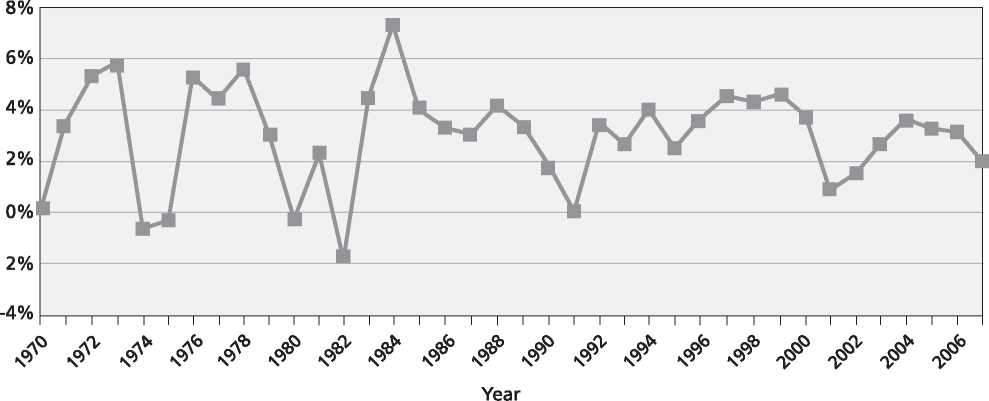

Source: "National Economic Accounts," August 2008, U. S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

@ Infobase Publishing

Were made more severe under laws against racketeering. In 1987 Ivan Boesky was sentenced to three years in prison and fined $100 million. Three years later, in a separate case, Michael Milken, who is still credited with revolutionizing modern capital markets, pleaded guilty to six felony counts of fraud, unrelated to racketeering or insider trading. He was banned for life from securities trading, sentenced to two years in prison, and fined $47 million.

Critics point to the 1980s corporate culture as a “decade of greed” characterized by corporate raiders, leveraged buyouts, insider trading, and sophisticated securities fraud. Business practices, such as securities fraud, undermined confidence in the integrity of financial markets, while leveraged buyouts often left companies with huge debts. Supporters of these mergers noted that the movement forced companies to adjust to modern economic conditions by trimming middle management positions, reducing redundancy, and investing more heavily in research and development to maintain their competitive advantages. Some analysts attribute the stock market’s explosive growth in the 1990s to the added efficiency of large corporations, which they claim provided the venture capital to launch newer technology sectors of the economy. Other analysts doubt the impact of the 1980s business retrenchment on the 1990s boom. Additional tangible results of the market restructuring included the widespread use of consumer credit, the decline of large retail stores, and the rise of discount stores and national retail chains that specialize in one type of product, such as hardware, books, music, toys, or groceries. Whether these innovations represent benefits or detriments to the welfare of society is a matter of opinion.

With the creation of the Internet and the World Wide Web in the early 1990s, the rate of megamergers began to decline, while the rate of small combinations increased. New technology companies rose from obscurity to claim millions of dollars in profits, to be later purchased by a larger corporation. The success of the new technology sector had its own dangers. The Department of Justice and the attorneys general of several states filed an antitrust suit against software manufacturer Microsoft. Microsoft lost its much-publicized case but won an important appeal in late 2001, which resulted in a more favorable settlement offer. After a decade of adjustment to the new technology sectors, the trend toward large corporate mergers continued, as Daimler-Benz joined with Chrysler in a $75 billion merger in 1998, and the Internet service provider AOL joined with media giant Time Warner in a $165 billion merger in 2000.

In 2001 the technology-heavy NASDAQ index fell 40 percent during the first quarter, pulling the Dow Jones Industrial Average down by 10 percent. Some analysts attributed the drop to a shift in demand from personal computers toward alternative wireless technologies as well as unexpected plateaus in returns from electronic commerce. Others described it as a natural market adjustment stemming from the uncritical investment in technology firms that had no real profit potential, but relied instead on inflated confidence in future success. Most analysts remained convinced that the full extent of this technology revolution was still unfolding.

Beginning in late 2001, a series of scandals involving major corporations again shook public confidence in corporate business. The largest scandal involved a Texas-based energy trading firm, Enron Corporation, that reported third-quarter losses of more than $600 million, and its stock price dropped precipitously. Previously ranked among the ten largest U. S. firms, Enron filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December 2001. Filing for Chapter 11 allows a corporation to avoid paying creditors while reorganizing in order to become profitable again. The SEC began an investigation, and in January 2002 the Department of Justice also began investigating for criminal wrongdoing amid reports of document shredding at Enron and its accounting firm, Arthur Andersen.

These investigations and congressional hearings revealed that Enron had accumulated sizable debt that had been hidden through fraudulent accounting practices: The company had overstated its profits; Enron executives had participated in insider trading; and documents had been destroyed. In January 2004 Enron’s chief financial officer, Andrew Fastow, pled guilty to two felony charges; he received a reduced sentence of six years in prison in exchange for testifying against Enron’s former CEO, Jeffrey Skilling, and former chairman, Kenneth Lay. Both Lay and Skilling were convicted in May 2006, but Lay died two months later before being sentenced; Skilling was sentenced to 24 years in prison, but his conviction is under appeal. The accounting firm Arthur Andersen was convicted of obstructing justice by shredding documents.

Enron’s bankruptcy had far-reaching effects. Company employees lost both their jobs and their retirement accounts; many others lost their investments as well. The scandal generated tighter federal regulation of accounting practices. Scandals involving financial mismanagement led to the failures of several other large corporations over the next six months, such as cable corporation Adelphia and telecommunications provider WorldCom, both of which filed for bankruptcy by mid-2002. These scandals undermined investor confidence, which was reflected in stock market drops. In July 2002 the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped to its lowest point in four years. In order to restore confidence, President George W. Bush created the Corporate Fraud Task Force within the Justice Department. Congress enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, creating criminal penalties for corporate fraud and providing oversight of accounting and credit practices. These

Measures appeared to restore investor confidence, as stocks showed a steady rise throughout the Bush administration.

In 2007 mortgage lenders came under scrutiny for questionable lending practices, particularly in the subprime mortgage sector. Subprime mortgages are home loans extended to borrowers with poor credit histories or insufficient income to qualify for conventional loans, who thus pose a higher risk to lenders. The loans are typically adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) that appeal to borrowers because of low initial interest rates but become unaffordable for many as interest rates rise. The borrower who is not able to renegotiate terms faces foreclosure; yet these loans are difficult to negotiate because they are not usually retained by the lending institution but are instead sold off to investors, including foreign investors.

A sharp rise in the number of home foreclosures in 2006 and 2007 caused several lending institutions to file for bankruptcy and adversely affected both U. S. and international investment corporations, thereby focusing attention on lending practices. The Bush administration, while reluctant to bail out irresponsible lenders or borrowers, sought to minimize the effects of the subprime mortgage crisis on the economy. Working with Congress,

Bush sought to expand the government mortgage insurance agency, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), to offer refinanced mortgages to struggling homeowners with good credit histories. Congress conducted hearings to investigate predatory lending practices. When the number of jobs related to the housing industry slumped in August 2007, Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke lowered interest rates several times to head off fears of recession and to stabilize interest rates while struggling homeowners refinanced their mortgages. The housing market remained soft throughout 2007, creating fears of recession. The soft housing market caused a catastrophic financial crisis in late 2008, as home foreclosures spread from the subprime mortgage market to more stable mortgages. Two government-sponsored enterprises, the Federal National Mortgage Association (commonly called Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Mortgage Corporation (referred to as Freddie Mac)—designed to increase or stabilize the housing market by buying up mortgages from lenders and packaging them to sell to investors, thereby keeping capital available for mortgage lending—had run short of capital with which to buy mortgages. Shares of Fannie Mae worth $70 in August 2007 had fallen to $10 a share by July 2008;

Byrd, Robert 61

Freddie Mac shares that sold for $67 in August 2007 were worth only $8 in July 2008. Although technically privately owned, the two companies were bolstered by support from the U. S. government and by October 2008 required government intervention to protect them from bankruptcy.

Many of the largest investment firms on Wall Street, heavily invested in mortgage-backed securities, also began to fail in 2008 because of the mortgage crisis, including Bear-Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and insurance giant American International Group (AIG). Contraction of the credit market left businesses across the country at a standstill, forcing extensive layoffs. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson presented to Congress a proposal for the government to inject $700 billion into the financial sector in order to stabilize a crisis that had become global. In October 2008 Congress passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act that provided a “$700 billion bailout” for financial institutions. Support for this plan was not unanimous, as evident in the House vote of 263-171 and the Senate vote of 74-25. In addition President Barack Hussein Obama signed into law in February 2009 the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a stimulus package designed to encourage job growth through infrastructure projects and investment in “green” technologies such as renewable energy from wind and solar power.

See also crime; economy; Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act; technology.

Further reading: Daniel Fischel, Payback: The Conspiracy to Destroy Michael Milken and His Financial Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 1995); Robert Sobel, Dangerous Dreamers: The Financial Innovators from Charles Merrill to Michael Milken (New York: Wiley, 1993).

—Aharon W. Zorea and Cynthia Stachecki

Byrd, Robert (1917- ) politician

Since his election to the U. S. Senate, Robert Byrd has played an important role as a leader in the Democratic Party. He is the longest serving senator in U. S. history and is considered by many one of the greatest parliamentarians in the history of the Senate.

Born in 1917 in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, he was left a virtual orphan after his mother died when he was one year old. His aunt and uncle raised him in West Virginia, living in various communities in the bituminous coalfields. Unable to afford college, he worked as a gas station attendant, a produce salesman, a meat cutter, and a welder. During World War II, Byrd contributed to the war effort by becoming a welder in wartime shipyards in Baltimore, Maryland, and Tampa, Florida. Byrd then joined the Ku Klux Klan to help win election to the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1946. (He later apologized publicly for his membership in the KKK.)

After serving two terms in the West Virginia House, he was elected to the U. S. Senate in 1959. In 1967 he was selected as secretary of the Democratic conference, and in 1971 as Senate Democratic whip. In 1977 he became Senate Majority Leader, a position he held from 1977 to 1980 and from 1987 to 1988. He was Senate Minority Leader from 1981 to 1986. Because of his parliamentary effectiveness, he played a critical role in shaping major legislation during those years. Although Byrd voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he later endorsed affirmative action and women’s rights. Also, as a leading senior senator, he was able to direct federal funding to his home state of West Virginia for public buildings, state highways, relief for unemployed coal miners, and education.

In 1988 Byrd surrendered Majority Leader status to become chairman of the Appropriations Committee. In 1989 he was elected president pro tempore of the U. S. Senate. His four-volume history of the U. S. Senate received much praise from scholarly critics. As senator, he has been perceived by his colleagues on the Democratic side as a centrist and a statesman.

He is married to his former high school sweetheart, Erma Ora James. They have two daughters, who are now married with children.

Further reading: Robert Byrd, The Senate, 1789-1989, 4 vols. (Washington, D. C.: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1989-94).

—Christopher M. Gray

World History

World History