There were a number of ways in which past communities variously, both geographically and temporally, managed to deal with health problems. These can be divided into several categories, and include herbal remedies, blood letting using leeches or cupping, cautery (using heated irons on various points of the body), bathing, minor surgery such as applying herbal dressings to (or stitching) wounds, and more major surgery such as amputation, trepanation, or dental surgery. Of course, many of these procedures are invisible when trying to observe them in skeletal remains from archaeological sites, although indirect evidence such as surgical instruments may be present. It is here when other sources of evidence are particularly helpful.

Documentary and Iconographic Evidence

Study of historical periods of time are particularly useful when it comes to evidence of medicine or surgery to treat disease in the form of documentary evidence describing treatments, and illustrations of therapy. Hippocrates, the Graeco-Roman author writing in the fifth-century BC, was particularly knowledgeable about the treatment of fractures where reduction (pulling apart the bone fragments and setting them in the right position) and splinting were recommended. This treatment of course is the mainstay of fracture therapy today. There are also many illustrations of treatment ranging from Greek vases dated to 400 BC depicting the bandaging of wounds, to the stitching of a wound in a thirteenth-century European manuscript, and major and minor surgery in Medieval illustrations. Documentary evidence also describes the extensive use of herbal remedies for specific ailments and diseases throughout history. It is likely that in prehistoric periods herbal remedies would also have been utilized for illnesses. For example, Culpeper, writing his herbal book in the post-Medieval period in England, prescribed camphor, liquorice, lungwort, mallow, poppy, polypodium, violet, and red roses for the treatment of tuberculosis. However, many remedies for illnesses prescribed by various authors were much more unconventional. For example, eating dead infant’s flesh was one remedy recommended for leprosy in Late Medieval Europe which particularly reflects the stigma attached to leprosy at this time and relates to the lack of understanding of what leprosy was and how it was contracted.

Evidence from Human Remains

There is very little direct evidence for the treatment of disease and trauma from human remains from archaeological sites. One could argue that this is because many treatments are invisible in the archaeological record because most human remains are skeletons. The only direct evidence comes in the form of trepanation, or the removal of part of the skull for various reasons, and the amputation of limbs. Most fractures identified in skeletal remains are healed and therefore we would be unlikely to see evidence for splints, even though these are described in written descriptions and illustrated in artwork for specific periods. However, there are some interesting cases of treatment other than trepanation and amputation. A unique female mummy from Naples, Italy and dated to the sixteenth century, appeared to be that of a person who had suffered syphilis; her right arm had a lesion consistent with the infection which had an ivy leaf dressing applied (antiseptic) kept in place with linen bandages. Earlier examples of treatment of wounds come from England, Belgium, and Sweden where Medieval skeletons had copper plates applied to their upper arms where evidence for infection was found (and that from England was lined with ivy leaves); in York, England a Medieval male skeleton had copper plates applied to an infected knee joint. Copper, of course, has antiseptic properties.

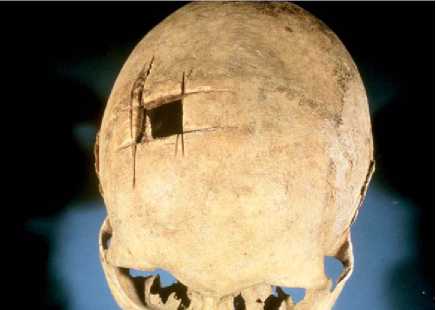

Evidence of trepanation has been found throughout the world stretching back into prehistory. Why populations practiced this surgical procedure from such a long time ago is often a mystery. Suggestions for the reason for this operation include trauma, migraine, epilepsy, and to let the spirits out. Indeed, some skulls from archaeological sites have evidence of healed head wounds and trepanation holes, indicating an obvious reason for the surgery. In Peru, research showed a frequent association of skull fracture and trepanation in skulls dated to between 400 BC and AD 1500; in Peruvian Central Highland sites, from 212 skulls with trepanation, 55.7% of males, 31.6% of females, and 26.9% of subadults had associated skull fractures (Figure 13). However, many skulls have no direct evidence to indicate why the person underwent the procedure, although intracranial infection and scurvy have been suggested for an example in Israel dated to 3500 and 2200 BC, and a meningioma for one individual from the Czech Republic dated to AD 1298-1550, respectively. A number of types of trepanation holes have been identified, including scraped (common in Britain), gouged, and sawed (common in South America), and many have evidence of healing, suggesting that the operation had been a success. In a recent study of trepanations in Britain, almost two-thirds of the 62 identified from the Neolithic to postMedieval periods had evidence of healing. What is not known is the possible associated brain damage that may have occurred during the procedure.

Amputations (Figure 14) are also evident from skeletal and mummified remains but are very rare; they may be the result of surgical treatment but could equally be due to an accident, punishment, or ritual practice. Evidence of amputation has been found in a number of places and includes a 3600-year-old hand

Figure 13 Trepanation of the skull from South America.

Figure 14 Amputation of a lower leg bone (tibia) from Late Medieval England.

Amputation in a man from Israel, the amputation of a big toe discovered in a mummy from Thebes-West, Egypt and dated to 1550-1300 BC (with replacement prosthesis), and the amputation of a lower leg and forearm in a seventh-century male from the Isles of Sicily off the southwest coast of mainland England. It is highly likely that hemorrhage, shock and death would have quickly ensued should amputation have been practiced in the past, even though there is evidence that anesthesia and control of bleeding was practiced during operations in some cultures. There is, likewise, little evidence for dental disease treatment in the past from skeletal remains although written and illustrated sources, mainly from historic periods, attest to dentistry. The few examples of clear treatment that do exist include a drilled carious tooth from the Middle Neolithic period of Denmark (3200-1800 BC), gold fillings from Illinois, United States (AD 600), a bone rosary bead used as a filling in fifteenth-century Denmark, people with gold foil fillings and porcelain, ivory and bone dentures from eighteenth/nineteenth-century Christchurch, Spital-fields, London, gold bridgework and false teeth dated to 600 BC in Italy, and a drilled tooth with an abscess from Alaska dated to AD 1300-1700.

Institutional, and Other Care and Treatment

The development of hospitals to take in the sick was particularly late in time. While the Romans built military hospitals within their Empire and had physicians, it was not until the Late Medieval period in Europe that hospitals developed on a larger scale. General hospitals opened to treat the sick and give charity to the poor, usually as a result of a rich benefactor feeling that it was necessary to provide such charity for their own weLl-being after death. There were also more specialist hospitals to segregate and/or care/treat the leprous (leprosaria) and tuberculous (sanatoria). For example, the first sanatorium was founded in France in 1643 but it was not until the nineteenth century that the real concept was established for isolating tuberculosis sufferers in specifically designed institutions. A healthy diet with lots of protein, fresh air, sun, and a balance between exercise and rest were the main therapeutic remedies advocated. All around the world sanatoria opened, usually at high altitudes, with those in North America, becoming very big business. Before that time, specific dietary components such as milk to increase strength and resistance to tuberculosis (ancient Greeks), the ingestion of the meat of animals with ulcerated lungs (fourth/fifth-century AD Babylonia), and hyssop and fleawort boiled in sour wine (Galen, second-century AD) were advocated.

Leprosy also invoked a reaction by communities, which suggests that like tuberculosis it was a disease which was associated with stigma. One of the reactions was to found leprosy hospitals to segregate the leprous and, although documentary sources from Medieval Europe attest to herbal and other treatments for leprosy, hospitals per se were not for treatment purposes. In Britain, over 300 leprosy hospitals were founded in the Late Medieval period, mainly between the eleventh - and sixteenth-century AD. However, by the fourteenth century foundations were declining and new hospitals tended to be established only in Scotland after that time. The diagnosis of leprosy was inaccurate, however, and generally relied on village elders, clerics, or physicians observing the facial characteristics of a suspect or the properties of their blood; this means that many people with leprosy were probably not diagnosed, while others were misdiagnosed. Likewise, treatment was also unconventional and involved the use of herbal remedies such as scabious and nettle, blood-letting, bathing at specific sites, and eating particular foods. Neither diagnosis nor treatment showed much logic or judgment but were more a reaction to a disease that was ill understood and feared.

Clearly, evidence for our ancestors developing coping mechanisms for dealing with disease is abundant and comes from a variety of sources. While some of the treatments advocated are somewhat strange, it at least shows that societies were attempting to deal with health problems.

World History

World History