The administrative apparatus of the Komnenoi survived in an evolved form under the rulers of Nicaea, and formed the basis of the last two centuries of Byzantine imperial administration, although there were important differences between the European and the Anatolian areas. In Asia Minor, and as with the arrangements of the twelfth century, the theme was the chief unit of provincial administration, commanded by its doux. The themes were themselves groups of smaller geographical units based around key fortresses and towns and called katepanikia, in turn divided into smaller units referred to by the terms chora or enorion, ‘district’, generally made up of several villages and their lands. At its greatest extent in the years just before the recovery of Constantinople from the Latins in 1261, there were some seven themata. From the north-east in an anticlockwise direction these were: Paphlagonia, Optimaton opposite Constantinople, Bithynia and then Opsikion (although it was probably referred to as Troados or Skamandros under the Nicene emperors), Neokastra, Thrakesion and Mylasa and Melanoudion. In addition to these provinces there were also a number of frontier districts such as the themata of Philadelphia and that of the Maeander, both technically under the authority of the doux of Thrakesion, but having a certain independence in military affairs and placed under their own governors, with the title of stratopedarches. No doubt the boundaries of these themes were different in many respects from those of their like-named predecessors in the twelfth century - it is clear, for example, that the theme of Thrakesion was enlarged at the expense of that of Mylasa and Melanoudion to the south - but the emperors at Nicaea attempted to preserve or reestablish the earlier arrangements. In the Aegean, the system seems less clear, since most islands had their own governors, although for fiscal purposes they were grouped into larger circumscriptions. The presence of so many independent military and civil commanders may reflect the needs of local defence against both pirates and more dangerous enemies. In the European regions of the empire, the themes of Strymon and Thessalonica reflected the earlier arrangements, as did that of Boleron, although all three had been part of a single unit before the Fourth Crusade. The frontier districts were generally very small, consisting of a single fortress or city with its immediate hinterland, and the governors were effectively military commanders, usually called ‘heads’ (kephalai) after 1261. Before this date such officers seem to have a had a good deal of autonomy and were effective senior officials. After the recovery of Constantinople they shared power with officials appointed directly by the emperor, such as the prokathemenoi in the larger cities and the local kastrophylakes in charge of fortresses.

The governors or ‘dukes’ - doukes - of the provinces were all members of the imperial household under the Nicene

Emperors, although after the recovery of Constantinople this was not always the case. The majority were members of the upper or middling aristocracy also. The most important officer below each duke was the stratopedarch or military commander (a post sometimes held together with the position of duke), probably responsible both for military and tactical administration as well as for liaising with the financial departments in respect of military supplies and recruitment. In addition to the stratopedarch there were also commanders of fortresses and towns. The centre of the administrative apparatus was the duke’s own household and headquarters. He had secretarial staff headed by a grammatikos, a financial manager or logariastes, in charge of fiscal affairs. He was himself responsible for supervising the administration ofjustice and the maintenance within his jurisdiction of law and order, which was achieved through the stratopedarch. Technically the duke was also commander-in-chief within his theme, but in practice the imperial field army under the Grand Domestic (megas domestikos) absorbed most of his soldiers apart from the militia garrisons of the forts and frontier cities, and he may have had little more than an administrative role, including supervising the holders of pronoiai (revenue grants in land to support military service).

Within each theme, the katepanikion was managed by an appointee of the doux, called a praktor or energon, who was responsible for fiscal affairs in his district as well as basic administration and the local level of justice. The district officers also liaised closely with the village communities in their areas, each represented by a group of senior (wealthier, more important) villagers (including the village headman and the local priest), both in respect of fiscal as well as judicial affairs. Parallel with the katepanikia were the major cities of the theme, which had their own separate administration. Here the governor, generally referred to by the title prokathemenos, was appointed directly by the emperor, a reflection in part of the strategic and economic as well as political importance of such centres as Smyrna, Ephesos, Philadelphia and, of course, Nikaia itself. Such governorships, which incorporated judicial as well as administrative duties, were probably also a development of the Komnenian period. In many cases, especially where a military role was important, the governor would be assisted by an officer entitled kastrophylax, in charge of the garrison and the defence of the city or fortress.

While this organisational structure represented an effective way of managing resources and strategy, the larger cities always retained a degree of autonomy, a reflection of the presence of the wealthier local landowners in the affairs of the urban community, of the presence of some of their number among the higher levels of the imperial and provincial administration, and of the role of the church and the local bishop in such affairs. The role of the local elites was more pronounced in the European provinces, where a stronger tradition of political independence had developed in the context of the wars of the later twelfth century and the conflict over Thrace and Macedonia between Epiros, the Latins, Nicaea and other interests in the region - Latins and Bulgars, for example; although the elite of Trebizond provides an important exception.

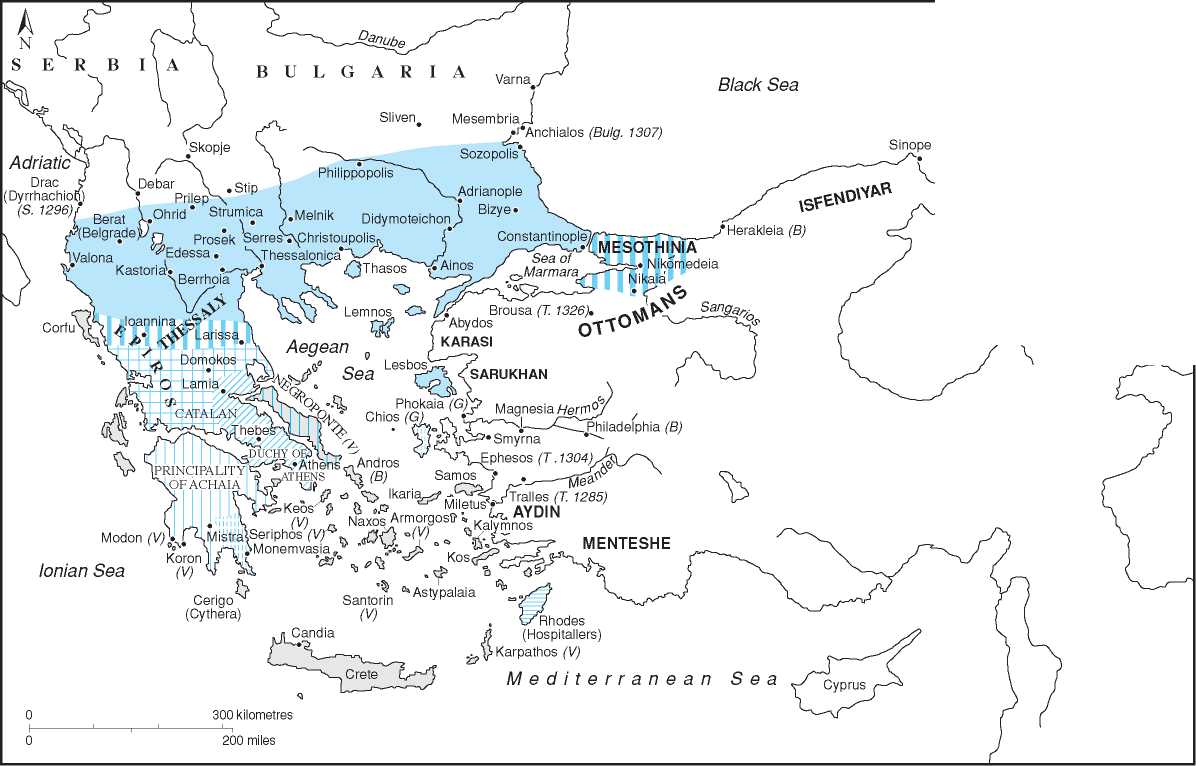

Map 10.2 Provincial administration 1204-1453 (the empire c. 1330).

World History

World History