The Zulu in South Africa settled in a particularly excellent area for agriculture and herding. Known as Kwazulu Natal, it has three different geographic areas. The lowland region along the Indian Ocean coast with its subtropical climate and the central region of undulating, al-fisol-rich hills rising toward the west, which are perfect for grazing, both with excellent soils. There are two mountainous areas, the Drakensberg Mountains in the west and the Lebombo Mountains in the north with mostly alpine grassland.

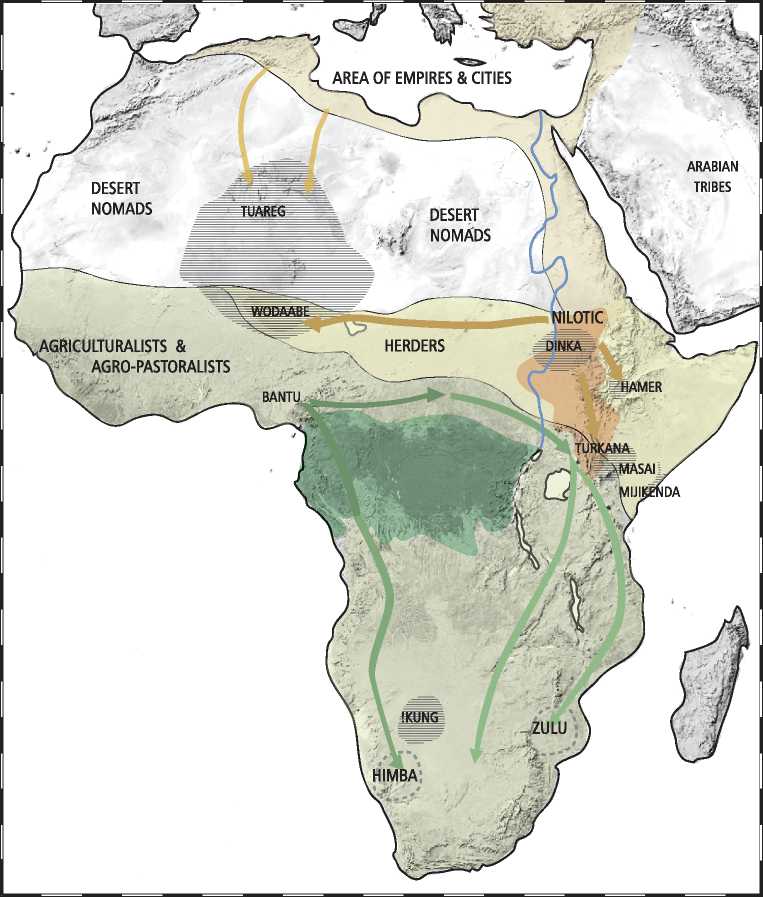

Figure 15.1: Africa and the Bantu expansion. Source: Florence Guiraud

In the Bantu world, every settlement has a court where men meet to discuss political matters and resolve disputes. This court is directly associated with the leader of the settlement and its jurisdiction varies with the leader’s rank and status. This system works its way up to the highest-most chief through at least five levels. Senior leaders used their herds to establish allegiances, making loans and political alliances through the exchange of cattle for wives. Partially because of so many wives, the senior leader had more fields around his capital than anyone else. His court officials included guards, messengers, and councilors.

Status governs the layout of villages. The chief’s courtyard with the cattle pen ws located first. As soon as that was settled, people placed themselves around the circle according to rank. The settlement usually faces downslope so that the residence of the senior man will be upslope behind the court and the ritual rain area still higher. The arc of houses is arranged around a central zone that contains cattle byres, grain storage facilities, elite burials, and the men’s court. There are separate pens for goats, sheep, and lambs. Each village has an entrance with lanes defined by stone walls that steer the cattle to the central space. An ash midden is usually located just outside the village and in the path of the entrance, the ash being thought to purify the animals. The elite graves are placed near the walls of the byre as they form a link through the ancestors to the traditional past. Religious ceremonies of a public nature occur there, such as those associated with sowing, first fruits, and harvest. The court was also placed in proximity to the byres. Men ate there and spent most of the day doing wood-, bone-, and hide-working. Whereas the front of the byre was reserved for public and secular activities, the back was restricted to private sacred and life-giving functions. This was, of course, where the headman lived. The area just behind his residence was reserved for rainmaking rituals. The residential areas consist of a hut with a kitchen in front and an enclosed “backyard.” The kitchen was usually not roofed. The backyard was used for the storage of grain as well as the grave sites of men and women of lower status. It is also used to store ancestral spears. Ancestor spirits are associated with the thresholds of the doorway during group rituals, such as the purification of windows but they are invoked for individual purposes at the back.

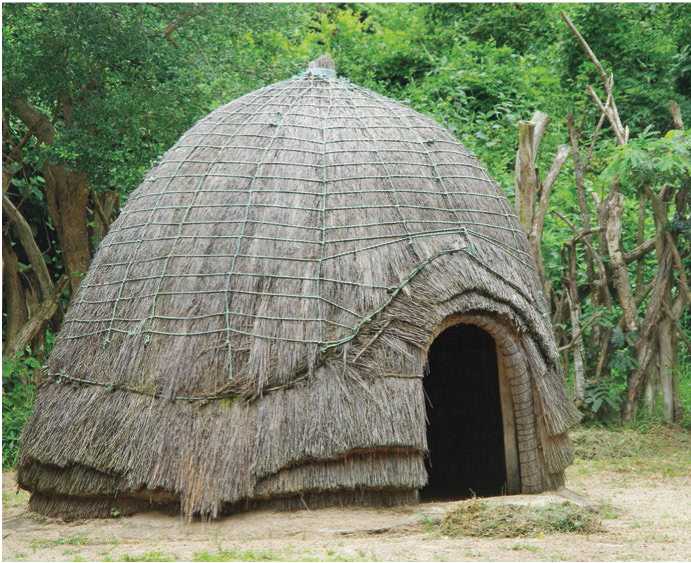

The dome-shaped Bantu huts of the Ngwane Bantu of Natal certainly rank among the finest such structures in Africa. They are built entirely of grass, leaves, and laths. The grasses are gathered by the women in the slopes of the nearby mountains and carried some 4 to 10 kilometers over rugged terrain. It takes about forty days to gather the material. The grasses include long narrow leaves of Hypoxis rigidula; the wide papery leaves of the Curtonus pan-iculata, a thin pale grass that grows in tufi:s next to mountain streams at high altitude; and Phragmites commuis, which grows in swampy areas. Thatch grasses are also collected.1

The laths and poles are collected by the men. Acacia mearnsii, or black wattle, is used, because it is easy to bend, but gray poplar is also used. The 228 laths are sharpened at the bottom end and must be used fresh. The poles are debarked and about 100 meters of lianas (secamone) vines are collected from the forest, which will be used for the door.

Since the Ngwane seldom have fences around their fields, the hut is sited so that it has a good view of the field. Building away from the streams, which can flood, is important in the siting. Each family has its own cluster of huts (umuZi) built around the cattle enclosure. If a new umuZi is to be built, the local headsman allocates land for it, even though the land remains the property of the chief. The hut usually faces the northeast direction or at any rate with its back to the winter winds which blow from the northwest.

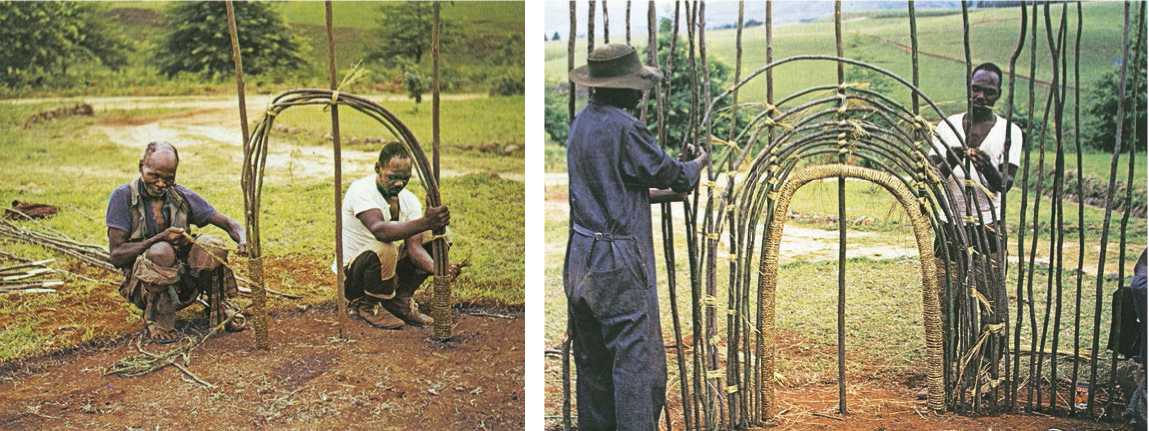

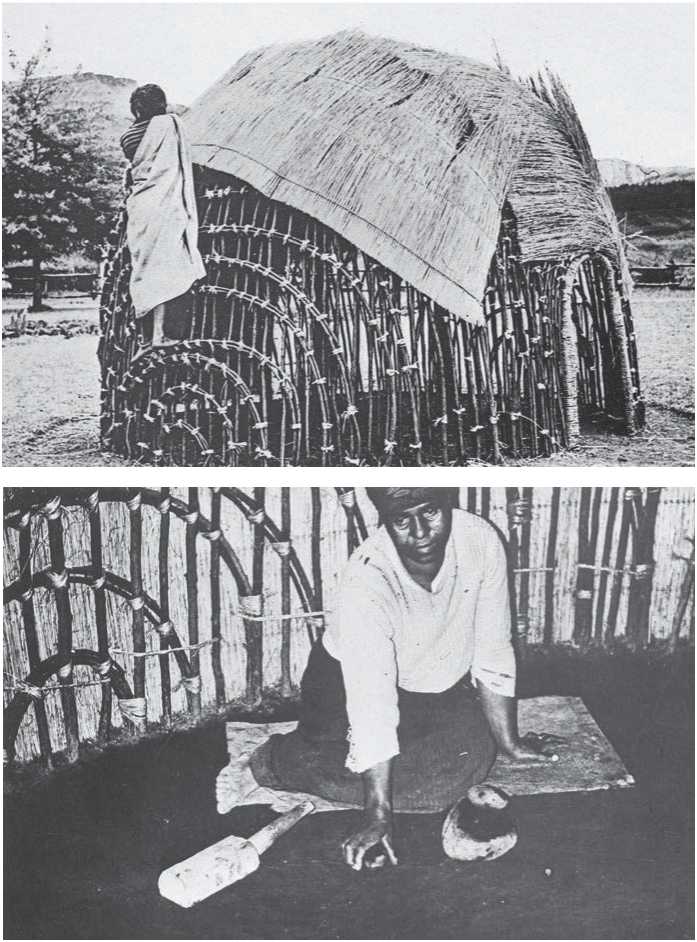

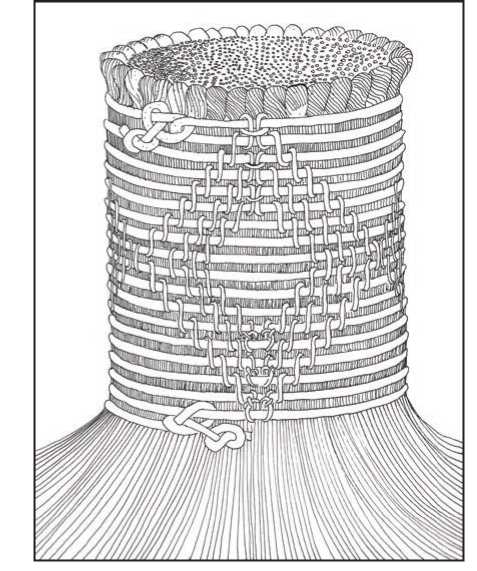

The building of the framework is the duty of the men. A center peg is first driven in the site and a rope attached, which allows a circle to be inscribed. Most huts have a radius of about 2 meters. A cross is then inscribed on the ground. One of the four arms passes through the middle of the proposed doorway. Strong laths are planted into the ground at the four endpoints about 30 centimeters deep. The framework for the door is made with the anchoring lath still blocking its passage. Men plant laths in the circumference of the hut and begin to construct reinforcing arches on the three cardinal sides. These arches unify the structure. The joints are tied together with bundles of grass. Since the door opening interferes with this system, it is given special attention and extra arches are added and secured (Figures 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5). When this is accomplished the hut looks like a circular palisade of upright laths. This tube-like structure is then made into a dome by bending the laths toward the center and tying them up, not radially but from left to right along the axis of the hut, so that the rearmost arches are the shortest, resulting in a structure that can easily support the weight of the various men who are building it. The complete framework, a support structure of poles, is built inside the hut, which will carry the weight of the thatch and lend stability to the hunt during storms. It is not built first but after the framework is done so that it can be custom tailored to the shape of the dome. The structure is then ready for thatching, which will require 400 feet of grass matting made of fine thatch grass. The weaving is complex and a mixture of function and ornament. The difierent mats are stitched to the structure with vine ropes using a large iron needle that is passed from one woman on the outside to another on the inside. At the top of the dome, which is rather flat and thus susceptible to rain seepage, a special mat is placed designed to absorb water. The

A Figure 15.2: Construction of Bantu grass hut, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Source: Werner E. Knuffel, The Construction of the Bantu Grass Hut (Graz: Akademische Druck und Verlags anstalt, 1973), 66

4 Figure 15.3: Construction of Bantu grass hut, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Source: Werner E. Knuffel, The Construction of the Bantu Grass Hut (Graz: Akademische Druck und Verlags anstalt, 1973), 67

Door is constructed of laths and designed to slide sideways. To lock the door a forked stick is wedged between the front center post and the top of the door, the fork resting against the base of the center post. To close the door when everyone is out so that animals do not get in, a loop of rope is tied onto the outside of the wickerwork and a horizontal spar is passed through the loop (Figures 15.6, 15.7).

Once the hut is completed, the top layer of dirt is removed from the hut’s floor and replaced with clayed red soil obtained from weathered dolerite. It is slightly moistened, spread out over the floor and beaten. The flreplace is placed between the center posts. It is oval and has walls running around the outside and a basin-like depression in the center. As the floor dries, it cracks and is repaired until it is smooth. It is then polished until it is quite smooth. Afl:er this the floor is rubbed with a charcoal paste and polished until it becomes a smooth black surface. Since the charcoal would rub os' on skin it is rubbed over with a black plant juice (extracted from the bud of Hypoxis oligotricha), which forms a highly glossy fllm and binds the charcoal to the clay.

The history of the Bantu tradition of painting murals on the walls of their houses is not known with certainty, but scholars suggest that it was flrst practiced by such Sotho-Tswana tribes as the Tlapin, Hurutse, Koena, and Pedi, who live in Botswana and South Africa, and who migrated to the area in the fourteenth century from east Africa. From there the practice spread. The Sotho-Tswana homestead consists of huts set in a courtyard, lapa, bounded by a wall or reed fence. The fronts of the huts, the inside walls, the floor of the lapa, and the wall surrounding the lapa are all decorated with patterns that comprise chevrons, triangles, rectangles, diamonds, and a variety of curved shapes. The drawings are made by the women owners of the house. Animals and other naturalistic subjects are also sometimes depicted. In some cases the walls are etched with grooves made by a flnger or stick. Similar decorative ideas are found among the Dogon and other nearby cultures in Mali and around the bend of the Niger River. It has been suggested that the source might have been the Berbers to the north, with whom the Dogon and others had contact before settling in their current region. In other words, the idea of patterning the walls spread southward in two waves, toward the west and one along the east coast. In some cases the patterning is only applied to the chief’s house or an important wall.2

World History

World History