There is no mention of stirrups in the chapter the author of the Strate-gikon dedicated to “Scythians, that is Avars, Turks, and others whose way of life resembles to that of the Hunnish people.”21 Moreover, one of the two mentions of stirrups in the Strategikon has nothing to do either with mounted shock combat or with the Avars:

To make it easier for the corpsmen and the wounded or fallen to mount

The rescue horses, they should place both stirrups on the left side of the saddle, one to the front, as is customary, the other behind it. When two want to get up on the horse, the corpsman and the man who is out of action, the first mounts by the regular stirrup to the front, the other by the one to the back.22

But when the author of the Strategikon has recommendations to make for the organization and equipment of the Roman cavalry troops, he leaves no doubt as to the source of inspiration for his advice:

The horses, especially those of the officers and the other special troops, in particular those in the front ranks of the battle line, should have protective pieces of iron armor about their heads and breast plates of iron or felt, or else breast and neck coverings such as the Avars use. The saddles should have large and thick cloths; the bridle should be of good quality; attached to the saddles should be two iron stirrups, a lasso with thong, hobble, a saddle bag large enough to hold three or four days’ rations for the soldier when needed. There should be four tassels on the back strap, one on top of the head, and one under the chin. The men’s clothing, especially their tunics, whether made of linen, goat’s hair, or rough wool, should be broad and full, cut according to the Avar pattern, so they can be fastened to cover the knees while riding and give a neat appearance [emphasis added].23

Even though the stirrups are not specifically attributed to the Avars, they are mentioned in a passage marked by at least two direct references to Avar practices. This is in fact a chapter of the Strategikon in which its author insists that Roman cavalrymen employ a number of devices, all of which are said to be of Avar origin: cavalry lances, “with leather thongs in the middle of the shaft and with pennons”; round neck pieces “with linen fringes outside and wool inside”; horse armor; long and broad tunics; and tents, “which combine practicality with good

21

22

Strategikon 11.2, English translation in Dennis 1984, 116-18. Strategikon 2.9, in Dennis 1984, 30.

Strategikon 1.2, in Dennis 1984, 13.

Appearance.”936 In this context, the mention of pairs of stirrups to be attached to saddles must also be interpreted as a hint to Avar practices. After all, cavalry lances, horse armor, and tents are also attributed to the Avars in the chapter “dealing with Scythians,” from which stirrups are nonetheless absent. If this interpretation is correct, then the Avars whom the Roman cavalrymen were supposed to emulate must have known the stirrups for some time prior to the date at which the author of the Strategikon wrote about them.

On the basis of a number of chronological references in the text, especially to the battle of Heraclea in 592, some have argued that the Strategikon must have been written during Emperor Maurice’s last regnal years (592-602) or during the first years of Phocas’s reign.937 However, it is difficult to believe that the recommendation the author gave to the Roman army about winter campaigning against the Sclavenes could have been given, without any qualification or comment, after the mutiny of 602, for which that strategy was a key issue.938 The Strategikon must therefore be dated only to the reign of Maurice, namely after 592 and before 602.939 Whether or not the Strategikon is in fact the adaptation of a much earlier work by a late fifth-century writer known as Urbicius, as some have recently proposed, both the “Avar chapter” and the references to stirrups most certainly belong to the latest phase of redaction to be dated between 592 and 602.940 The stirrups in use among Avar mounted warriors, whom Roman cavalrymen were supposed to emulate, must therefore have already been in existence for some time during the late 500s. However, on the basis of the existing evidence, it is impossible to decide for how many years could the Avars have employed stirrups, prior to the author of the Strategikon recommending their use to Roman cavalrymen.

At a quick glimpse, the archaeological evidence does not seem to support the conclusion drawn from the analysis of the Strategikon.

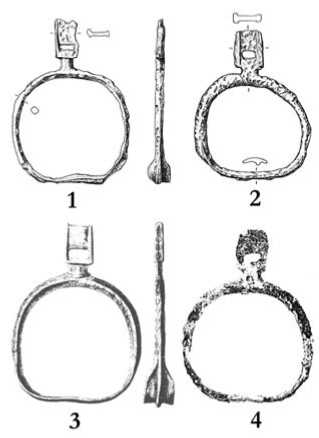

Figure 1. Early Avar-age, apple-shaped cast stirrups with elongated suspension loop and flat tread slightly bent inwards: 1—Budenheim (near Wiesbaden, Germany), horseman burial; 2—Regensburg-Bismarckplatz (Germany), horse burial; 3—Bicske (near Tatabanya, Hungary), stray find; 4—Varpalota (near Veszprem, Hungary), warrior grave 218. After Kovrig 1955, Erdelyi and Nemeth

1969, and Oexle 1992.

No stirrups have so far been found that could be dated to the earliest Avar age, namely between 568 and 600.941 To be sure, round, appleshaped, cast stirrups with elongated suspension loops and flat treads slightly curved inwards have long been recognized as some of the earliest artifacts found in Avar-age assemblages (Figs 1-2).942 Equally early are considered to be the stirrups with circular bow and eyelet-like suspension loop. While by 650, the former seem to have already gone out of fashion, the latter remained in use throughout the seventh century and can even be found in assemblages dated to the early eighth century.943 Two stirrups with elongated suspension loops have been found in association with Byzantine gold coins struck for Justin II (Szentendre) and Maurice (Nylregyhaza-Kertgazdasag), respectively.944 Could those stirrups therefore

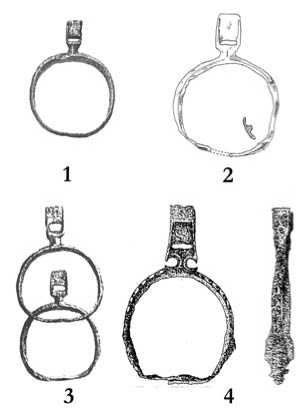

Figure 2. Early Avar-age, apple-shaped cast stirrups with elongated suspension loop and flat tread slightly bent inwards: 1—Selenca (near Novi Sad, Serbia), sacrificial pit; 2—Kornye (near Tatabanya, Hungary), grave 134; 3—Veszprem-Jutas Seredomb (Hungary), warrior grave 173; 4—Zaporizhzhia-Voznesenka (Ukraine). After Csallany 1953, Salamon and Erdelyi 1971, Rhe and Fettich 1931, Grinchenko 1950.

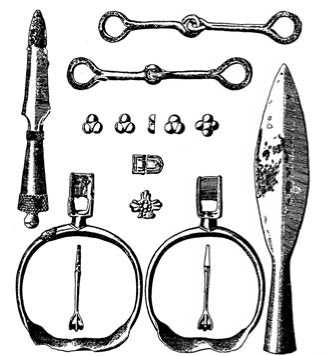

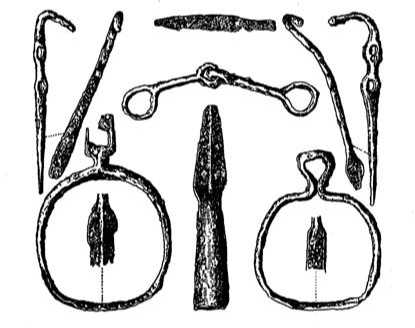

Be coin-dated to the late sixth century? In my opinion, the answer must be negative for a variety of reasons. First, in both cases, the coins were somewhat worn, which suggests that they had been in circulation for some time before entering the burial deposit.33 Second, although occasionally found singly, Early Avar-age stirrups often come in pairs, usually of similar, but sometimes also of different types.34 Stirrups with elongated suspension loops sometimes appear in association with stirrups with eyelet-shaped suspension loops, which are otherwise coindated only to the seventh century (Fig. 3).35

II in Constantinople between 565 and 578. The Nyiregyhaza stirrup was found together with a light (23 carat-) solidus struck for Maurice in Constantinople between 584 and 602. See Somogyi 1997, 67 and 87.

33 In addition, the Nyiregyhaza coin was twice perforated, no doubt to be used as pendant. Almost all coins of Justinian, Justin II, and Maurice found in Early Avar-age burial assemblages are worn. The earliest coin that looks freshly minted is that struck for Phocas and found in grave 3 in Szentendre, followed by gold coins struck for Hera-clius and Heraclius Constantine (grave 29 in Kolked-Feketekapu A; grave 5 in Szegvar-Sapoldal; and grave 759 in Budakalasz). See Somogyi 1997, 32, 55, 85-86, and 88.

34 Stirrups with elongated suspension loop were found singly in Budenheim (Oexle 1992, 203); in the horse grave 40 in Linz-Zizlau (Oexle 1992, 299); in the warrior grave 7 in Dunaujvaros (Garam 1994-1995, 132); in the warrior grave A in Hajdudorog (Kralovanszky 1989-1990, 136); and in the warrior grave 533 in Ciko (Somogyi 1984, 65).

35 Stirrups of both types appear in pairs in grave 70 in Mali Idos (Gubitza 1907, 357-38 and 357 fig. 70); the horse grave 698 in Szekszard-Bogiszlo Street (Rosner 1999,

Figure 3. Baja (Hungary), sacrificial pit: bridle bits, lances, stirrups, and horse gear mounts. After Hampel 1905.

Figure 4. Mali Idos (near Becej, Serbia), warrior grave 70: bridle bit with cheek pieces, knife, lance, and stirrups. After Gubitza 1907.

Nonetheless, there are indications that some, at least, of the specimens with elongated suspension loops may indeed be dated to the late sixth century. To be sure, such stirrups are among the earliest found in 87-88 and 212 pl. 46.698.4/5); Prigrevica (Hampel 1905, 842-43 and 842 fig. 1-2); grave 405 in Kolked-Feketekapu A (Kiss 1996, 113 and 492 pl. 78.A405.4, 5); grave 47 in Budapest-Csepel Haros (Nagy 1998, 160-61 and 118 pl. 110.52.21, 23); grave 218 in Varpalota (Erdelyi and Nemeth 1969, 192 and 194 pl. 23.2, 3). The association is also attested outside the Carpathian Basin, in Voznesenka, an assemblage otherwise dated to the eighth century (Grinchenko 1950, pls. 1.1-4 and 6.9; Ambroz 1982). Stirrups with eyelet-shaped suspension loop have been found together with coins struck for Emperor Heraclius in Hajdudorog, Lovcenac, and Sanpetru German. See Garam 1992, 142-44.

Merovingian assemblages in the Rhineland, which are dated to Ament’s phase AM III (Early Merovingian III, ca. 560/70 to ca. 600) or, more exactly, to the Rheinland Phase 7 (580/90 to 610).945 Inside the Carpathian Basin, a stirrup with elongated suspension loop was found in grave 218 in Varpalota (Fig. 1.4) together with a wheel-made, handled pot of Vida’s class I F/g, dated to the late sixth or early seventh century.946 A variant of the so-called Grey Gritty Ware (Hayes 3), such cooking pots are quite frequent on sixth-century urban and military sites in the northern Balkans, including Justinian’s foundation at Caricin Grad (most likely the site of Iustiniana Prima). Moreover, at Stare Kostolac (the site of the ancient city of Viminacium), they appear in association with wheel-made pottery with stamped decoration dated to the first two thirds of the sixth century.947 No evidence exists so far that pots of Vida’s class I F/g were still in use during the early seventh century. However, since occupation on many of the sites on which such pots were found continued into the 610s, it is at least theoretically possible to date the Varpalota burial assemblage shortly after 600.

The evidence of stirrups in the early Byzantine Balkans is similarly ambiguous. A “stirrup” found in Caricin Grad is in fact a mounting device, whose function was not unlike that of the stirrups early Byzantine corpsmen attached to the front and back of their saddles in order to transport the wounded on horseback.948 A fragmentary stirrup was found together with a cast fibula with bent stem and a three-edged arrow head in a house within the early Byzantine fort at Rupkite, near Karasura (Bulgaria).949 Whether or not the stirrup in question had an elongated suspension loop (a question, which, in the absence of any published illustration, will remain unanswered), the associated artifacts, and especially the cast fibula with bent stem, strongly suggest a late sixth-century date. If anything, the Rupkite stirrup supports the conclusion drawn from the analysis of the Strategikon, according to which stirrups may have been in use in the Roman army before 600. Similarly, archaeological contexts such as those of the Budenheim and Varpalota burials substantiate the idea that before being adopted by the Roman cavalrymen, stirrups had already been known for some time to Avar horsemen.

Although not definitive, the evidence of pre-seventh-century stirrups in Europe is further confirmed by finds from the Middle Volga region, in which stirrups appear already in the late fifth and early sixth century. A stirrup with elongated suspension loop was found in a burial assemblage in Burakovo (near Samara, Russia) together with a double-edged sword and belt mounts with open-work decoration known as “Martynovka mounts,” which are dated to the second half of the sixth or to the early seventh century.950 In this context, the Early Avar-age stirrups from Hungary do not appear any more as the earliest in Europe.951 However, combined with the absence of any other finds of stirrups with elongated suspension loops from the entire area between the Middle Volga and the Middle Danube, a region otherwise rich in late sixth - and early seventh-century finds,952 the presence of slightly earlier specimens in Eastern Europe may support the old idea that responsible for the introduction of the stirrup into Central Europe was the migration of the Avars and other nomads into the Carpathian Basin.953 The only other area in Eurasia with stirrups with elongated suspension loops is that of the present-day Altay Republic at the border between Russia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia. Burial assemblages from that region, which have been attributed to the Turkic qaganate, have produced stirrups with both elongated and eyelet-shaped suspension loops.954 However, the archaeology of the Turkic qaganate era notoriously lacks any firmly established chronological system. As a consequence, there is so far no possibility of deciding whether or not the stirrups found in the Altay ante-date those of the Middle Volga or Middle Danube regions.955

An early seventh-century date is secured for most Hungarian finds of stirrups with elongated suspension loops. Some of them may even be dated before 600, a hypothesis that needs further archaeological confirmation, but which is otherwise not contradicted by the analysis of the Strategikon. Furthermore, the existing evidence does not invalidate the old idea that the Avars adopted the stirrup from other steppe nomads in Central Asia. Ilona Kovrig has long noted that the stirrups with elongated suspension loops found in the earliest Avar-age burial assemblages in Hungary and the neighboring regions were cast of steel of the highest quality.956 Some were further decorated with damascened ornament (Fig. 1.3). Given that stirrups with elongated suspension loops do not appear either in burial assemblages in Eastern Europe or in later assemblages in the Carpathian Basin, Kovrig suggested that such artifacts had been produced in Central Asia and had been brought into the Middle Danube region by the first generation of Avars. Unfortunately, no metallographic analysis has so far been performed on either Early Avar or Turkic-qaganate-era stirrups, which makes it impossible to confirm or to reject Kovrig’s idea.957 In the meantime, it has also been suggested that the stirrup with elongated suspension loop originated in Byzantium.958 But the absence of any finds comparable to either the Early Avar or the

Turkic-qaganate-era stirrups does not support such an interpretation. The only “stirrup” known so far from the Balkans, that of Caricin Grad, is a very different device, while nothing is known about the exact type of the stirrup found in Rupkite. Even if no chronological relation can be established between the stirrups found in Hungary and those of the Altay region, given the existence of similar finds in the Middle Volga region, it seems so far more likely that the source of inspiration, if not in fact the origin, of the Early Avar stirrups must be sought in Central Asia, not in Byzantium.

World History

World History