By the end of 1351, the Plague had run its course, but it left behind a population change equivalent to that which would occur in the modern United States if everyone in the six most populous states—California, New York, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Illinois—died over a four-year period. Not until 1500, about 150 years after the Black Death, would the European population return to the levels of 1300. All over the continent, farms were empty and villages abandoned, leading to scarcity and higher prices— conditions that sparked a number of peasant revolts.

First came the French Jacquerie (zhah-keh-RHEE) in the spring of 1358. The latter took its name from Jacques Bonhomme (ZHAHK bun-AWM), a traditional nickname for a peasant meaning "John the Good Man," and the rebels collectively called themselves Jacques. In the space of a few weeks, the Jacques gathered support from a range of discontented persons, including even minor royal officials. Their targets were the wealthy

People gather around the bed of a victim dying from the Black Death. The Plague, which struck in the mid-1300s, reduced the population of Europe by at least one quarter.

Reproduced by permission of the Library of Congress.

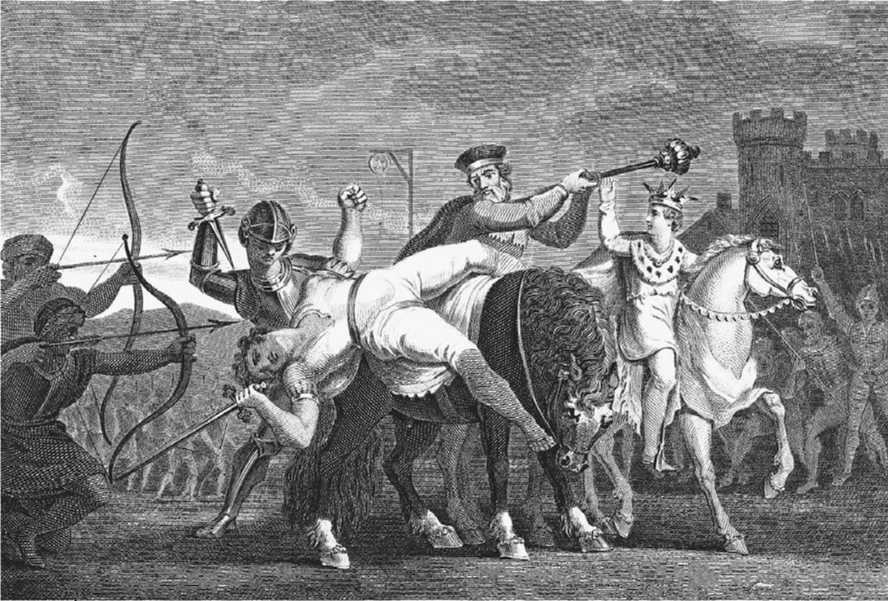

Wat Tyler, leader of a peasants' revolt in England in 1381, is dragged to his death. Reproduced by permission of the Corbis Corporation.

And powerful, and in their furious onslaught, which consumed much of the region around Paris, they did not spare even the children of their enemies. Then, just as suddenly as it began, the Jacquerie was brutally suppressed by the French royalty and nobility, who ordered wholesale executions of peas-ants—many of whom had not even participated in the revolt.

Across the English Channel in 1381, revolts against royal taxation broke out in several English counties, including Essex, Kent, and several others. The most well known of the rebel leaders was Wat Tyler from Kent, who captured the sheriff there and destroyed property records. The Essex force did much the same, then joined the faction from Kent and marched on London to meet with fourteen-year-old Richard II (ruled 1377-99).

Though Richard agreed to meet with the rebels against his advisors' counsel, the government's failure to keep the promises he made them only further enraged the peasants. The rebels destroyed a home belonging to John of Gaunt (1340-1399), Richard's uncle, and killed several of John's advisors. The violence associated with the English revolt, however, did not equal that of the Jacquerie.

World History

World History