The Fulani live in various pockets across the countries of West Africa in a zone called the Sahel, an area approximately 200 to 400 kilometers wide and centered on the latitude 15°N (Figure 12.1). Largely savannah, it is too dry in most places for agriculture, but there is just enough water, grass, and salt for the cattle. Though it stretches across the entire continent, the western area has the benefit that the monsoons reach its southern edges between May and September. As to the ancient origins of the Fulani, this cannot be known with any certainty, but they seem to have spread out into this area beginning in the first millennium ce. Regardless of their origin, there can be no doubt that their mode of existence would have resembled ancient prototypes for the obvious reason that unlike the more settled Dinka and Massai, the Fulani are almost continuously moving with their cattle. Some Fulani have settled down and created farms, and are generally known as Hausa. Those that have remained true to their cattle-raising ancestry are the Wodaabe. They will break camp every two or three days, moving along streams or as the dry season intensifies from water hole to water hole. Their word gari, which refers to a watering place, means there where people sit down. Difierent groups have difierent routes, moving south in the dry season and then back north when the clouds appear. The Wodaabe have an extensive vocabulary for the types of migrations that they undertake, including longer ones that can be described as “shopping tours” to larger cities to get things that are not obtained locally. Donkeys have largely replaced the package ox in transporting people and belongings; camels are used to scout the area and for transportation purposes.

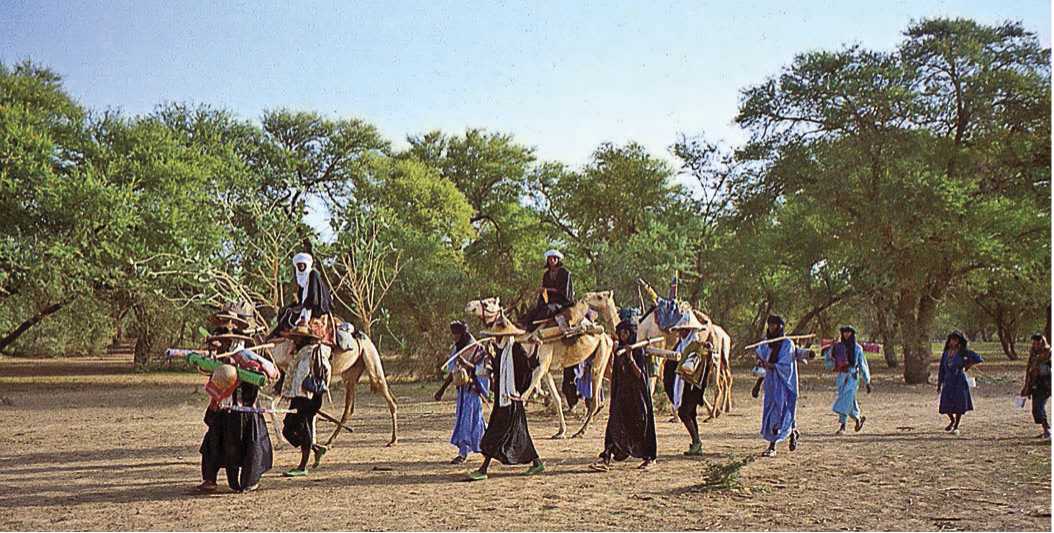

Figure 12.1: Maasai village, Serengeti, Tanzania. Source: Steve Paster

Although the agriculturalists and mobile groups of the Fulani are related, they see themselves as conceptually distinct. The Wodaabe describe the town as “smelling” and themselves as “birds of the bush.” They associate agriculture with drudgery. Nonetheless, the two groups are in close economic relationship. The Wodaabe produce milk and milk products that they exchange or sell in the markets for millet and other foods and supplies. Goats and sheep, which are a relatively recent addition to the Wodaabe economy, serve as a mobile reserve to sell at the market, in addition to sheep serving ceremonial purposes as in other Islamic communities.

The Zebu breed of cattle, which is the foundation of the Wodaabe society, is characterized by its strong attachment to its owner. It will obey and respond to his commands and will even refuse cooperation with strangers. Wodaabe also see each animal as having its own character and, in fact, use the term djikku (character) to describe both people and animals. Furthermore, each animal is not only named, but carries the same name as the animal that gave birth to it. This tradition makes it appear as if the same cow is being born again and again, thus creating long-standing continuities with the past. All in all, the Wodaabe conceptualize their relationship with their cows as a symbiotic reciprocity, where humans take care of their cows and vice versa. Since the herd is safe and strong as long as its animals keep together and do not move too far from one another, individuals are seen as safe as long as they stay close to the settlement. In the dry season, when the camps are far apart, people are, therefore, seen as more vulnerable. Hyenas are on the prowl and snakes lurk in the shadows. Equally dangerous are sinister, shape-shifting spirits, known as ginnol, who inhabit the bush and can take the appearance of both humans and animals. They usually attack only single individuals and are thus considered especially dangerous to someone traveling alone. To compensate, the Wodaabe have a strong requirement of mutual assistance. As the wet season approaches, there is a noticeable improvement in temperament as people begin to look forward to the reunification of the various clans.

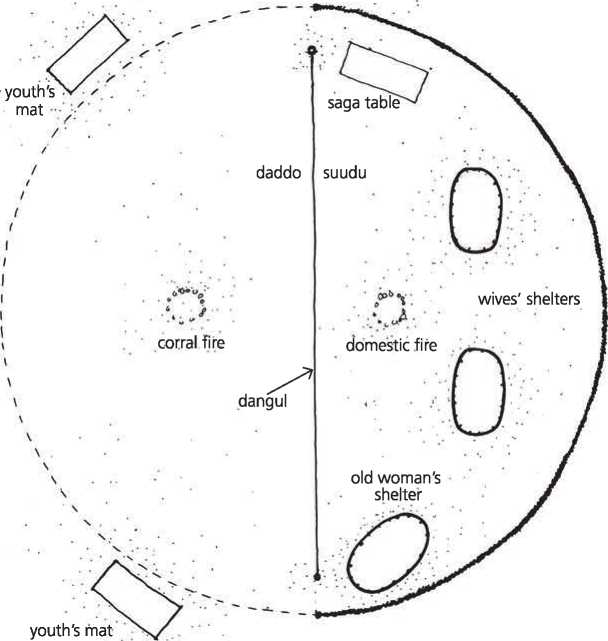

The homestead is called wuro (pl. gure), and takes the name of the male head, such as wuro Adamu, or Adamu’s homestead. It is an integrated space of human and animal settlement. Though there are no physical barriers and the view through the camp is completely unobstructed, there is a clear and important division between male and female spheres of action. The female area (suudu) is to the east, the male area, daddo, to the west, with a leather rope (dangul) running north-south separating the two domains. The rope is used to tie up the calves at night. The rope has several taboos, one of its most important being that it should not be stepped on or over. The western side is considered the front, and all access to the camp has to come from that direction.

The eastern perimeter of the suudu is defined by a curved back-fence of branches cut from nearby trees and bushes. It ensures a measure of privacy, keeps out the hyena, and deflects stampeding cattle should they be frightened. Immediately in front of the fence are the sleeping huts called suudu cekke, which literally means “house of grass mats.” The mats are made of the bark of the giant baobab tree, which is pounded into string and used to tie long strips of wild grass reed together. Red and black cotton string is interwoven with the grass in V-shaped and criss-cross patterns. It can take up to two months to produce a mat. Today, synthetic material from rice bags is also sometimes used as a more durable and less work-intensive substitute for the traditional baobab string. The mats are used only in the dry season, because rain turns them black. During the May-September rainy season, the mats are put away and the houses are covered with straw taken from surrounding fields. The huts are principally sleeping and resting areas, with the women working together outdoors near the hearths (Figure 12.2).

The centerpiece of the hut is the bed. These are made of four forked stakes driven into the ground at the corners and two stout poles. Smaller sticks make the bed and mats serve as bedding. In recent centuries, the Wodaabe, as they moved northward from the Sokoto region, adopted the bed styles of the Tuareq, who are nomadic camel herders from the north. These beds are quite elaborate and, as the most important possession of each family, a gift from the bride’s mother. They become the wife’s property and are burnt at her death. The bed comes as a kit of parts consisting of the sticks for the bed and four drum-shaped feet. This protects the user from snakes and from the cold, sandy floor. The bed is not made by the Wodaabe, but by settlement-based Hausa woodcarvers and leatherworkers. All the objects of the house belong to the woman, and she is responsible for packing them and the house and rebuilding it after each movement. Since the bed is owned by the wife, if a man has no wife, he has no house.

Figure 12.2: Woodabee leaving camp, Niger. Source: Dan Lundberg

Figure 12.3: Wodaabe camp, Niger plan diagram. Source: Timothy Cooke/Derrick J. Stenning, Savannah Nomads: A Study of Wodaabe Pastoral Fulani of Western Bornu Province Northern Region, Nigeria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 106, 230

The senior wife’s bed is on the north side, with the rest of the huts in descending order of rank lined to the south (Figure 12.3). The senior wife is described as “the north one.” The only males who sleep in this part of the homestead are the household head and his infant sons. The head man has no bed of his own, but sleeps in the beds of his wives in rotation. The wife with whom he sleeps cooks an evening meal for him. No males other than infant boys eat in this part of the homestead. While Wodaabe women spend their leisure time with their children and perhaps female visitors in the suudu area—usually sitting under the improvised shade of a cloth spread out—men spend their time west of the camp under the shade of a tree or a shrub. It is the woman’s role to take care of all household tasks, such as collecting water, cooking, collecting wood (if there are no children old enough to search for it), caring for small children, and weaving. Wives have rights to the milk and do most of the milking.

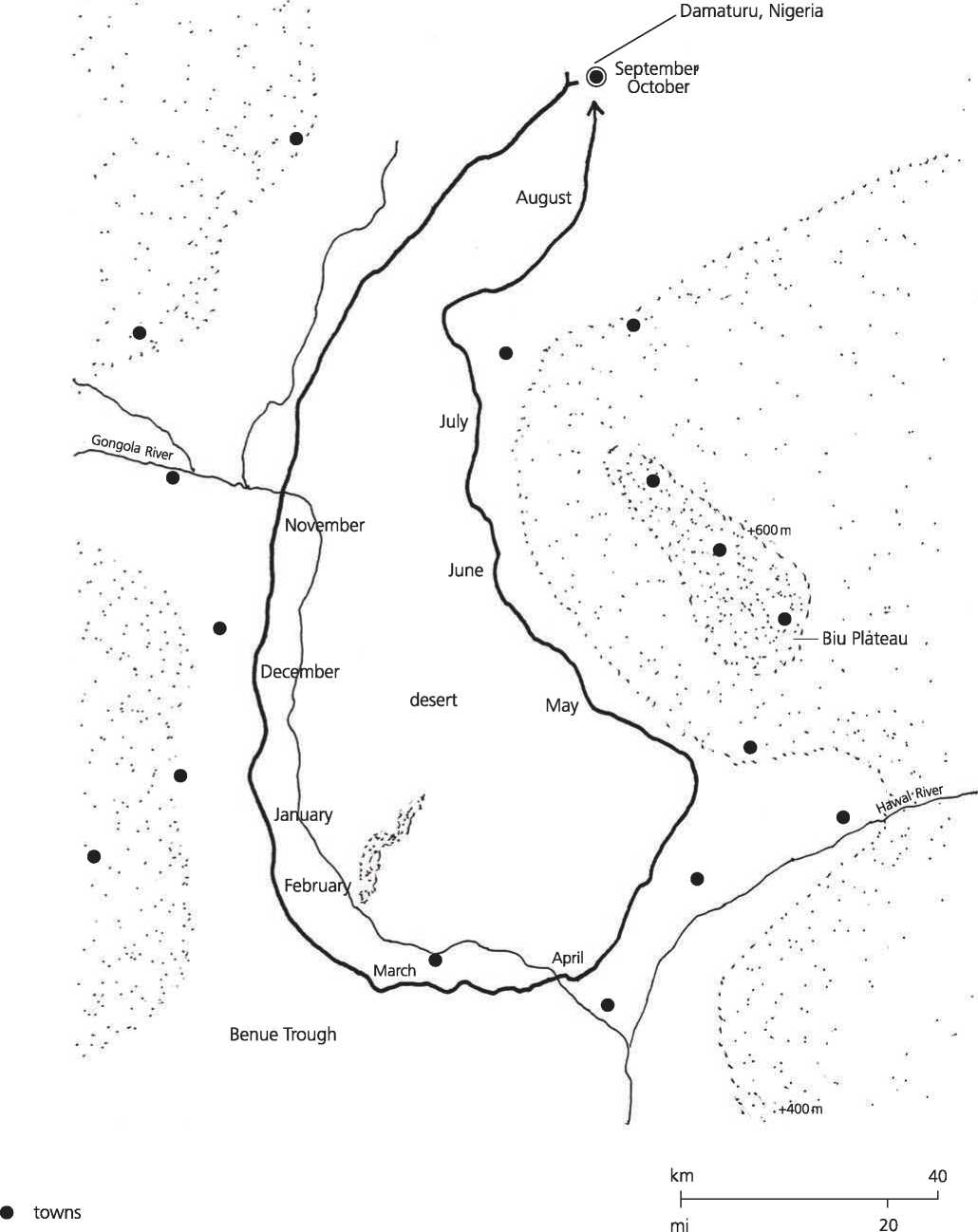

Figure 12.4: Wodaabe migration route. Source: Timothy Cooke/Derrick J. Stenning, Savannah Nomads: A Study of Wodaabe Pastoral Fulani of Western Bornu Province Northern Region, Nigeria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 230

Apart from the portable bed, the Wodaabe household consists of an improvised shelf, saga (table), placed to the north of the huts on which baskets and milk jugs are arranged and exhibited. The shelf also holds various prestige items, many of which have the attribute of being shiny. These can include drums of discarded washing machines, pieces of chrome, as well as hubcaps, bicycle lamps, and parts from old irons. Shine and glow are also one of the most valuable qualities in the cattle owned by the Wodaabe. The brown fur of the animals is thought to be particularly gleaming. The quality of shine is even something that the Wo-daabe endeavor to achieve in their personal appearance as well.

The male sphere is known as daddo. Daddo is also the name given to the inter-lineage meetings that take place during the rainy season. The word thus denotes the idea of a primarily male public and is the opposite of suudu, the private realm associated with women and female activities. At the center of this part of the camp there is a fire, into which aromatic wood is sometimes placed as a method of maintaining or increasing the herd by magical means. The fire is significant since Wodaabe origin myths state that cows were lured to join humans with the element of fire. The fire each night replicates this myth that binds humans and animals together. Furthermore, the evil ginnol will not enter the cattle corral when a fire is burning. Youths will sleep around the corral under convenient bushes or trees. Men tend to spend time repairing their homes, digging or redigging wells. They also weave a variety of items, especially rope, using grasses or the leaves of indigenous plants.

With marriage, the husband is said to “know his cattle” and is, in effect, a herd-owner. The couple will first live in the compound of the father-in-law. After the woman gives birth she is formally elevated to the status of wife and mother and acquires the right to milk her husband’s herd. The husband’s family has the obligation of providing the couple with the elements of home building. The husband’s brothers clear a space and erect the fence. The husband’s father makes a calf rope and its stakes and this is set in front of the homestead by the husband’s mother. Other family members make the mats. Meanwhile the wife’s relatives assemble clothing and cooking utensils as gifts, which are packed and travel with the wife to the husband’s father’s homestead.

Although technically nomads, they have strong clan attachments to specific territories and do not move about in an arbitrary way (Figure 12.4). Territorial rights are important as well as clan affiliations. In the dry season from October to May, groups gather near wells that had been dug, and, once these are dry, they move south along rivers to find watering holes for the animals. In June, when the wet season begins, the groups begin to move northward. In addition, movements are made to bring camps into proximity for feasts and to receive the visit of chiefs to whom they owe allegiances. At the end of the rainy season in September, the clans, as well as the Tuareg camel herders to the north, gather in several locations at the salt flats and pools near Ingall to refresh their cattle and goat herds. Here the young Wodaabe men, with elaborate makeup, feathers, and other adornments, perform dances and songs to impress marriageable women at a seven-day charm competition, known as Yaake. The male beauty ideal of the Wodaabe stresses tallness and white eyes and teeth; the men will often roll their eyes and show their teeth to emphasize these characteristics. Men will devote many hours to making themselves beautiful, applying facial makeup and wearing elaborate clothes. Usually, a pale yellow powder is applied to the face, with black kohl used on the mouth to highlight the whiteness of the teeth. A line running from the forehead to the chin is drawn to elongate the man’s nose, and many shave their hairline to show off their forehead. Wodaabe women are, of course, also concerned about their appearance and decorate their ears with large rings of brass or silver. They also dot their temples, cheeks, and lips with geometric tattoos to ward off evil spirits. Despite the flirtations of the Yaake ceremony, and the emphasis on personal magnetism, a husband’s interaction with his wife is quite formal. He may not address her by name, speak to her in an intimate way, or even hold her hand. This quiet reserve, which is called semteende, extends to the first - and second-born children, whom the parents may not directly address at all.1

World History

World History