The West Coast tribes were the great traders of aboriginal Canada. William Brown of the Hudson’s Bay Company called one group, the Babine, “inveterate fishmongers.” Brown’s comment reflects both the frustration and the admiration that many traders felt, a dual attitude that characterized all European trade with West Coast people into the twentieth century. On the one hand, he knew that the Babine, like their neighbours, were tough, sophisticated, highly experienced traders—so much so, in fact, that at times Brown had to resort to strong-arm tactics. On the other hand, he had to admire their ability, and his comment is very much a trader’s observation on other traders.

Brown quickly understood the situation when he told them the prices he was prepared to pay for their large salmon. In response, the Babine “gave us to understand we need not expect any large ones, they being accustomed when people were here en derouin to receive their own prices.” The coast villagers were very much in control. It was they who dictated terms, and once Europeans had arrived on the west coast they struggled to maintain their traditional trading networks by playing one group of

Intruders off against another, whether the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Russians, or the Americans.

Nowhere in Canada was the landscape more diverse or the culture more complex. Food was plentiful. Both trade and food hinged on salmon, although porpoise, seal, sea otter, and whale were taken along the coast, and halibut too. But while all five salmon species were found in abundance on the lower reaches of the rivers near the coast, only the sockeye travelled great distances inland to spawn in the headwaters of the large rivers. So while the coast fishers could usually obtain a catch sufficient to their needs, this was not the case near the headwaters of such major rivers as the Skeena and the Fraser, because the catch depended on the size of the sockeye run. And that uncertainty was compounded hy random fluctuations of the fish runs, often caused by landslides that destroyed fishing sites and altered stream flows. As a result, the Native people of the interior had to rely more heavily on hunting than did their neighbours along the coast.

Salmon were caught in a variety of ways. Nets and fish weirs were the most efficient means where geography permitted; in the narrower canyons, long-handled gaff hooks and dip nets could be more effective. The women processed the fish, preserving large quantities for the winter season by smoking and drying. When, in 1793, Alexander Mackenzie crossed the continent from Lake Athabasca to reach the Pacific, he was welcomed by the Bella Coola. He watched the women preparing salmon, and noted that nothing was wasted:

I observed four heaps of salmon, each of which consisted of between three and four hundred fish. Sixteen women were employed in cleaning and preparing them. They first separate the head from the body, the former of which they boil; they then cut the latter down the back on each side of the bone, leaving one third of the fish adhering to it, and afterwards take out the guts. The bone is roasted for immediate use, and the other parts are dressed in the same manner, but with more attention, for future provision. While they are before the fire, troughs are placed under them to receive the oil. The roes are also carefully preserved, and form a favourite article of their food.

The fattier fish, sockeye, were best suited to smoking, and the leaner ones, chum, were better for drying. Once the processing was completed, the salmon was placed in cedar containers and stored in caches where the meat would be secure from predators.

The eulachon, or candlefish, is an extremely fatty species, and the oil obtained From it was used for both consumption and illumination. The Nass River was the site of the most famous eulachon fishery; West Coast people not only devised a means of extracting eulachon oil, they were also able to package it so well that it could be transported long distances. The result was a widespread oil trade into the interior over mountainous, sometimes treacherous routes that came to be known as grease trails.

The dense rainforest supported relatively little game, but hunting prospects were better inland. In the country bordering the middle and upper Skeena River, the Gitksan (Tsimshian-speakers) and Babine (Athapaskan-speakers) devoted considerable time to hunting the mountain goat, prized for its wool and horns, bear, and beaver, which they valued as a ceremonial food. Beaver, like groundhog, were also hunted for their fur in the Tsimshian area. Because the coastal mountains marked the western limits of the beaver’s range, this was marginal beaver country, and the Indians carefully husbanded the precious resource.

Besides fish and game many varieties of berries were found west of the Rockies. Huckleberry cakes were particularly popular, and they were one of the leading commodities the inland people traded to the coastal villagers. The women made the cakes by drying and crushing the berries, then placing them in a cedar box and boiling them using red-hot stones. The cooked huckleberries were spread on a bed of cooked skunk cabbage or salmonberry leaves arranged over a fencelike cedar drying rack. A low fire burned continuously under the rack until all the berries were properly dried. The women then rolled the berries into a tube, a stick was passed through the centre, and the roll was hung in a warm place until all the berries were completely dry. The rolls were flattened, cut up, and packed in cedar boxes to be traded. When intended for home use, they were left intact.

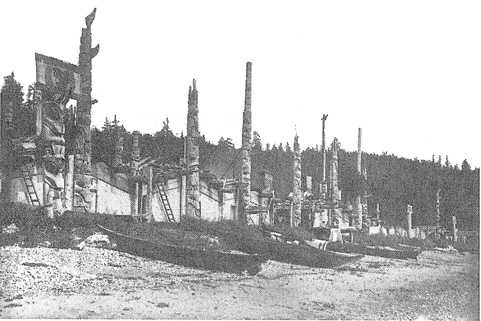

Skidegate Indian Village, Haida Tribe, Skidegate Inlet, Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia, July 1878. By the time G. M. Dawson took this photograph, there were only twenty-five houses (several of them uninhabited) and fifty-three totem poles remaining at Skidegate.

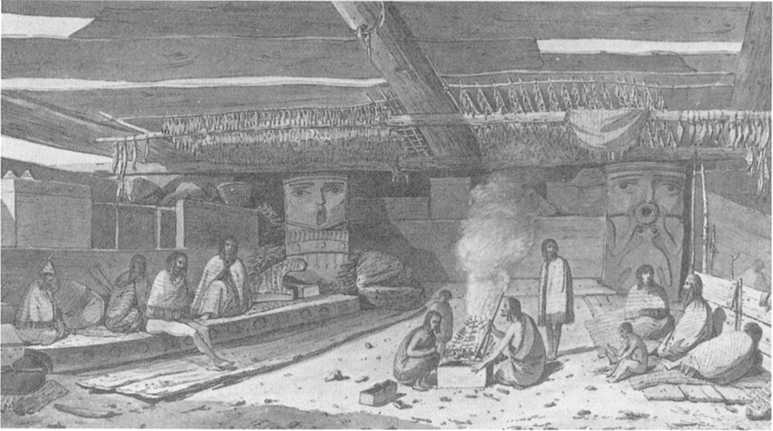

West Coast villagers were the only Canadian Indians to develop the art of weaving—as shown in this monochrome wash and pencil, Interior of a Communal House with Women Weaving, Nootka, April, 1778, by John Webber (1751-92). Webber was a member of James Cook’s crew on the latter’s exploration of the Pacific.

The Aboriginal people of the west coast based their elaborate culture on finely crafted cedar. Certainly they were master woodworkers and their cedar-plank houses were the most substantial and permanent of all the dwellings built by Canadian Native people. Alexander Mackenzie admired the complexity and organization of the houses when he visited the Bella Coola village of Nooskulst (Great Village). The well-built houses were multiple-family dwellings similar to the longhouses of the Iroquois.

The village... consists of four elevated houses, and seven built on the ground, besides a considerable number of other buildings or sheds, which are used only as kitchens, and places for curing their fish. The former are constructed by fixing a certain number of posts in the earth, on some of which are laid, and to others are fastened, the supporters of the floor, at about twelve feet above the surface of the ground: their length is from an hundred to an hundred and twenty feet, and they are about forty feet in breadth. Along the centre are built three, four, or five hearths, for the two-fold purpose of giving warmth, and dressing their fish. The whole length of the building on either side is divided by cedar planks, into partitions or apartments of seven foot square, in the front of which there are boards, about three feet wide, over which, though they are not immovably fixed, inmates of

These recesses generally pass, when they go to rest____On the poles that run along the beams,

Hang roasted fish, and the whole building is well covered with boards and bark, except within a few inches of the ridge pole; where open spaces are left on each side to let in light and emit the smoke.

This coloured pen-and-ink drawing. Interior of Habitation at Nootka Sound, April 1778, is also by John Webber. Note the dried fish hanging from the ceiling, and the way food was roasted over an open fire.

For sea travel, these coastal people built the largest, most finely crafted, and most highly decorated canoes of any Indian group. Alexander Mackenzie described one canoe that he saw as “painted black and decorated with white figures of fish of different kinds. The gunwale, fore and aft, was inlaid with the teeth of the sea otter.” Huge cedar trees were felled (quite an accomplishment considering they had no metal tools) and hollowed out to form canoes from 10.5 to 21 metres (35 to 70 feet) long, some slim and fast for war, some broad in the beam for trade. Packed with provisions and as many as seventy people, these ocean-going craft were capable of coastal trips of several hundred miles. War canoes could be as long as the visiting European sailing ships. Flotillas of these formidable craft full of Native fighters were a sight so daunting that trading vessels routinely dropped anti-boarding nets into place.

Men and women wore cloaks made from skins, strips of rabbit fur, or woven yellow cedar bark. Like their northern neighbours, the Tlingit of Alaska, the Tsimshian wove patterned blankets from the wool of the wild mountain goat, but since it was in relatively short supply and the intricate patterns very difficult and time-consuming to achieve, these blankets were possessed only by the most influential Native people. Indeed, they symbolized high status and became prized articles. For rainy weather, the

West Coast people wove ponchos and conical decorated hats from cedar bark. For cold weather, mittens and cloaks were fashioned from sea otter and other pelts (sea-otter cloaks, like the beaver coats of the northern-forest Native people, were coveted by early European visitors). It is hardly surprising that the most important piece of household furniture was the decorated bentwood box used for storage as well as seating.

As with the Iroquoians, the economic and social organization of West Coast villagers was based on kinship ties of clan and lineage. But the villages acted independently; there was no tribal organization to link one to another as in the case of the Iroquois. Sometimes neighbouring villages worked together or joined forces in battle, but these were purely voluntary joint ventures. Each village, however, contained one or several lineages; and each house within the village contained a lineage, that is, a number of related families. In the north, families traced descent through the female line; in the south, through the male line; and among the central coast Native people, through both lines. The house held the rights to certain fishing sites and hunting territories which were clearly defined, and access was carefully controlled by the head of the house or lineage. Partly for this reason, the first European traders to reach Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en thought of the heads of houses as “men of property.” Indeed, the heads of households not only regulated outsiders’ access to their territories, but also controlled the hunting and fishing activities of their own houses. Among the Babine, William Brown, the Hudson’s Bay trader, estimated that one-half of the adult male population was excluded from beaver trapping by orders of the “men of property.” In this way resources were carefully managed.

Probably the most striking way that their social life differed from that of all other Canadian Aboriginal people was that they had a system of inherited rank, divided into three groups. Chiefs came from the ranks of the nobility; beneath them were the commoners, making up the bulk of the population; and at the bottom were the slaves, who were generally captives or descendants of captives. Social position was determined by ancestry, except for the slaves, whose situation was usually a result of the misfortunes of war. Particular sets of privileges and obligations were associated with inherited titles and positions, and these included the right to use certain symbols in decorative art. Title transfers were publicly witnessed at one of the best known of all North American Native social institutions—the potlatch. Some of these ceremonial feasts were purely for pleasure. Through potlatching, rival chiefs also established new social hierarchies and gained new ranks. During a potlatch the new recipient of a title distributed presents, collected for that purpose with the help of his

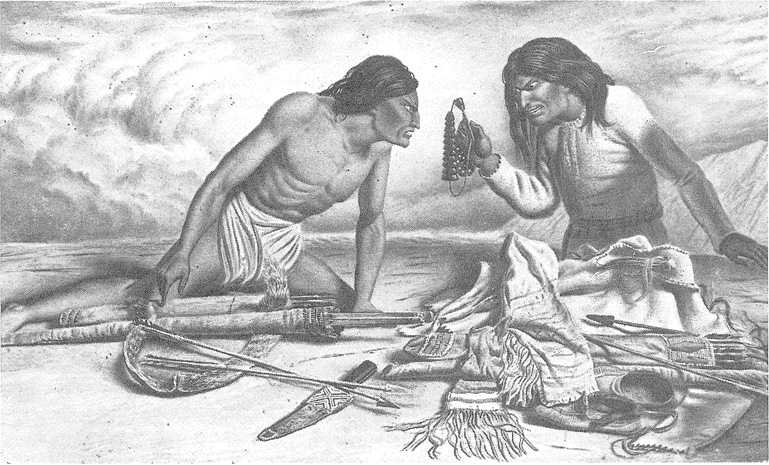

Throughout Canada, Native people were fond of games of chance. Missionaries usually regarded these games as the work of the devil, however, and attempted to ban them. This watercolour. The Game of Bones (1861), is by W. G. R. Hind (1833-88). Hind, who travelled widely in Canada and produced hundreds of paintings and sketches, was the brother of the prolific scientific writer Henry Youle Hind.

Kinfolk, to all the invited guests. The acceptance of gifts by these witnesses to the ceremony was symbolic of their acceptance of the new order; this was particularly necessary in the passing of rights and duties from one generation to another.

Besides playing a central role in maintaining the social order, potlatches served an important economic function. The West Coast people ardently sought wealth to maintain and enhance their social rank. Like the Huron and Plains nations, they used trade as one means to wealth. Possessions obtained through trade, as well as those made locally, were redistributed through the community at the potlatch. Sometimes, too, potlatches were held by members of one village for a neighbouring village which had suffered some economic misfortune, such as a fishery failure.

In the nineteenth century, potlatch ceremonies gained notoriety among the European immigrants, because Native leaders sometimes competed with one another for status through so-called potlatch wars in which one rival attempted to give away or destroy more wealth than his challenger. There is good reason to suppose that potlatch wars were more common after the Europeans arrived, a consequence of the disruption to the Indians’ lives. A “war” could be set off when a village resettled to be closer to a trading post, or as the result of a fatal epidemic, or

Paul Kane made an expedition from Toronto to Fort Victoria in 1846-48; he based this oil painting, Medicine Mask Dance, on sketches done during that trip. Kane recorded in Wanderings of an Artist that the menfolk of the Clallum “wear no clothing in summer, and nothing but a blanket in winter, made either of dog’s hair alone, or dog’s hair and goosedown mixed....” Their mask dance was “performed both before and after any important action of the tribe____”

The increased circulation of European and American goods. Through potlatching, the Native peoples attempted to establish a new social hierarchy.

Along with their love for feasts, coastal people had a great fondness for gambling. Indeed, most of Canada’s Native people had games of chance that they liked to play. According to Hudson’s Bay Company traders, among the Carrier the “game which is most universal consists of about 50 small sticks, neatly polished... of the size of a quill. A certain number of these sticks have red lines around them and as many of them as one player finds convenient are rolled up in dry grasses and according to the judgement of his antagonist respecting their number and mark he loses or wins.” Difficulties often arose when these games were played: “They are addicted to gambling. Umpires are chosen to observe that the parties play fair, but it is seldom terminated amicably.” The stakes of robes, shoes, bows, and arrows, and other possessions were high, and large teams would back the players.

The religious life of the West Coast people was dominated by ceremonies that took place during the winter months. Indeed, among the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl) winter was regarded as the sacred or “secret” season and the rest of the year was considered “profane.” Winter ceremonies were sponsored by the many secret societies—eighteen existed among the Kwakwaka’wakw alone. These societies had strong hierarchies, and members of a given society tended to be of the same gender and social rank. Each society had a mythical ancestor, and its members carefully guarded its secrets. New members, who inherited their positions, were initiated at religious winter dances organized under the careful supervision of a master of ceremonies. Entire villages were invited to watch the dancers performing in elaborate costumes, including carved wooden masks, with a great sense of drama and theatre. These collective rites were unlike the individualistic spirit quests of most Native groups elsewhere in Canada but the goals were similar—to secure the protection of guardian spirits for the individual being initiated.

Besides the elaborate ceremonial aspect of their spiritual life. West Coast people, in a manner similar to Native peoples elsewhere in Canada, engaged in a variety of more simple daily practices and rituals that were intended to show deep respect and appreciation to the spirit world for providing for their basic welfare. Understandably, salmon were particularly revered. When Alexander Mackenzie visited the Bella Coola he was unaware of many of the taboos that had to he rigidly observed. Inadvertently his men violated some of them.

These people indulge in extreme superstition respecting their fish, as it is apparently their only animal food. [Animal] Flesh they never taste, and one of their dogs having picked and swallowed part of a bone which we had left, was beaten by his master till he disgorged it. One of my people also having thrown a bone of the deer into the river, a native, who had observed the circumstance, immediately dived and brought it up, and, having consigned it to the fire, instantly proceeded to wash his polluted hands.

When Mackenzie wanted to obtain a canoe to continue his voyage down the river to the coast, the Bella Coola man he approached kept making excuses. “I at length comprehended that his only objection was to the embarking venison in a canoe on their river, as the fish would instantly smell it and abandon them, so that he, his friends, and relations, must starve.” Once the trader disposed of the venison, he easily obtained the canoe he wanted.

In west coast society, culture, art, and spiritual belief were closely linked. Decoration, whether on the plank prow of a canoe or on such smaller items as tools, household utensils, or containers, served a function beyond the aesthetic. Many decorative motifs were “house” crests, or belonged to a particular lineage that controlled their use. In this, as in so much else that characterized west coast life, the primary intent was the benefit of all members of a lineage.

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)