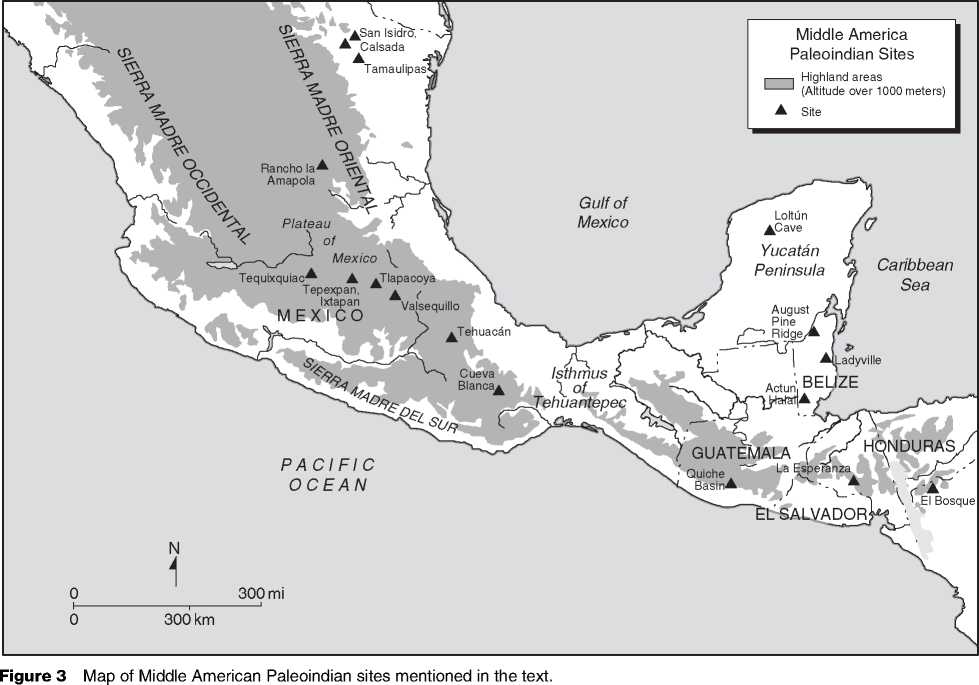

Paleoindian sites in Middle America dating to the earliest time of occupation are scarce, hindered by the fact that population density was low, residence was transitory, and material possessions minimal (Figure 3). Perhaps equally significant, the small number of known sites may be attributed to the relative lack of attention paid to Middle America’s Early Paleoindian prehistory, given the allure of the area’s more spectacular later periods.

One of the best known, though still controversial, Early Paleoindian occupations is located in highland Mexico, near the present-day city of Puebla, where a cluster of what appears to have been transient hunting camps was discovered adjacent to the Valsequillo Reservoir. Excavations at five of the sites, which the investigators designated Hueyatlaco, Tecacaxco, El Mirador, El Horno, and Cualapan, resulted in the recovery of numerous stone tools alongside the fossilized remains of various large, Ice Age animals, including mammoths, mastodons, camels, horses, four-horned antelopes, saber-tooth tigers, and dire wolves.

The Hueyatlaco excavations exposed ten stratigraphic layers of alluvial deposits ranging in age from modern times back to the Pleistocene. Below the top stratum of recent debris were two levels of deposit, the upper of which contained a bifacially flaked stemmed projectile point along with a variety of percussion - and pressure-flaked cutting, piercing, and scraping implements, reflecting a well-developed lithic technology. In association with these implements were abundant bone remains of Pleistocene megafauna.

The lowest artifact bearing ‘unit’ at Hueyatlaco, along with equivalent levels at other Valsequillo sites, revealed a cruder tool-making technology in which fragments were simply smashed off one side of a stone flake to produce a sharp edge that was then marginally retouched by pressure-flaking into an implement of desired form. Along with these tools were the remains of mastodon, camel, horse, and other animals. At the adjacent El Horno site, similar stone tools, some showing signs of use, were found alongside a butchered mastodon. The simple, unifacially flaked

Stone implements, along with the absence of spear or projectile points, are thought by some archaeologists to be part of an early lithic tradition, with roots extending as far back as 40 000 years in time, antecedent to the production of bifacially flaked tools.

Questions arise as to how mastodons, mammoths, and other formidably large animals could have been hunted without projectile or spear points, given the simple stone tools found in the lower levels of the Valsequillo excavations. One explanation is that the early inhabitants and their contemporaries elsewhere in Middle America were foragers whose principal diet consisted of smaller animals and plant foods, the remains of which were not preserved as they were at Monte Verde. Only when a mastodon or mammoth had been handicapped by sickness, injury, or other impediment would it have been pursued. Alternatively, it is possible that the excavations at Valsequillo failed to recover existing evidence of points, or that they had been produced from bone, wood or other perishable materials.

A series of five radiocarbon dates were obtained from fossilized freshwater mollusks recovered from a stream-eroded gully adjoining the Valsequillo Reservoir. The dates, in stratigraphic sequence, span the period from approximately 35 000 years bp at the lowest level to 9150 ± 500 years BP near the surface of the gully. Midway down the stratigraphic profile, a shell sample in direct association with a flake scraper was dated to 21 850 ± 850 years bp, which the investigators proposed as representative of the site’s time of occupation.

In 1962-66, when the Valsequillo project took place, pre-Clovis sites were typically greeted with disbelief. Although that is no longer so, the Valsequillo dates are still considered problematical by many archaeologists on grounds that the shell used for radiocarbon dating is an unreliable medium, and the integrity of the streambed stratigraphy is problematical. A project underway at the Mexican National Institute of Archaeology (INAH) and the National Museum of Anthropology proposes to validate these dates. Other dates from the Valsequillo excavations obtained through an experimental tephra hydration assay of volcanic pumice, from fission track analysis of obsidian, and from uranium series analysis of bone, range from 245 000 to 600 000 years BP and are universally rejected, as they would connote the implausible existence of a New World population antecedent to the evolution of modern Homo sapiens.

In 2005 a British geoarchaeological team working under the shadow of the Toloquilla Volcano, in the vicinity of Valsequillo, announced the discovery of what they claimed to be a large cluster of fossilized human footprints imprinted in volcanic tuff (concretized volcanic ash) at an abandoned quarry. Optically Stimulated Luminescence, a technique that calculates when sediment grains were last exposed to heat or light, was used to date what appeared to be burnt clay fragments within the Cerro Toloquilla tuff, leading to assertions that the footprints were more than 40 000 years old. Later, samples of the tuff were taken to the Berkeley Geochronology Center where they were dated at 1.3 million years BP by 40Argo-n/39Argon and Palaeomagnetic techniques, which would make the ‘Toloquilla footprints’ - if that is really what they are - impossibly ancient.

Another questionable Early Paleoindian occupation in Middle America is the El Bosque site, in Nicaragua, near the southernmost periphery of Middle America. Excavations uncovered crudely flaked stone tools along with mastodon, giant sloth, and horse remains. Radiocarbon dates extend from 18100 to over 35 000 years in the past. One of the lithic implements has been classified a primitive ‘chopper’, a simple bifacial implement type some prehistorians profess to be characteristic of the earliest tradition of New World toolmaking, preceding in time the unifacially flaked tools found in the lower stratigraphic levels at Valsequillo. Doubts have been expressed about the early dates for the site and even whether the lithic finds are actual artifacts.

A more probable Early Paleoindian occupation is reported at Tlapacoya, located near Lake Chalco in highland Central Mexico. Eight seasons of interdisciplinary fieldwork at the site from 1965-73 produced a large number of stone tools, animal bones, and plant remains, some recovered in or around what appear to be ancient hearths. From a suite of radiocarbon determinations, a sample from a circular hearth dated 21700 ± 500 years bp was selected as an indication of the age of the site. Two other cooking areas, replete with the remains of stone tools and animal bones, many from now extinct Pleistocene mammals, suggest a series of temporary campsites along the ancient lakeshore. Many of the artifacts from the earliest dated locality were crudely made flakes and blades similar in form to those from the lowest Hueyatlaco excavation levels. Several bifacially flaked obsidian implements were also found in association with the animal bones and hearths. Remarkably, the nearest source of obsidian is located more than 50 km from the site, indicating that the Tlapacoya hunter-gatherers either ranged widely or had established exchange relationships with adjacent groups. However, the more sophisticated obsidian flaking technique used to produce the implements, atypical of Early Paleoindian toolmaking, raises reservations about their association with the early radiocarbon dates.

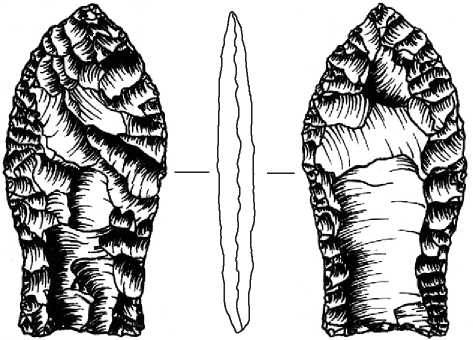

Figure 4 Fluted Clovis point from August Pine Ridge, Belize. Courtesy of Fred Valdez, Jr., drawn by Dee Turman.

2

Also in Central Mexico, the Rancho La Amapola site in San Luis Potosi was, at the time of its occupation, situated in an area resplendent with lakes, marshes, streams, and springs, making it an attractive habitat for humans and other animals. Several seasons of excavation between 1977 and 1980 produced remains of mammoth, mastodon, horse, camel, dire wolf, short-faced bear, glyptodon, giant sloth, and other now-extinct megafauna, but only three definite artifacts: a point carved from a horse tibia, a limestone hammerstone, and a discoidal chalcedony scraper. A charcoal sample from what was believed to be a cooking area was dated at 31 850 ± 600 years bp; another radiocarbon determination from the stratigraphic level in which the scraper was found produced a date of 33 300 ± 2700-1800 years bp.

In the lowlands of Middle America, only two sites, both in caves on the Yucatan Peninsula, offer insights into possible Early Paleoindian occupation. Neither have the confirmation of radiocarbon dating. Loltiln Cave, in the Puuc Hills of northern Mexico, is dated solely by the association of crude stone and bone tools with the remains of mastodon and other Pleistocene age animals in the lowest stratigraphic levels of excavations. Projectile points are lacking. Upper strata have evidence of occupation by pottery-making peoples. Analysis of the stone tools and their faunal association has led to speculation that occupation may extend back in time as early as 40 000 years. Actun Halal Cave in western Belize also relies on the association of stone tools with the remains of extinct megafauna for its Early Paleoindian assignment. Among the lithic artifacts associated with the fragmentary remains of horse, spectacled bear, and peccary are a crude, bifacially flaked cobble, possibly a chopper, and a discoidal-flaked core. The core, however, is reported to be similar to artifacts found in fluted biface assemblages elsewhere in Middle and North America, which would suggest that the site may actually date to the Late Paleoindian period.

World History

World History