The term ‘Indigenous archaeology’ and recognition of the concept are relatively recent developments. The earliest use of the term is in Dewhirst’s 1980 monograph, The Indigenous Archaeology ofYuquot, but this referred to the Aboriginal (vs. European) component of the archaeological site. However, essential aspects of the still-unnamed concept appear in print at least a decade earlier. David Denton’s 1985 statement that ‘‘The development of native archaeologies requires an ongoing dialogue between traditional scientific archaeology and various native perspectives on the past’’ (emphasis added) is one of several that recognized the need for broadening the scope of archaeology.

It was not until the late 1990s that the term was used with some consistency in its modern connotations. The first published definition of Indigenous archaeology is by Nicholas and Andrews (1997) who used it in reference to ‘‘archaeology with, for, and by Indigenous peoples’’. Thereafter, the term appears with increasingly frequency, becoming widespread in 2000 with the publication of Joe Watkins’ volume,

Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian Values and Scientific Practice. Although Watkins did not define the term, his review of the historical development of Indian-archaeologist relations in North America (particularly as related to CRM and to reburial and repatriation issues) contextualized key aspects of the concept. The term has now gained wide recognition, despite the fact that it still resists formal or consistent definition.

The ‘indigenous’ part of Indigenous archaeology most often relates to the involvement of so-called Fourth World and/or formerly disempowered, or disenfranchised, or colonized peoples in the process of doing archaeology (Figure 3). Maybury-Lewis’ definition of ‘Indigenous peoples’ as those who are ‘‘marginal or dominated by the states that claim jurisdiction over

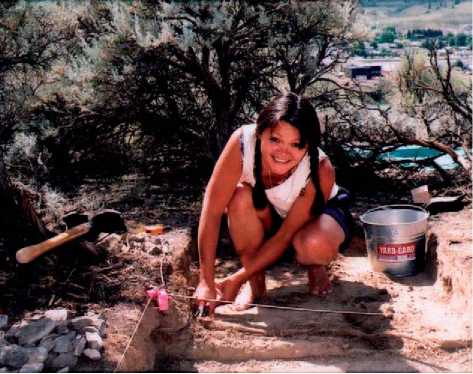

Figure 1 Randi Hillard, Nuxalk First Nation, examining 3000-year-old shell midden at an ancestral Secwepemc archaeological site in Kamloops, British Columbia, 2002 (G. Nicholas, Photo).

Them’’ (2002: 7) generally coincides with how the term is constituted in the present archaeological context. There are, however, indigenes who are not disenfranchised or disempowered; in many parts of Africa, for example, they are the government. Likewise, while archaeology in China has always been ‘indigenous’, that falls outside of the realm of ‘Indigenous archaeology’. In Australia, ‘indigenous archaeology’ most often refers to the archaeology of the pre-contact period.

Indigenous archaeology generally refers to projects and developments associated with or initiated by Aboriginal peoples in the United States, Canada, and Australia, but may include others (e. g., African Americans). However, expressions of Indigenous archaeology also appear widely elsewhere, including in parts of Africa (e. g., South Africa, Kenya), New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, northern Europe, Siberia, and Central and SouTh America. This has created discussion around the questions of ‘‘who is ‘indigenous’?’’ and why some individuals do not consider themselves as such. In Central America, for example, only a small percentage of the native-born population currently self-identifies as ‘indigenous’. This clearly reflects important political and social issues regarding identity and self-representation.

Aspects of Indigenous archaeology may overlap with or be synonymous with ‘native archaeology’, ‘internalist archaeology’, ‘anthropological archaeo-ogy’, ‘collaborative archaeology’, ‘covenantal archaeology’, ‘vernacular archaeology’, ‘community archaeology’, ‘stakeholder archaeology’, ‘participatory action research’, ‘ethnocritical archaeology’, ‘reciprocal archaeology’, and ‘ethical archaeology’.

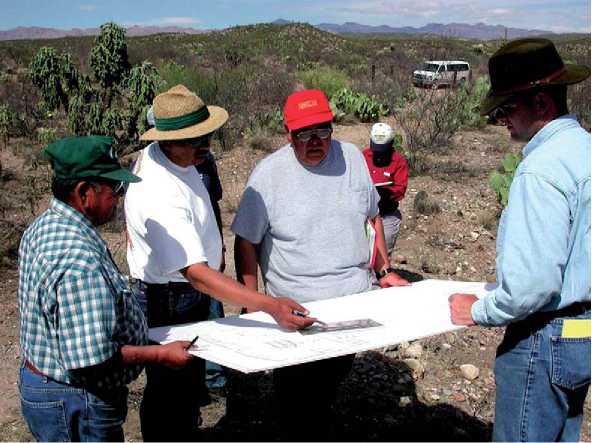

Figure 2 Hopi tribal member LaVern Siweumptewa interpreting a petroglyph map depicting clan migrations at the site of Wupatki in northern Arizona, with Micah Loma’omvaya, Bradley Balenquah, and Mark Elson looking on. Photograph by T. J. Ferguson, July 29, 1998.

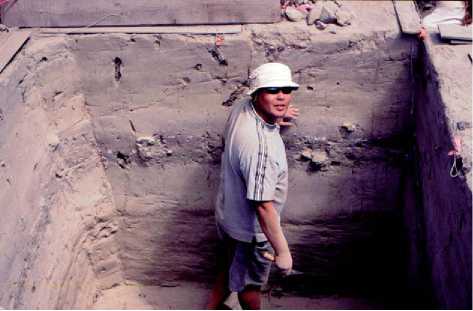

Figure 3 Sharon Doucet, Ehattesaht/Nuu-chah-nulth Nation, British Columbia, represents one of a growing number of Native Americans who see archaeology as a vital bridge between past and present (G. Nicholas, Photo).

World History

World History