The Interstate Highway Act of 1956, known officially as the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, created more than

40,000 miles of expressways, providing a comprehensive system of roads that mobilized Americans in an increasingly fast-paced society.

By the beginning of the 1950s, congested traffic plagued urban areas, while roads in poor repair cost drivers time, money, and occasionally their lives. Support for an interstate highway system, which would connect America’s major cities to facilitate commerce and travel, had been growing since the early 20th century. Until the end of World War II, however, America’s railroads constituted the primary method of transporting goods and people. In 1944, Congress authorized a national system of interstate highways, although no source of funding was designated for this purpose. Plans for an interstate system stalled again during the KOREAN War, which diverted supplies from the construction industry.

When Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, America’s highways were in dire shape. The post-World War II economic boom jumpstarted car sales, and, whereas America’s traffic volume in 1950 had already surpassed levels predicted for 1958, Americans were still driving on roads built mostly before 1930. Eisenhower felt that construction of an interstate system would create numerous jobs and make travel more efficient and pleasant. The threat of nuclear warfare, always present during the COLD war, made the efficient evacuation of American cities a priority as well. In the event of nuclear attack, the existing roads of most American cities would be hopelessly clogged with traffic. A president anxious to cure America’s highway ills, combined with an added defensive impetus, lent increased weight to the great wave of popular and political support for a revamped highway system.

Although most Americans agreed on the need for a new highway system, no one could agree on its primary pur-

Inventions 159

Pose or on how to fund its construction. Engineers sought to alleviate traffic problems while city officials wanted to build the highway system as a way of revitalizing decaying downtown areas. Few auto users, truckers especially, were willing to pay extra taxes to fund construction, especially because auto taxes had been diverted in the past from highway funding to nonrelated areas.

In 1954, Eisenhower appointed Lucius Clay to head the President’s Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program in order to formulate a working proposal to build and fund the interstate highway system. According to Clay’s plan, the federal government would pay as much as 90 percent of the costs of building the highways using bonds and taxes, while the states would pay the remainder. Like all previous highway bills, Clay’s proposal fell victim to a gridlocked Congress, while politicians and the so-called

Highway lobby—a fragmented group of transportation, construction, and motorist associations—argued over the method of funding. When Congress adjourned in August 1955 without passing a highway bill, it seemed there might never be a national highway system.

By 1956, many states were preparing to build their own highways using their own means. In April, however, the House approved a highway bill written by Hale Boggs of Louisiana and George Fallon of Maryland. The Boggs-Fallon bill managed to provide for 90 percent federal funding without imposing high taxes on truckers. Taxes on fuel, tires, and new vehicles would pay for construction, and the Highway Trust Fund was created to ensure that those taxes were not diverted to other areas. Refusing to contest the bill on partisan grounds, and under pressure to pass significant domestic legislation, the Eisenhower administration supported the bill. On June 26, the Senate passed the bill 89-1, and on the same day, the House approved it so overwhelmingly that votes were not even counted.

On June 29, Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act, bringing the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways into being. More than 40,000 miles of roads were planned at a cost of $25 billion, making it the largest public works program in history. The new interstate highway system, when finished, would connect most cities of 50,000 residents or more and all continental states with controlled-access, multilane expressways.

The Interstate Highway Act had a far-reaching impact on most Americans and much of America itself. In the end, those concerned with traffic patterns and commerce won out over those hoping to revitalize America’s inner cities. The act proved a mighty boost to the automobile, trucking, and construction industries. It cemented Americans’ well-known love affair with their cars, as the number of registered cars rose above 73 million by 1960, compared to just under 40 million in 1950. The new interstate system opened countless markets for motel and fast food restaurant chains. Yet not everyone was to thrive in the new age of highways. While 28,800 miles of highway opened between 1956 and 1969, the same period of time saw the closing of 59,400 miles of railroads to passenger service. Air quality in urban areas suffered, mass transportation fell into disuse, and expressways encouraged suburban growth, furthering the plight of inner cities.

Further reading: Mark Reutter, “The Lost Promise of the American Railroad,” Wilson Quarterly (Winter 1994): 10-35; Mark H. Rose, Interstate: Express Highway Politics, 1941-1956 (Lawrence: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1979).

—Paul Rubinson

Inventions See technology.

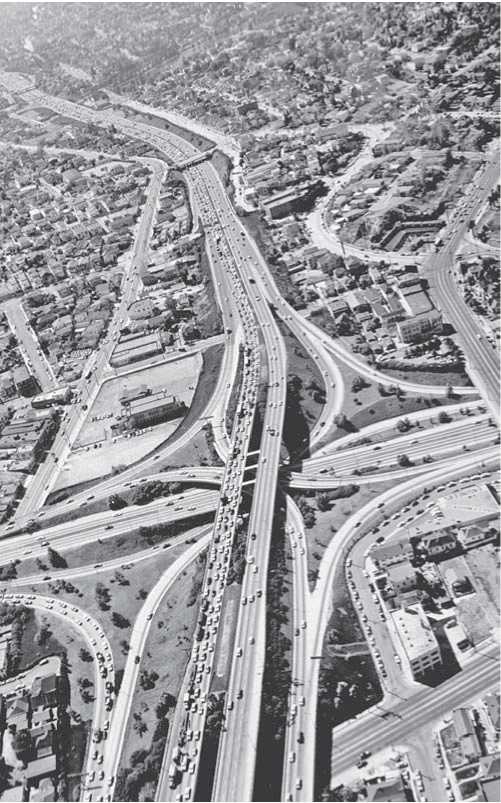

Aerial photograph of intersecting freeways in Los Angeles, 1958 (Time & Life Pictures/Cetty Images)

World History

World History