The latter part of the 20th century saw many archaeologists dismiss the significance of swords as archaeological indicators. This treatment of swords was part of a wider trend that rejected militaristic explanations of prehistory, and was especially harsh on 'invasion hypotheses'. However, it seems hardly sensible to ignore or dismiss artefacts that have maintained a continuous existence as prestige symbols among European elites for the last 4000 years.

That said, care must be taken not to place undue emphasis on swords, or assign qualities to them that are the result of more recent imagination. Despite the best attempts of fiction-writers to convince the public otherwise, there is no evidence for swords being imbued with mystical significance in Iron-Age Eurof>e. Named swords, such as Excalibur, are rcx)ted in medieval romance, and swords appear to have been buried with their owners or deposited in rivers or lakes, rather than handed down from generation to generation.

What is perhaps most repellent about a fascination with swords, is that a sword is fundamentally the most efficient and convenient method of slaughtering human beings by hand. Although swords were used by societies as prestige items, badges of rank, or symbols of authority, they were rooted in this bloody reality.

Birth of the sword The sword first appeared in the Bronze Age. Older materials such as stone and copper were not strong enough to make a practical sword, although the idea is prefigured in the 30-centimetre (12-inch) flint blade found in a 6000-year-old cemetery at Varna, eastern Bulgaria.

Swords developed out of short, bronze daggers that were initially made with a separate blade attached to a handgrip with rivets. The same blades could also be attached at right angles to a longer handle to make a halberd (a fighting pick). Early swords were made in the same way, the extended blades could be strengthened with folds and ribs but the weakness of the riveted attachment to the handgrip was a serious limitation upon the fighting qualities of the weapons. Subsequent innovations produced tanged blades, where the grips are fitted onto a continuous length of metal. Organic materials, such as antler and horn, seem to have been favoured as handles for fighting swords, while those intended primarily for display had elaborate metal hilts. However, functionality was never entirely sacrificed to demands of decoration, and no purely ornamental swords have been found.

Sword fighting

Against poorly armed opponents, such as recalcitrant farmers, the sword is a simple tool of butchery. Against equally matched opposition, such as fellow members of the elite, it was a weapon admirably suited to contests of a more 'sporting' nature. The type of sword dictated both the style of this sport and its accompanying ritual code.

For the early smiths, making a sword was a compromise between length, which increased the user's reach, strength, which dictated how the weapon would behave in battle, and weight, which affected the ability of the user to wield the sword. Early long swords, such as those used by the Mycenaeans, were fairly weak and narrow. Such swords dictated a certain style of fighting because their lethality lay in the point, and they were unsuited to a swinging, slashing style of fighting. Later European swords were wider and stronger, with two sharp edges to supplement the point. The subsequent history of swordfighting, either in war or sport, has essentially been one of changing fashions in the emphasis placed on either the edges or the point.

Swords were by no means the only weapons used by European warriors, and they never dominated the battlefields. Spears were used in much greater numbers, while axes, particularly in the east of the Hallstatt area, retained their traditional status, and were often carried in preference to swords. Neither the spear nor the axe, however, offered the user such a wealth of opportunities for demonstrating both individual skill and personal courage - two of the most highly esteemed qualities among groups of warrior-elites.

It is generally accepted that the adoption of longer swords by central European peoples near the start of the Iron Age is linked to the introduction of cavalry onto the battlefield, because a mounted warrior can wield a longer sword to greater effect than his comrades (or enemies) fighting on foot. However, the link between long swords and cavalry is by no means proven, and during the

Subsequent Hallstatt D period, swords became shorter, only to become longer again in the La Tene period, with blades reaching 90 centimetres (36 inches) in length. These changing styles, and the elaborate decoration of the sword hilts, reflect the individuality and prestige of their owners, whether mounted or not.

The Romans, methodical in all things, eventually settled on the very antithesis of the long La Tene sword - the short, broad-bladed gladius. The gladius was perfectly suited to the closely drilled tactics of the Roman legions, who advanced en masse, shield to shield, hacking and stabbing with their swords. The swords carried by their Celtic foes suggest more expansive and individualistic behaviour.

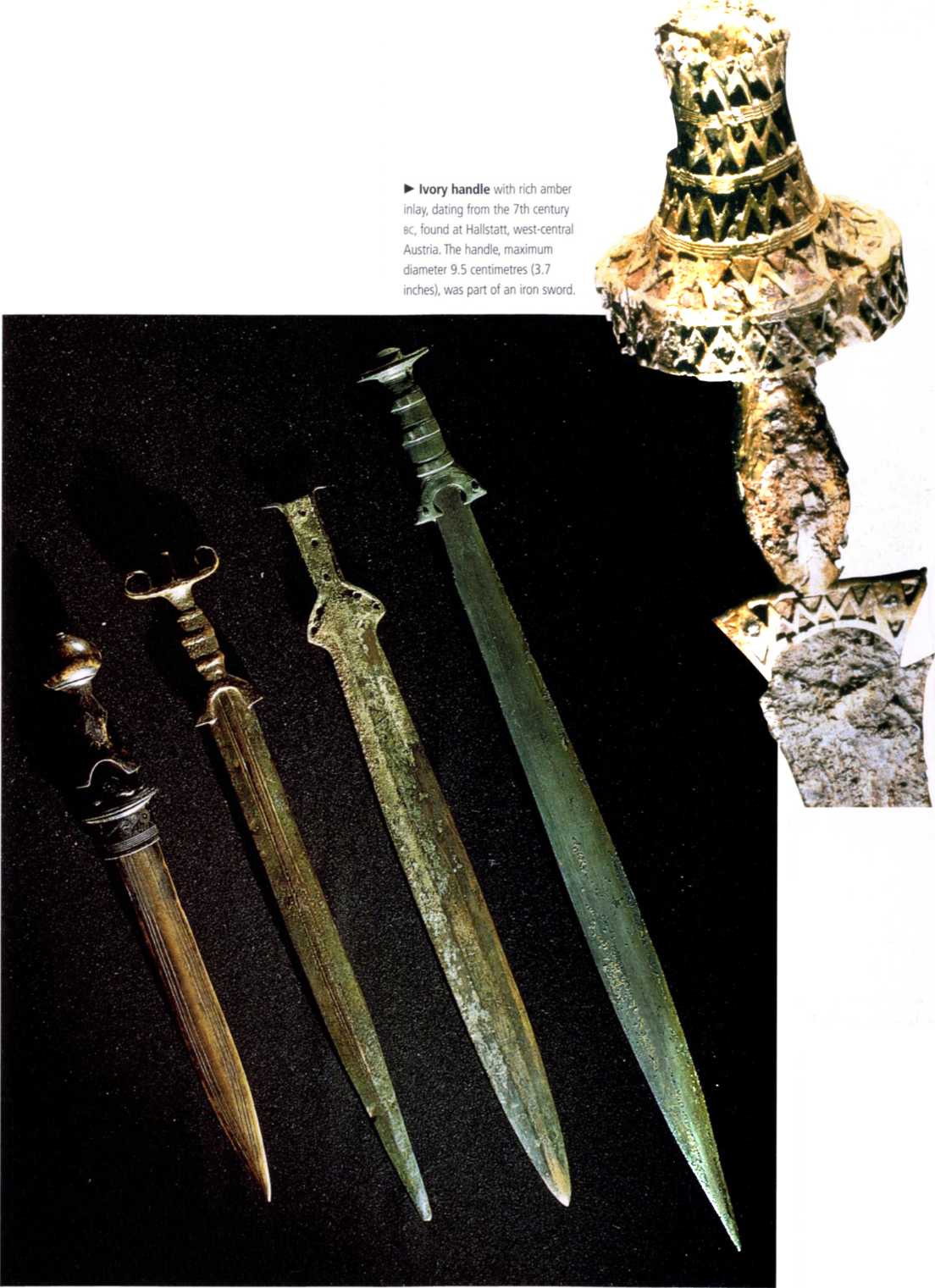

< These four swords are a

Good example of the variety of swords produced in the Late Bronze Age (1250-850 bc). Working from right to left, the longest weapon is a Liptau-type sword; next is the tongue-shaped sword; then the so-called antenna-type sword; finally, the shortest sword is almost dagger length. All four are made entirely of bronze.

World History

World History