In the reorganization of commands following the Pearl Harbor attack and the declarations of war. Admiral King was ordered to Washington as Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet (COMINCH). Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll succeeded BCing as Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT). Because Admiral King’s responsibilities were found to overlap those of Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), President Roosevelt, in March 1942, sent Stark to London as Commander, U. S. Naval Forces, Europe, and appointed King CNO as well as COMINCH.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff were Admiral King; General George C. Marshall, U. S. Army Chief of Staff; and General Henry M. Arnold, Chief of Staff of the U. S. Army Air Corps. All were also members, with their British counterparts, of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. In July 1942 Admiral William D. Leahy was appointed to the post Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief of the Army and the Navy, President Roosevelt. In that capacity Leahy was a member of both the Joint and the Combined Chiefs of Staff and was their presiding officer.

For the U. S. Navy, World War II was three interrelated wars, each with its special problems; the war against enemy submarines, known as the Battle of the Atlantic; the war against the European Axis; and the war against Japan. Although these wars were in progress simultaneously, they are treated separately in this narrative for the sake of clarity, in the order given above.

Admiral Karl Donitz, commanding German submarines, was surprised by the Pearl Harbor atfack and

Admiral Ernest J. King.

Therefore did not get U-boats into American waters until mid-January 1942. Even then, he could send only five. These submarines and their successors, never more than a dozen at a time, played havoc with coastal and Caribbean shipping. They sank 26 vessels of 146,000 gross tons in January, 36 ships totaling 192,000 tons in February, and 47 vessels of 276,000 tons in March. Surfacing after dark, the U-boats found targets in ships that were often fully lighted or were silhouetted by shore lights or the glow of brightly illuminated cities. Burning vessels became a familiar sight off East Coast resorts, and the beaches were gradually covered with black oil from torpedoed tankers. This dreadful slaughter of shipping, which the government tried to keep secret, caused a far greater setback to the American war effort than the partly publicized Pearl Harbor attack.

To meet the U-boat onslaught. Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews, Commander Eastern Sea Frontier, had only a handful of patrol craft. Such vessels had been neglected in favor of building larger ships, on the assumption that they could be built quickly enough when needed. In February the British came to the rescue with 24 trawlers and 10 corvettes. As these and other

Patrol craft became available, small, lightly escorted convoys called “bucket brigades” began running along the coast during the daylight hours and putting into protected anchorages for the night. At the same time, for the benefit of faster ships that still ran at night, the government ordered a blackout of waterfront lights and a dimout of all port cities.

By May a regular coastal convoy system was in operation, and nearly 200 planes were on antisubmarine patrol from 19 airfields along the U. S. East Coast. Donitz, retreating before these countermeasures, ordered his U-boats to concentrate in the Caribbean Sea and the Culf of Mexico. Here in May they sank 85 ships, mostly tankers, while only 5 were sunk off the East Coast. As more escorts became available, an interlocking system was established whereby ships could transfer from convoy to convoy in order to serve the complex pattern of shipping in the Gulf and Caribbean. '

The U-boats now retreated to the waters off Panama, Trinidad, Salvador, and Rio de Janeiro in search of unprotected ships. Their stay was lengthened by the presence of new supply submarines known as “milk cows.” The sinking of five Brazilian freighters off Salvador in late summer provoked Brazil into declaring war on Germany. By the end of 1942, convoys were in full operation as far south as Rio de Janeiro, and the U-boats had retreated to the convoy routes of the midAtlantic.

THE TENTH FLEET AND HUNTER-KILLER OPERATIONS

Combatting U-boats was far more difficult in World War II than it had been in World War I. The submarines could no longer be penned in by mines, because Germany early gained control of all the European coast from North Cape to the Pyrenees. They could not be destroyed at their Bay of Biscay bases, because, while the Royal Air Force had been busy protecting England from invasion, the Germans had built on the French coast submarine pens with concrete overheads so thick as to be virtually impenetrable by bombs. The U-boats, moreover, were controlled by the intuitive genius of Donitz, who, using radio, massed them in wolfpacks against convoys and coached them into action.

Convoy continued to be the best means of protecting shipping, although a great deal more was now required. Early in the war the British and Americans operated convoys together, but Admiral King was dissatisfied with the way the Admiralty directed British-American convoys to northern Russia. At his suggestion, the British and Canadians, after March 1, 1943, retained control of the North Atlantic convoys, while the Americans controlled convoys sailing from one American port to another and those in the Central and South Atlantic.

On May 1, Admiral King brought together all American antisubmarine control and intelligence activities into an organization called the U. S. Tenth Fleet. To give the new fleet authority, he himself assumed command, but he delegated operations to the fleet chief of staff. Rear Admiral Francis S. Low. The Tenth Fleet was unique in that it had no ships of its own but could order any ship of any U. S. fleet to go anywhere.

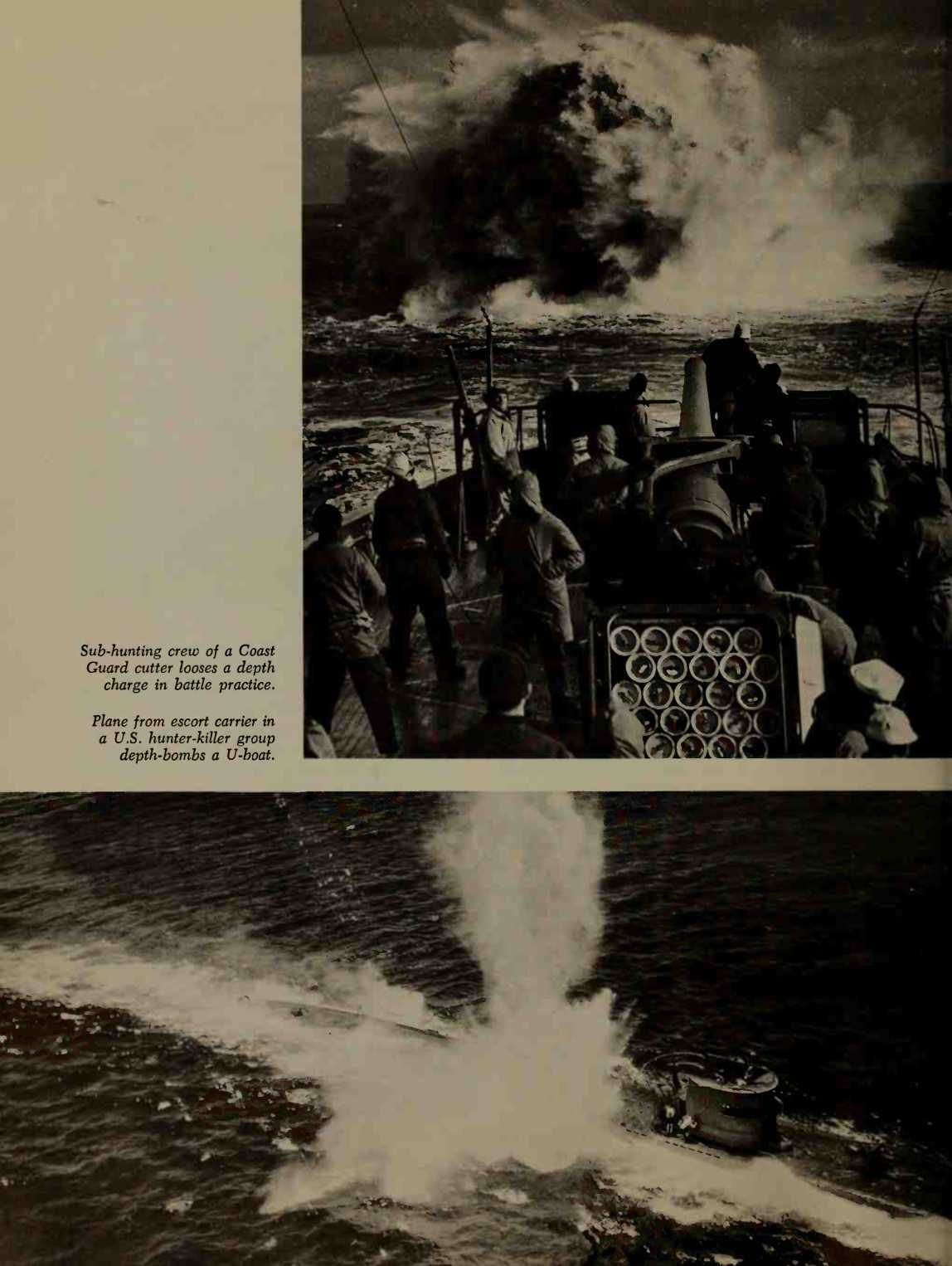

Improved antisubmarine techniques cost the Germans a record 41 U-boats in May 1943, mostly in the North Atlantic. Donitz, badly shaken, ordered most of his submarines southward into the Central Atlantic. This move was scarcely for the better, for here American hunter-killer groups were just going into operation. These groups consisted of an escort aircraft carrier (CVE) screened by old destroyers or destroyer escorts.

First of the new antisubmarine groups to operate in the Central Atlantic was that of Captain Giles E. Short, in the escort carrier Bogue. On June 5, a Wildcat and an Avenger from this carrier attacked and sank U-217. On the 8th, well-armed U-758 fought back against Bogue planes and dived to safety. Four days later, seven planes from the carrier sank the milk cow U-118. Next to arrive in the Central Atlantic were groups centered on the escort carriers Core, Santee, and Card. In less than three weeks the hunter-killers had sunk 15 U-boats with a loss of only three planes.

The operations of these groups were a far cry from the needle-in-haystack searches of World War Is Queenstown patrols. The U-boats, in order to keep in touch with Donitz as he required, were continually breaking radio silence. The U. S. Navy’s Atlantic arc of high frequency radio direction finders (HF/DF, pronounced “huffduff”) picked up German transmissions and flashed the bearings to Washington headquarters, which established a fix and radioed it out to the hunter-killer groups. The group nearest to the transmitting submarine immediately sent planes to sink it. All this took place so swiftly that the attacking aircraft often arrived over the U-boat before it could close down transmission and submerge. Donitz’s boats were thus talking themselves to death.

THE FINAL CAMPAIGNS

While improved antisubmarine techniques were decimating Donitz’s U-boats in the North and Central

WORLD WAR II

I66

Atlantic, aircraft and ships based on southwest England were attacking them in the Bay of Biscay, across the surface of which the boats passed by night to and from their French bases. Air Vice Marshal Sir John Slessor called the bay “the trunk of the Atlantic U-boat menace, the roots being in the Biscay ports and the branches spreading far and wide. ” Planes of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command had been patrolling this “trunk” since 1940. They had, however, sunk no U-boats for lack of long-range bombers, none of which could be spared from the strategic bombing of Cermany.

In early 1943 the U. S. Army loaned the Coastal Command 36 radar-equipped B-24 bombers, but because these bombers succeeded in sinking only one submarine in a month’s time, the Joint Chiefs transferred them to Morocco to support the North African campaign. The

B-24S had been foiled by Metox, a Cerman radar detector that outranged the planes’ radar and hence gave early warning.

Coastal Command next obtained a few Wellington bombers equipped with 8o-million-candlepower searchlights and new ultrahigh frequency radar which Metox could not detect. The Wellingtons were thus able to surprise and blind the night-running U-boats, which however usually managed to crash-dive and escape. In April, 27 bomber attacks achieved only one kill.

Donitz nevertheless made the fatal mistake of arming his submarines with powerful antiaircraft guns and ordering them to surface by day to recharge batteries and to fight back if surprised. As a result the Wellingtons, aided by a few newly arrived Halifax heavy bombers and Simderland flying boats, in May sank

Boarding party on U-505.

Captain Gallery on the Guadalcanal, with his prize in the background.

Seven boats and damaged seven. Admiral King, impressed by this score, sent to the bay offensive several squadrons of B-24S and one of PBY patrol bombers, and the Royal Navy added five sloops, two of which promptly sank a U-boat apiece.

The improving scores reached spectacular heights in the "Big Bay Slaughter” of the week of July 28, when nine boats were sunk in six days. Thereafter the rate of sinkings decreased as many U-boats shifted to new submarine bases in Norway; those that continued to be based on France came and went hugging the Spanish coast, where the mountain backdrop made them invisible to radar. Nevertheless, between May 1 and the end of 1943, 32 U-boats had been sunk in the Bay of Biscay and its approaches.

Out in the Central Atlantic the American hunter-killer groups, aided by huffduff and by cryptanalysis of radio messages sent to and from the garrulous U-boats, had developed a specialty of catching the submarines fueling from their milk cows. With the pipeline stretched between them, neither submarine could dive, and hence the attacking planes often got both. Loss of milk cows obliged Donitz in September 1943 to cease active operations in the Central Atlantic. But U-boats en route to assignments off Capetown or in the Indian Ocean had to pass through the area and refuel near the Azores or the Cape Verdes. In March 1944 the Block Island group sank two U-boats at each of these fueling stops; one sub was a milk cow.

A striking example of the coordination between huff-duff and the killer groups was the hounding of U-66, which was en route from South Africa and was short of fuel. On April 19 the submarine’s captain. Lieutenant

Seehausen, radioed a request, monitored by huffduff, for instructions on where to rendezvous with a milk cow. In the predawn darkness of the 26th, as Seehausen approached the appointed spot, he was horrified to see four American destroyer escorts already there, attacking the milk cow U-488, which they destroyed. Seehausen dived and slipped away, but after he had requested another rendezvous, huffduff and the hunter-killers were soon again on his track. On May 5 the badly frustrated U-boat captain despairingly radioed Berlin: “Refueling impossible under constant stalking. Mid-Atlantic worse than Bay of Biscay.” This message, spurt-transmitted— that is, recorded on tape and radioed at high speed —was on the air only a few seconds, but 26 huffduff stations took bearings on it. Within an hour the Block Island had the fix and sent the destroyer escort Buckley to run down the bearing. The Buckley found U-66, opened fire, dodged a torpedo, and then rammed the U-boat, which began to blaze, whereupon desperate Germans tried to clamber aboard the Buckley. The Americans, taking them to be a boarding party, beat them off with anything handy, including coffee cups and shell cases. After U-66 had gone down hissing, the Buckley rescued 36 survivors.

Even more spectacular was the June 1944 capture of U-505 by Captain Daniel V. Gallery’s group built around the escort carrier Guadalcanal. The Germans, blasted to the surface by depth charges and ahead-thrown projectiles called hedgehogs, hastily abandoned U-505, whereupon a specially trained American boarding party plunged down the conning tower hatch, disconnected demolition charges, and closed seacocks. They brought out code books and a cipher machine, for which Ameri-

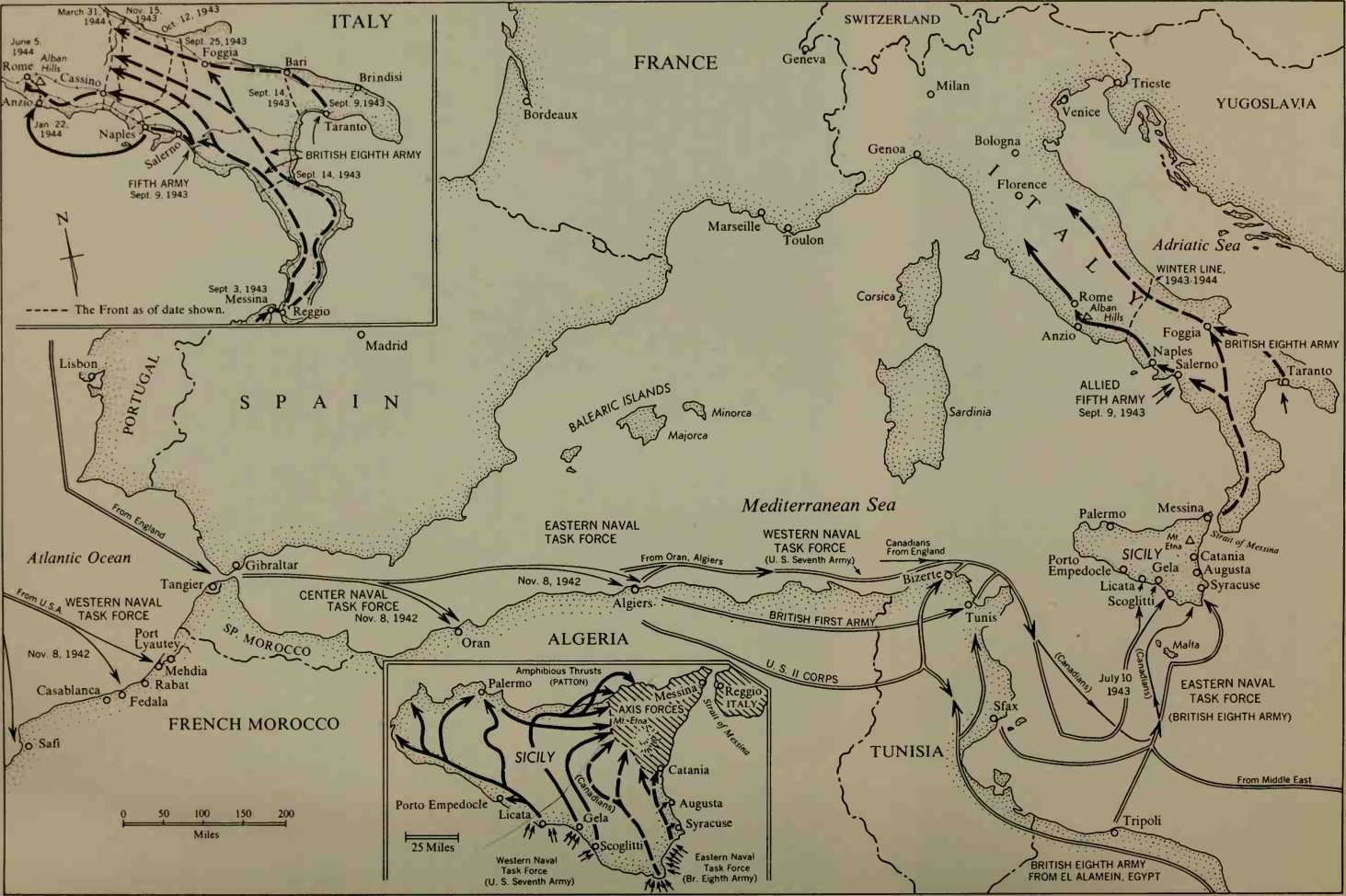

Allied campaigns in the Mediterranean theater, 1942-43.

Western Naval Task Force en route to Morocco-.

Can cryptanalysts were grateful, since these acquisitions greatly simplified their brain-cracking labors. Gallery, after pumping out the partly flooded U-boat, put a line on her and towed her to Bermuda.

In the last months of the war, when U-boats had become little more than a nuisance, new German snorkel boats, whose breathing tubes permitted them to remain submerged with diesels running, staged a blitz in British coastal waters. Reports from spies that seven snorkelers were about to cross the Atlantic to launch rockets at East Goast cities caused such apprehension that GIN-GLANT set up a barrier of ships to intercept them. The barrier sank five of the U-boats. The others reached the American coast after Germany’s defeat and quietly surrendered. These submarines were found to be carrying no rockets.

World History

World History