins and perhaps misfortunes, had no wish to see their new home entangled in the struggles of the old. The vast potentialities of America lay as a portent across the globe, as yet dimly recognised, save by the imaginative. But in the contracting world of better communications to remain detached from the preoccupations of others was rapidly becoming impossible. The status of world-Power is inseparable from its responsibilities. The convulsive climax of the first Great War was finally and inseparably to link America with the fortunes of the Old World and of Britain.

Here is set out a long story of the English-speaking peoples. They are now to become Allies in terrible but victorious wars. And that is not the end. Another phase looms before us, in which alliance will once more be tested and in which its formidable virtues may be to preserve Peace and Freedom. The future is unknowable, but the past should give us hope. Nor should we now seek to define precisely the exact terms of ultimate union.

ENDNOTES

1 The Oxford History of the United States (1927), vol. i, p. 391.

1 The Growth of the American Republic, vol. i, p. 246.

2 Morison and Commager, Growth of the American Republic, vol. i, p. 622.

1 I was returning from a visit to Cuba via America at this time and remember vividly looking at ships off the English coast and wondering which one would be our transport to Canada. W. S. C.

World History

World History