All forms of art, from genre painting to landscape tableaux to portraiture, evolved over the course of the 19th century. There was a blending of European artistic styles with uniquely American themes.

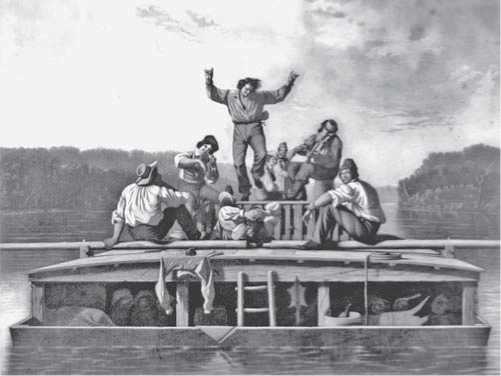

One popular art form was genre painting, which depicted scenes of groups of people interacting in everyday life. The scenes were often comical and sometimes moral and sentimental, featuring portrayals of American stereotypes based on region, race, and gender, such as the crafty Yankee peddler or the hayseed Kentuckian. Artists associated with genre painting included Richard Caton Woodville, George Caleb Bingham, William Sidney Mount, and Lilly Martin Spencer. This art form flourished before the CiviL War but died out after the war when the homey stereotypes no longer rang true. After the Civil War came more-entrenched class, racial, and ethnic divisions. They ceased being comical, and Americans craved more universal images.

Landscape painting also changed over time. Before the Civil War, artists associated with the Hudson River school painted romantic pictures of nature that were rich in shadow and drama. In the landscapes, in the distance, there might be a tiny and solitary person or two overwhelmed in scale by the rendering of the landscape. The paintings

Engraving of flatboat revelers by T. Doney, after the painting by G. C. Bingham (ca. 1847) (Library of Congress)

Were emotive, inspiring awe and a view of God’s presence in nature. Landscape paintings tended to reflect some major themes about Americans’ attitudes toward nature and about the relationship of the individual to God. The landscapes of vast territories also resonated with the ideology of Manifest Destiny. A major artist associated with the first generation of the Hudson River school was Thomas Cole (1801-48).

The second generation of the Hudson River school artists took landscape painting in different directions. Around the time of the Civil War, in a style that is now labeled Luminism, landscape artists tried to present a direct, unmediated portrayal of nature. Some scholars have suggested that Luminism was related to the philosophy of Transcendentalism. Painted on small canvases with shiny surfaces, Luminism emphasized light, horizontal planes and could look almost surreal. Martin Johnson Heade’s (1819-1904) work falls in this category.

Other landscape artists painted in a more naturalistic fashion. For example, Frederic Edwin Church (18261900) attempted to combine scientific truth with a dramatic portrayal of nature. On another front, landscapes of the American West satisfied transatlantic fascination with the land, Native Americans, cowboys, and the like. Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) painted monumental grand landscapes, from the minutest detail to grandeur. George Caitlin (1796-1872) concentrated on Native Americans. Frederic Remington (1861-1909) became known for his epic cowboy paintings.

In portraiture, an artist was usually commissioned to paint an individual or a family. The patron might have wanted a portrait to reinforce his or her social standing or to portray a memory. Before the advent of photography, many artists painted portraits. Painters who often traveled from town to town proliferated as part of a growing material culture in the first half of the 19th century. In the second half of the century, portraits tended to become more restricted to upper-class clients. Thomas Sully (1783-1872) was Philadelphia’s leading portrait painter in the first half of the century, painting more than 2,000 portraits.

Few individual painters are more worthy of note than Thomas Eakins (1844-1916). He realistically portrayed people either in repose or engaged in an activity. Interested in the scientific study of the human form in motion, Eak-ins emphasized the use of nude models and took anatomy classes. His paintings were intense revelations of character. Not a painter of high society, Eakins rarely received commissions and was not distinguished in his own time, although now he is considered one of America’s great portrait painters.

Perhaps the most famous artist of the 19th century was Winslow Homer (1836-1910), known for his freshness of observation and unsophisticated style. Starting with his early paintings—bucolic scenes of rural life and recreation—he rose to prominence as an illustrator and a painter of Civil War soldiers and Union camp life. Beginning in the 1880s, Homer grew progressively more serious in outlook and somber in color. His dramatic and heroic paintings portrayed a Darwinian contest of man against nature, most often in the form of a stormy sea. His view of nature as a source of elemental danger differed from the attitudes of early landscapists, for whom nature evoked reverence and awe.

As the influence of modernization began to be reflected in the paintings of Winslow Homer and others, so too was the influence of European artistic currents. Throughout the 19th century, many artists made trips abroad to study the old masterpieces and learn contemporary styles. When the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art both opened in 1870, a large portion of the work exhibited was European. Some American artists, such as Mary Cassatt and James McNeill Whistler, worked entirely within a European framework, and John Singer Sargent’s work reflected international inclinations.

See also FASHION.

Further reading: Barbara Groseclose, Nineteenth Century American Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); David Lubin, Picturing a Nation: Art and Social Change in Nineteenth Century America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1994); Barbara Novak, American Painting in the Nineteenth Century: Realism, and the American Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1979).

—Jaclyn Greenberg

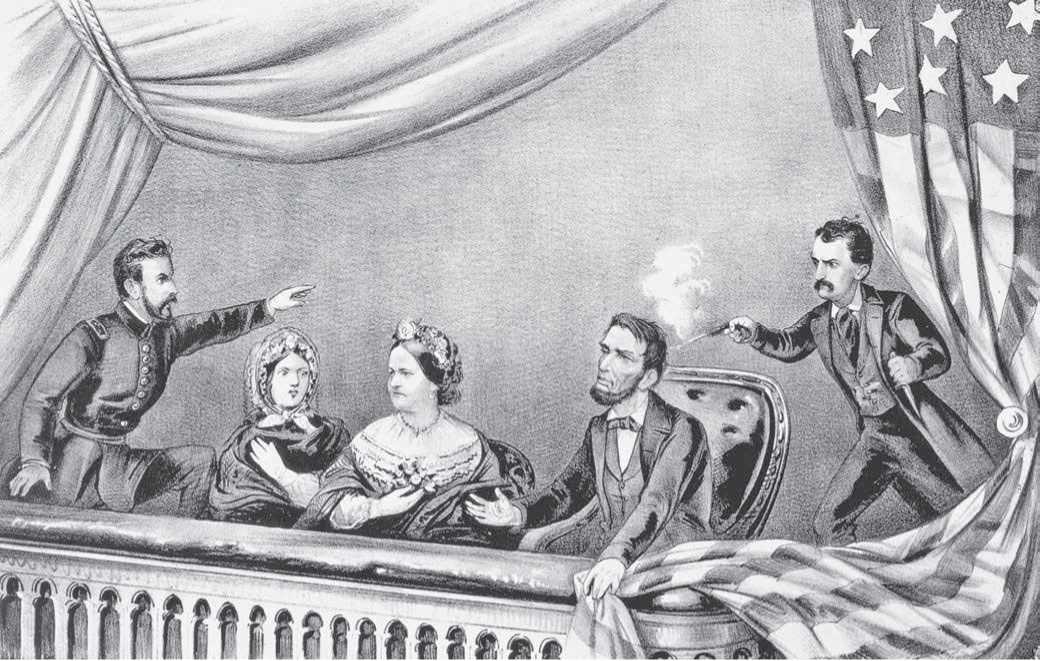

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (April 14, 1865) “Sic semper tyrannis!” These words, which translate as “thus always to tyrants,” were spoken by Brutus as he assassinated Julius Caesar in the play by William Shakespeare. When the famous actor JOHN WiLKES BOOTH shouted the phrase after leaping to the stage during a Ford’s Theatre performance of Our American Cousin on April 14, 1865, most of the audience assumed he was part of the cast. It was not until he had disappeared into the wings that it became clear that he had just shot President Abraham Lincoln.

The notion of Booth as an assassin was shocking to those in the audience that night, many of whom had seen him perform on that very stage. Indeed, the idea might even have been shocking to Booth himself in the early years of the Civil War. A Marylander, Booth was pro-Southern from the outset, describing SLAVERY as “a blessing.” In the early years of the war, however, he was not especially devoted in his commitment to the Confederacy. In deference to his mother’s wishes, he did not enlist in the army, and his actions on behalf of the cause were largely limited to occasional smuggling of medical supplies from the North to the South.

Over time, Booth’s militancy grew, as did his desire to do something dramatic to help the sagging fortunes of the Confederacy. Finally, in the summer of 1864, Booth came up with a plan. During the summer months, WASHINGTON, D. C., was hot, humid, and filled with mosquitoes. To escape the miserable climate, President Lincoln was in the habit of spending his nights at the Soldiers’ Home on the outskirts of the city. Booth hoped to capture Lincoln during one of these trips and take him hostage. In addition to creating chaos in the North, Booth’s hope was that he could exchange Lincoln for Confederate prisoners of war, who were no longer being exchanged for Union prisoners as a result of an April 1864 order by Gen. ULYSSES S. Grant.

Booth knew he needed accomplices, so he recruited two childhood friends, Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlin. They readily agreed, and Booth began his scheming in earnest. He also began to scout out escape routes through southern Maryland. In December 1864 he met John Surratt, who would prove to be a valuable ally. Surratt, like Booth, was engaged in smuggling on behalf of the Confederacy, and he was intimately familiar with the terrain between Washington, D. C., and Virginia. He was also in contact with a network of pro-Southern sympathizers, including David E. Herold and George Atzerodt, both of whom quickly agreed to join the conspiracy. The number of participants grew to seven in March 1865, when Booth enlisted escaped prisoner of war Lewis Powell, who preferred to use the alias Lewis Paine. Booth even went so far as to arrange to have his $15,000 theatrical wardrobe transported to the South, making the assumption that he would resume his acting career after the kidnapping.

After more than six months of effort, Booth had made all the necessary arrangements for the kidnapping plot, and he had all the men he needed. By this time, however, summer was long over, and the president no longer traveled back and forth to the Soldiers’ Home. Other attempts to catch the president while he was vulnerable came to nothing. And so, toward the end of March 1865, Booth gathered his coconspirators and proposed a new plan, wherein the president would be kidnapped while watching a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. The idea was not well-received because the odds of all seven men escaping successfully were very low. Booth was unwilling to budge, and Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlin, and John Surratt left the group.

Without enough men to pull off a kidnapping, Booth began to get desperate. On April 3, 1865, the Confederate government fled Richmond, which meant that there was nowhere to hold Lincoln hostage even if he were kidnapped. On April 9, the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered, and Booth knew that time was quickly running out for him to put a stop to Lincoln’s “lawless tyranny.” On the morning of April 14 he heard that the president would

Engraving showing the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theatre (Hulton/Archive)

Be at the THEATER that evening. It was Good Friday. Booth concluded that this was his last chance and that, since he lacked the resources for a kidnapping, he would have to resort to murder.

Booth still had three coconspirators left, and he found roles for them to play on the evening of April 14, although he did not tell them until 8:00 p. M. that evening, two hours before they were supposed to carry out their assignments. Atzerodt was instructed to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, while Paine was supposed to take the life of Secretary of State William H. Seward. Herold, meanwhile, was responsible for helping the mentally retarded Paine find his way out of Washington. In the end, neither Paine nor Atzerodt was successful. Paine inflicted several serious stab wounds on Seward but failed to kill him, while Atzerodt lost his nerve and never made an attempt to kill Johnson.

After giving Atzerodt, Paine, and Herold their assignments, Booth headed over to Ford’s Theatre. He had no difficulty gaining access to the president’s box, aided by his celebrity as an actor as well as lax security. Though Lincoln had received many threats on his life, there were few precautions taken to ensure his safety. In part, this was because an earlier attempt to protect the president’s life—by sneaking him into Washington before his inauguration—had caused a great deal of political embarrassment. And in part it was because Lincoln felt that such protection was impractical.

Lincoln did have a personal bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, but at Lincoln’s request Lamon traveled to Richmond on the night of April 14. Mary Todd Lincoln selected a temporary replacement from the ranks of the Washington, D. C., police department, John H. Parker. Parker had a poor record and had a reputation for laziness. Shortly after the play started, he abandoned his post to watch the performance. Booth proceeded without challenge to the president’s box.

Observing Lincoln through a hole he had drilled in the door of the president’s box earlier in the day, Booth waited for the big laugh coming at the beginning of the third act that would cover the sound of the gunshot. When the moment came, Booth entered the box and shot Lincoln in the back of the head with a single-shot Derringer pistol. He scuffled briefly with Maj. Henry Reed Rathbone, who had joined the president’s party at the last minute when General and Mrs. Grant had decided not to attend the play.

Having slashed Rathbone with a hunting knife, Booth then leapt the 12 feet to the stage, breaking his leg in the process, and made his exit.

After being shot, Lincoln was carried across the street to the Peterson house. Dr. Charles Leale, who had been in attendance at the play, attended Lincoln initially and was eventually joined by several other surgeons, including Lincoln’s personal physician. They all realized there was nothing that could be done. The president faded quickly and died early on the morning of April 15 without regaining consciousness. “Now he belongs to the ages,” said Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.

Booth fled Washington, trying to work his way South, where he felt he would be hailed as a hero. He was badly mistaken. Slowed by his broken leg, Booth was eventually trapped in a Virginia farmhouse. After refusing to surrender, he was shot and killed, never to answer for his crime. A military tribunal tried eight of Booth’s alleged coconspirators. The hastily conducted trial resulted in death sentences for Herold, Paine, Atze-rodt, and Mary Surratt. Four others were sentenced to prison terms. Many people thought the assassination a Confederate plot, funded and supported by Jefferson Davis’s administration. In the years after the trial, some have argued this point of view, with others suggesting that there was a conspiracy within the Union itself. However, no compelling evidence exists linking any person or group to the assassination besides Booth and his three accomplices. Conspiratorial notions nonetheless persist into modern times, as witnessed by the great number of publications on the topic.

The entire nation was shocked by Lincoln’s death, and it triggered an intense period of mourning and solemnity. On April 18, 1865, his body lay in state in the East Room of the White House, and his funeral took place the following day. Thousands of mourners paid their respects there and in the rotunda of the Capitol on April 20. On April 21 the president’s remains were placed on a special funeral train and began the 1,700-mile journey home to Illinois. Scheduled stops in Phieadeephia, New York City, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Chicago were all heavily attended by a grieving public. Lincoln was laid to rest at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois, the first chief executive to die at the hands of an assassin.

The assassination held dramatic ramifications throughout the postwar period. Without the president’s experienced hand, national reconciliation proved difficult. The work of reconstructing the shattered nation was left to Vice President Johnson, who was sworn in as president by Chief Justice Saemon P. Chase several hours after the assassination. Johnson proved to be ill-equipped for the task that Lincoln left behind. His mishandling of the situation led to his impeachment and allowed the Radicae Repubeicans to gain control of Reconstruction policy. The result was a difficult time in the political life of the nation that might have unfolded in a very different fashion if Lincoln had lived. Nearly a century elapsed before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally granted African Americans political rights and freedoms that had proved impossible to secure in the wake of Lincoln’s passing.

Further reading: Timothy Good, We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995); Thomas Goodrich, The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005); Michael W. Kaufman, American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies (New York: Random House, 2004); Elizabeth D. Leonard, Lincoln’s Avengers: Justice, Revenge, and Union after the Civil War (New York: Norton, 2004); Edward Steers, Jr., Blood on the Moon: John Wilkes Booth, Samuel A. Mudd and the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001); James L. Swanson, Manhunt: The Twelve-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killers (New York: HarperPerennial, 2007); James L. Swanson and Daniel R. Weinberg, Lincoln’s Assassins: Their Trial and Execution (Santa Fe, N. Mex.: Arena Editions, 2001).

—Christopher Bates

Atlanta campaign (May-September 1 864)

During the spring and summer of 1864, Union forces under the command of Wieeiam T. Sherman battled to take control of Atlanta, Georgia. On September 2, 1864, the mayor of Atlanta surrendered the city to the Union general. “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won,” exulted Sherman in a TEEEGRAPH to his commander in chief. Sherman’s triumph secured the election of 1864 for Lincoln and the Repubeican Party.

Plans for the capture of Atlanta, the Confederacy’s largest railroad hub, as well as the destruction of Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, were first formulated in February and March 1864. Ueysses S. Grant hoped that the Atlanta campaign, in tandem with Union offensives in Virginia, would ultimately destroy the Confederacy. In Atlanta, the Union planned to tear up Southern railroad lines and cut off all supplies to Confederate troops. Grant left the specifics of each campaign up to the commander assigned to it.

In April, Sherman revealed his plan. He proposed to push Johnston and his soldiers back to Atlanta, cut off all railroad lines, and then force a Confederate retreat and surrender of the city. To achieve these goals, Sherman had by May 1864 assembled a “grand army” of 110,000 men composed of infantry, cavalry, and artillerymen from the Union’s Army of the Cumberland, Army of Tennessee, and

Army of the Ohio. Sherman held another 93,500 soldiers ready for duty at Union posts in Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, and Mississippi. Sherman’s “grand army” would outnumber Johnston’s nearly two to one. Confident in his numerical advantage, Sherman assured Grant of his army’s ability to defeat the Southern troops.

The fight for Atlanta, which would be contested across much of northern Georgia, got underway near Dalton on May 5, when Union skirmishers engaged Confederate pickets. Although some Southern troops successfully held their positions, others had trouble. Johnston’s use of reinforcements ultimately forced the enemy to withdraw temporarily, but the Union troops were not to be deterred. By May 9, Northern forces threatened Johnston from two sides—Resaca and Dalton. Johnston took his forces south to Resaca on May 12 to meet the enemy.

From May 13 to May 15, the two sides engaged each other in the Battle of Resaca. Neither side gained an advantage during the first day of fighting, but on the second day, the Confederates managed to drive the enemy back. However, after hearing reports of Union successes in gaining position, Johnston scrapped his plan of a morning attack on May 15 and instead evacuated his forces to Calhoun and then Adairsville. Casualties at Resaca numbered 5,100 Confederates and 6,500 Federals.

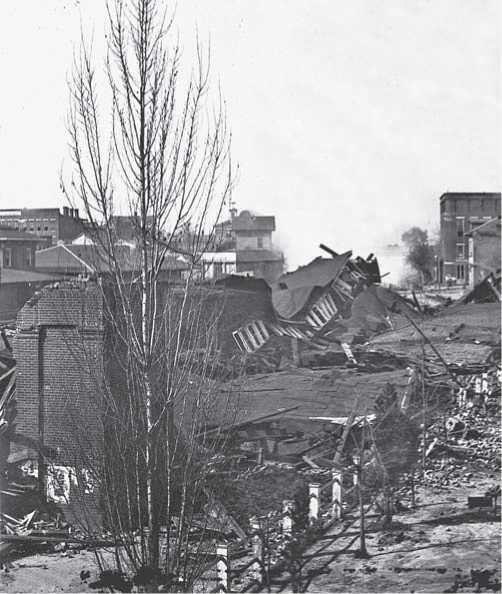

Ruins of a train depot, blown up on William T. Sherman's departure from Atlanta, Georgia (Library of Congress)

After his retreat, Johnston planned to ambush the Federals on the Cassville road. He positioned his troops by early morning May 19, but after Union forces flanked John Bell Hood’s corps, the entire army retreated to wait for a Union attack. When Johnston’s commanders disagreed over the army’s position, the Army of Tennessee evacuated on May 20 to Allatoona, near the Etowah River. Union and Confederate armies met again on May 24 at the Battle of New Hope Church near Allatoona and, on May 28, the Battle of Dallas. The Confederates’ strong defensive position allowed them to drive back five Union attacks and stop Union advances.

By June 4, Johnston and his troops held a strong position in the hills between the Etowah River and Atlanta. They ultimately withdrew about two miles to Kennesaw Mountain, from where they could survey the surrounding countryside and protect themselves from the enemy. Sherman, not deterred by the strength of the Confederate position, launched a full-scale attack on the Confederate lines on June 27. The resulting Battle of Kennesaw Mountain ended in 3,000 Federal and 552 Confederate casualties.

Sherman continued to force Confederate retreats throughout July—to Smyrna on July 3, the Chattahoochee River on July 6, and south of the river on July 9. The retreats would ultimately lead to the dismissal of Johnston as a commander. Throughout the campaign, Confederate president Jellerson Davis and military advisor Braxton Bragg had expressed their lack of confidence in Johnston. In mid-July, frustrated with Confederate retreats and fearful that Atlanta would fall, Davis removed Johnston from his post, giving John Bell Hood command of the Army of Tennessee on July 18.

Hood pursued an aggressive strategy. On July 20, Southern troops launched an unsuccessful attack on Sherman at Peachtree Creek. The unorganized Confederates suffered a high number of casualties during the offensive. Hood launched a second assault, the Battle of Atlanta, on July 22. Again, Southern forces suffered defeat at the hands of their enemies. Hood led yet another unsuccessful attack on the Union troops at the Battle of Ezra Church on July 28. In his short tenure as commander, Hood had lost 17,500 men. He saw no option but retreat into Atlanta, where he and his troops waited for Sherman’s next move.

Union troops laid siege to Atlanta, continually bombarding the city for the next 40 days. The danger scared the city’s inhabitants, many of whom fled. The siege also ended municipal government in Atlanta, with the mayor Thomas Calhoun and the city council meeting for the last time on July 18.

Sherman moved his troops to the south side of Atlanta at the end of August, hoping to cut the last rail line and then lure Confederate troops out of the city. Once Sherman and his men had taken their positions, they ceased firing and waited for the Confederate response. Hood ordered an attack at Jonesboro on August 31, but again Union forces easily defeated the Southern offensive. This was Hood’s fourth and last attempt to protect and hold Atlanta. The series of defeats had resulted in a loss of 25 percent of Hood’s army. The commander evacuated his troops from Atlanta on September 1, 1864.

As they evacuated, Southern troops destroyed any ammunition and military stores that they could not take with them. The next morning, Atlanta’s mayor and a group of citizens officially surrendered the city to Sherman. By noon, Sherman and his troops occupied and controlled the city. The Union occupied Atlanta until November 15, 1864, when they torched the city before embarking on Sherman’s March through Georgia.

See also reeugees.

Further reading: Lee B. Kennett, Marching through Georgia (New York: HarperCollins, 1995); James L. McDonough and James Pickett Jones, “War So Terrible”: Sherman and Atlanta (New York: Norton, 1987); R. McMurry, Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

—Lisa Tendrich Frank

World History

World History