The placement of the remains of the deceased is a ‘conscious and carefully thought out activity by which the dead are both remembered and forgotten, and through which we reaffirm and construct our attitudes to death and the dead and, through these, to place and identity.’912 Mike Parker Pearson notes cases where the dead are physically separated from the living by being buried on the opposite side of the stream from a settlement, or tombs built with different alignments to the cardinal points from houses:913 ‘By examining how these juxtapositions changed through time, we may be able to examine some of the ways in which the dead were conceived of by the living and how much influence they were considered to exert’. On the basis of such an analysis, it could be argued that at Deir el-Medina in the 19th and 20th Dynasties the dead

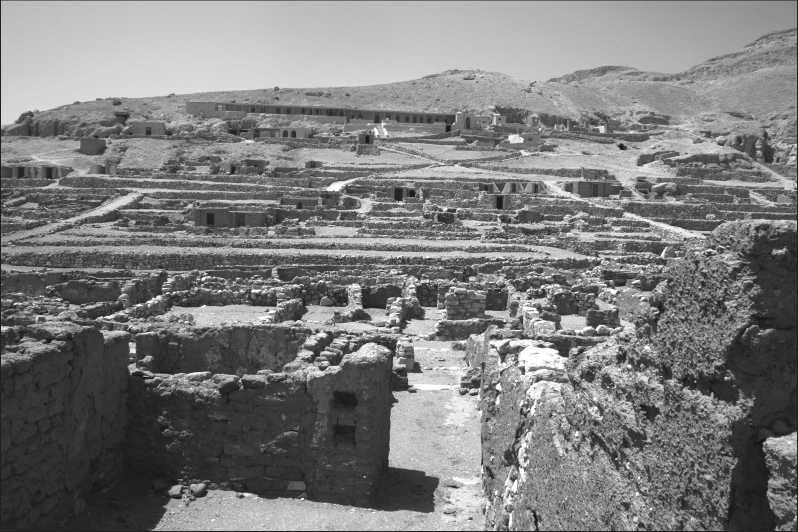

Figure 51: View of the western tombs at Deir el-Medina from one of the village houses.

Were thought to exert a significant degree of influence on the lives of the villagers. Not only was the settlement flanked by tombs to the west and earlier burial pits to the east, but the elite necropolis was visible to the north (Figures 51, 52, 53). The creation of enduring monuments aided in the demarcation of the settlement’s boundaries, establishing the identities and claims of the society within, and providing a sense of permanence and stability.914

The decision about where to place memorials in the landscape involved envisaging them as accessible cult places in years to come and is an expression of the importance of the dead to society. In this way, the landscape may be an integral part of the monuments rather than a neutral backdrop for them.915 It is possible that in planned settlements such as Deir el-Medina the occupants’ desire for stone memorials developed from a need to create fixed commemorative spaces having left any ancestral monuments and burials behind. Tombs with clearly defined superstructures916 were a link to both the communal past and the individual dead. Such a connection between tombs and the establishment of societies can be seen in ancient Jordan:917 ‘in creating enduring, visible monuments to the dead, the Early Bronze Age people literally inscribed their histories, identities, claims and rights across the very fields, hills, and river valleys in which they worked, played and lived.’

Proximity to sacred space was probably the main factor that influenced the location of the Theban necropolis and encouraged its reuse over several centuries. The pylons of Karnak temple are visible from Dra Abu el-Naga, for example,918 and many tombs were built beside or within sight of the processional route of the Beautiful Festival of the Wadi.919 The desire to be close to the gods and participate in festivals is also seen at Abydos,920 where statues and stelae were erected by processional routes, and which was a place of ‘pilgrimage’ both in life and after death.921

One of the greatest problems in discussing Egyptian burial practices is the near-absence of nonelite cemeteries. One of the most promising sites for the investigation of lower status burials in the New Kingdom is the South Tombs Cemetery at Amarna. Fourteen stelae have been discovered at the site so far, with rough cairns created from local boulders being the main means of demarcating graves.922 The excavator suggests that the unusual pointed stelae found in the cemetery recall a mountainous landscape and were intended to ‘combine a memorial representation of the deceased with a model of a rock-cut tomb, and therein a self-contained body-tomb substitute’. She also notes that, unlike round-topped stelae, pointed stelae are not found in Amarna houses because ‘their role was largely that of landscape modifiers within a funerary context.’923 Aside from the inscribed stelae, the absence of names in association with the majority of graves may reflect illiteracy, and would probably have meant that those buried in the cemetery would have been forgotten within a generation or two.924 In her analysis of Roman burial practices, Hope925 suggests that the funeral itself may have been the chief form of commemoration for some members of society, with simple grave markers erected as a focus for the bereaved.

World History

World History