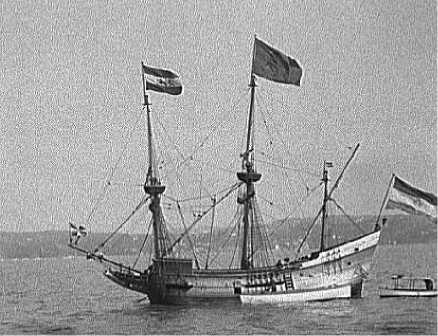

The mercantile system was controlled through a series of Navigation Acts. The thrust of those Acts was to keep profitable trade under British control in order to bring as much wealth as possible into English pockets. In general the Acts said that insofar as possible, goods shipped to and from English ports must be carried in English ships. Within the Empire (i. e., between the colonies and mother country), foreign vessels were generally excluded. These Navigation Laws were not pointed at the colonists but rather at the Dutch and others who "took" trade away from the British.

Note: The colonists had no objection to the Navigation Acts in theory, as they were not directed against colonies, but against Britain's competitors. They were seen not so much as taxation as regulation. (The issue of "taxation without representation" was not yet in focus.) Nevertheless, the colonists still found the navigation laws an irritant because in practice they tended to work for the interest of the mother country at the expense of the colonies.

So Americans avoided paying duties whenever they could get away with it, which in fact was most of the time. It was too expensive for the British to try to collect duties in lightly populated America, a condition of which the colonists happily took advantage.

The Navigation Acts also demanded that most raw materials be imported into England from the colonies in order to support British manufacturing. Conversely, the colonies were often prohibited from exporting manufactured goods to the mother country because they would compete with British manufactures. For a time, Virginia tobacco could be sold only in England, even though the Dutch might pay more for it. On the other hand, the growing of tobacco in England was prohibited.

The first major Navigation Acts of 1650 and 1651 forbade the importation into England of all goods except those carried by English ships or ships owned by the producing country, eliminating third-party carriers. Foreign ships were barred from trading in the colonies. It should be noted in all these acts that the colonies were part of the Empire, and thus colonial ships were British ships. Also, as stated above, these acts were not aimed against the colonies, but rather against the Dutch traders, who challenged British domination of the seas. Eventually these Acts led to war between the British and Dutch.

The second major Navigation Act was passed in 1660, and it forbade the importing into or the exporting from the British colonies of any goods except in English or colonial ships (with one-fourth of the crew British) and it forbade certain colonial articles such as sugar, tobacco, wool, and cotton from being shipped to any country except to England or some English plantation in order to keep them from competitors.

Additional Acts passed in the 1660s and 1670s sought further control of the kinds of goods that could be shipped to and from the colonies and the methods by which they could be shipped. Some of the Acts were also designed to tighten enforcement, as patrolling the lengthy coastline of America with its many bays and rivers was extremely difficult and costly. The net result was that the Navigation Acts, although rigorous on paper, were very loosely enforced, and the colonists became habitual offenders and smugglers.

In 1675 King Charles II designated certain Privy Councilors as "Lords of Trade and Plantations" in order to make colonial trade more profitable. From then until 1696, the Lords of Trade handled most colonial matters, though it must be said that colonial affairs ranked low on the King's list of priorities. The 1696 Navigation Act confined all colonial trade to English-built ships and tried once again to toughen enforcement procedures in order to collect duties. In addition it voided all colonial laws passed in opposition to the Navigation Acts and created the Board of Commissioners for Trade and Plantations. The Board's fifteen members were supposed to provide centralized control of colonial affairs.

Some Navigation Acts (mercantile laws) and their application:

|

1621 |

Virginia tobacco can be sold only in England. English tobacco crop prohibited. |

|

1650-51 |

Navigation Acts forbid import of goods except in English ships or in ships owned by producing country (no third parties.) Foreign ships were barred from the colonies. These acts and not anti-colonial, but aimed at the Dutch. The Anglo-Dutch Wars break out 1652; peace is reestablished in 1654. |

|

1660 |

Provides for no goods in and out of colonies except in British ships or ships with one-fourth British crews; certain goods (indigo, sugar, tobacco) may be shipped only to England. |

|

1662 |

Goods may be imported in English-built ships only |

|

1663 |

Staples Act: European goods bound for the colonies must go in English-built ships from England. Colonial governors may grant authority to naval officers. |

|

1673 |

Duties are to be assessed at port of clearance to prevent plantation owners from evading laws; also, inter-colonial duties imposed on tobacco, sugar, and so on. |

|

1675 |

Charles II designates certain Privy Councilors as "Lords of Trade and Plantations"; seeks to make colonies more profitable; Lords of Trade handle virtually all colonial affairs. |

|

1696 |

Act confines all colonial trade to English-built ships; toughens enforcement procedures to collect duties; voids colonial laws passed in opposition to the Navigation Acts; creates the Board of Commissioners for Trade and Plantations. The Board's fifteen members provide centralized control. |

|

1698 |

Wool Act—prohibits export of colonial woolen cloth—raw wool only. |

|

1732 |

Hat Act—no hats exported from colonies. Danbury, Connecticut, hit. |

|

1733 |

Molasses Act—protects West Indian planters; imposes high duty on rum; virtually unenforceable in the colonies because of smuggling—Americans very adept. |

|

1750 |

Iron Act—bans iron finishing in colonies; ensures sufficient pig-iron supply to England. |

|

1764 |

Sugar Act—The beginning of the pre-Revolutionary acts. See next section. |

Additional navigation and Trade Acts in the 1700s raised further restrictions, and although not so intended, the Acts nevertheless alienated the colonists, who often suffered from them—in theory, if not in practice, because of lax enforcement. Colonial governors could enforce these acts only with difficulty, and even though various levels of authority were granted to naval officers, enforcement was expensive and, in the end, impractical. Although the seeds of revolution do not begin to take hold firmly until the 1760s, tension grew between the colonies and mother country throughout the early 1700s.

The English considered that their mercantile policies would benefit the Empire and necessarily all its many parts—(a rising tide lifts all boats)—and leaders were willing to sacrifice local interests for the broader market. This policy was not unreasonable in the main, and the colonists generally prospered under British mercantilism, though they sometimes failed to understand that restrictions were aimed at others, not at them. Bottom line: When acts were passed that aided the mother country at the expense of the colonies, the colonists tended to take it personally. On the other hand, mercantilism was practically impossible to enforce, especially in the thinly populated colonies. The volume of trade was so small that aggressive enforcement of duties, for example, would not pay. Smuggling became a "respectable" profession in the colonies and paid off.

Summary of Mercantilism: Economic Imperialism vs. Free Enterprise: Mother Country vs. Colony. What's good for the Empire is good for all its parts—a rising tide lifts all boats.

World History

World History