‘You guys going to stay here until you’re all dead? Like to see me attack alone?’ The American lieutenant rushed towards the barbed-wire entanglement and blew a hole in it with an assault charge. ‘Come on, let’s go!’ Three hundred exhausted men of the 1st US Division, 5th Corps, death staring at them on their bitterly contested toehold of Nazi Europe, flung themselves after the lieutenant. At last the Americans began to move forward from the slaughter of ‘bloody Omaha’ beach on D-day 6 June 1944, the first day of the Allied invasion of Europe.

At 2130 on Sunday 4 June Group Captain Stagg, senior meteorologist, reported to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Forces, and his senior commanders that the bad weather, which had already forced one postponement of the Allied invasion, was improving.

A rain front over the planned assault area was expected to move in two or three hours and the clearing would last until Tuesday morning. Stagg expected the high winds to moderate and cloud conditions to permit bombing during Monday night and Tuesday. But a heavy sea would still be running and the cloud base might not be high enough to permit spotting for naval gunfire.

Eisenhower faced a critical decision. Such weather conditions would be barely tolerable but to decide on another p>ostF>onement meant that the invasion would have to wait until 19 June before the

Right conditions of moon, tide and daylight returned. The choice was between a risky disembarkation of troops or postponement - and the longer the delay, the shorter the likely duration of good campaigning weather on the Continent. Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, Commander-in-Chief Allied Naval Forces, reminded the Supreme Commander that he had to make a decision within half an hour for by then, if the invasion were to go ahead, orders must be given to the first convoys to sail. Turning to General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Ground Force Commander, Eisenhower asked, ‘Do you see any reason for not going on Tuesday?’ ‘I would say Go,’ replied Montgomery. At 2145 Eisenhower announced his decision. ‘I am quite positive we must give the order... I don’t like it, but there it is... I don’t see how we can do anything else.’

With the decision taken, the detailed plans that had been prepared over the years began to unfold. The invasion would take place along the 40 miles of coastline between the Vire Estuary and the River Ome in western Normandy. This area offered several advantages - it was near the ports in southern and south-western England, the beach-heads would be within Allied fighter range, it was near the major port of Cherbourg which, hopefully, would be captured early, and Allied air attacks on railways and bridges might be able to isolate the assault area and slow up the arrival of German reinforcements and supplies.

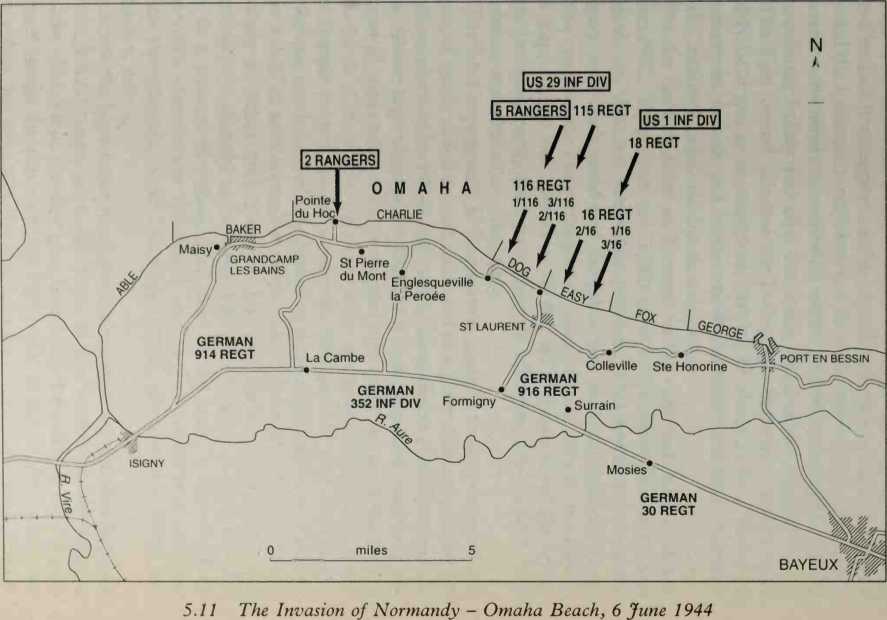

The initial assault landings were to be carried out by 21st Army Group, under Montgomery’s command, consisting of six reinforced infantry divisions landing from the sea, and three airborne divisions. On the east was the British 2nd Army and on the west the United States 1st Army. Five beach-heads had been selected - ‘Utah’ and ‘Omaha’ for the United States 1st Army; ‘Gold’, ‘Juno’ and ‘Sword’ for the British 2nd Army.

A number of factors governed the selection of D-day. A long period of daylight would enable maximum advantage to be gained by Allied air power. The moon should be nearly full to aid the airborne troops and the tide should be strong. Beach obstacles would thus be fully exposed at low water and vehicle landing craft could ground, unload and withdraw on a rising tide. The requirements of the actual timing of the landing, H-hour, also entered into the calculation.

The Allies had learnt several lessons from previous amphibious operations and these had to be considered in selecting H-hour. At Tarawa, the Americans learnt that naval fire support could not be

Relied on to neutralize beach defenses, unlocated gun positions, or to provide close fire support for the assaulting troops. Admiral Ramsay studied the full report and observed that ‘the heaviest casualties were caused by the failure to neutralize enemy positions during the period immediately before and after the touch down of the assault.’

The final period selected for D-day was between 5 and 7 June and H-hour was to be staggered, varying by about an hour from the easternmost British and westernmost American landings, because of the different tidal and beach conditions.

On the German side, an invasion in the west had been expected since 1942. To protect the 3,000 miles of coastline Germany controlled, an ‘Atlantic Wall’ was planned. This fortification existed largely in Hitler’s mind and though it was good propaganda it was never completed. Their manpower situation was also discouraging. On paper there were between 50 and 60 German divisions in the west but they rarely had more than 25 efficient, full-strength field divisions available at any one time.

The 5th Corps assault at Omaha was planned to extend over 7,000 yards of beach which curved landward in a slight crescent, flanked at both extremities by 100-ft-high cliffs rising almost directly out of the sea. Above high-water mark there was a sloping bank of shingle, in places 15 yards wide, which extended into sand dunes on the eastern two-thirds of the beach. On the remaining western third of the beach, the shingle butted against a sea wall, between 4 ft and 12 ft high.

Behind the dunes, which formed an impassable barrier to vehicles, was a shelf of sand some 200 yards wide in the center but narrowing sharply at either end. Beyond this sand shelf, the grass-covered ground rose sharply to between 100 ft and 180 ft before opening on to a plateau of rolling farm land. Four small wooded valleys extended inland from the beach area to provide natural corridors onto the plateau. Near the eastern end, there was a fifth, less distinct, exit.

Below the high-water mark the beach sloped very gently but with an 18 ft tidal range, some 300 yards of firm sand would be exposed at low tide. Here the Germans had built three bands of obstacles which would be concealed at high tide. None of the bands was unbroken but together the three formed one continuous obstacle over 100 yards wide and 250 yards out from the high-water mark at its seaward edge. The first two belts consisted of waterproofed Teller mines fixed to iron frames and upright logs and the third comprised

A series of metal ‘hedgehogs* designed to hole assault craft that had avoided the mines.

The German shore defenses at Omaha were based around 12 strongpoints though not all of them had been completed by June. Each of these strongpoints was a small complex of pill boxes, gun casements and firing trenches, surrounded by minefields and wire. Only two of the complexes were bomb-proof. Deep trenches or tunnels connected the various components and there were underground living quarters and ammunition stores. The strongpoints were mainly sited to block the valley exits from the beach though they could also cover the tidal flat and the whole beach with both flanking and direct fire. Machine-gun emplacements, weapon pits, barbed wire and minefields fortified the areas between the strongpoints. In all there were 35 pill boxes with artillery pieces of various sizes and/or automatic weapons, four artillery batteries, 18 anti-tank guns, six mortar pits, 35 rocket-launching sites, each equipped with four 38 nun rocket tubes, and 85 machine-gun nests.

There was no heavy coastal artillery in the Omaha sector and only two batteries of mobile field guns in the inunediate vicinity, but there were about 60 light artillery pieces within the strongpoints. The Allies had been informed that the defensive positions were held only by a reinforced infantry battalion, 800 to 1,000 strong, belonging to the 716th Infantry Division. Fifty per cent of these were supposed to be non-Germans. But this intelhgence assessment was wrong.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, Army Group B Conunander-in-Chief, and responsible for coastal defenses between Denmark and the Pyrenees, knew from his experience in North Africa that it was folly to use massed armor against an enemy who had air superiority. If the German army could not fight the Allies on something like equal terms, then its only chance of offering a successful defense was to fight from the strongest natural positions. The battle for the West, Rommel considered, would be decided at the water’s edge, and the decision would come within the first 48 hours of the Allied landing. He therefore wanted to move the German armored divisions forward into the coastal areas, so that at least elements of them could intervene.

But Rommel was overruled by von Rundstedt. He was only permitted to make a few moves forward nearer to the coastline. This proved to be very fortunate for the Allied troops at the Omaha beach-head. Allied intelligence estimated that the nearest German

Reserves to the Omaha sector were two more battalions of the 716th Division, but they judged that it would take them two to three hours to arrive, and then they would be able to do little more than help contain the Allied landings. A full scale counter-attack would have to await the arrival of the 352nd Infantry Division, thought to be in the St Lo-Caumont area some 20 miles farther inland, and the Allies believed that it was not capable of delivering such an attack until the afternoon of D-day.

The objectives of 5th Corps were then laid down with the aim of gaining an adequate foothold or lodgement area as quickly as possible. The assault echelons (an echelon is a formation of troops in parallel divisions, each with its front clear of the one ahead) were to break through the beach defenses within two hours of landing, and then clear the exits leading out through the valley by H + 3 hours. This achieved, 5th Corps’ D-day objective was to advance four miles inland and secure the plateau up to the river Aure, where the Corps was to be prepared to repel German counter-attacks. Later 5th Corps was to push southwards towards Caumont and St Lo, conforming with the British 2nd Army on its left flank.

Fifth Corps consisted of three infantry divisions; the 1st Division, which had seen action in the Mediterranean, and the 2nd and 29th Divisions. Since the Corp’s subsequent operations were to develop on a two-divisional frontage, it was necessary to land elements of both divisions in the assault echelons, so as to avoid having to pass one formation through another within the restricted bridgehead. There was neither sufficient shipping nor room on the beach to allow both formations to assault at once.

The Corps would then conduct its landing in four basic echelons, the two assault ones each consisting of some 15 waves of landing craft. The first echelon (Force O) and the second echelon (Force B) were commanded by the headquarters of the 1st and the 29th Divisions respectively but were made up from elements of both formations. The 2nd Division formed the third echelon, and a miscellany of units the fourth and last.

Embarkation of Forces ‘O’ and ‘B’ began on 31 May and 1 June and both were completed by 3 June. The numbers of men and vehicles involved was enormous - for Force ‘O’, the first assault echelon,

34,000 men and 3,300 vehicles were loaded into 300 landing craft. Two battleships, three cruisers, 12 destroyers, 33 minesweepers and 105 other ships supplied the escort, minesweeping and fire-support

Requirement. In addition, 600 vessels of different types were ready for a variety of support and service work. The main convoy of Force ‘O’ left Portland harbor in Dorset on the afternoon of 5 June and made an uneventful crossing of the English Channel under continuous Allied air cover.

At 0300 the armada arrived at a point 12 miles off Omada. The wind gusted between 10 and 18 knots and waves were 3 ft to 4 ft high. Into this swell the assault craft were unloaded from larger ships. Some were winched down fully loaded, but to get into others soldiers had to scale the scramble nets over the sides of the parent ships. This was a hazardous operation as the craft were tossing and bucking in the heavy sea. The men were heavily laden - each soldier was equipped with weapons, a rubber life-preserver, a gas mask, a first-aid kit, entrenching tools, a canteen, knives and rations and extra anununition and explosives.

Ten small craft sank almost at once, throwing 300 heavily laden men into the sea. The assault craft circled the transport area, getting into formation. As dawn lightened the sky, the craft edged towards the beaches. Discomfort followed the soldiers as waves sloshed over the blunt bows of the landing craft and they had to bail out with their helmets. Seasickness added to the misery.

The sea also took a toll of the guns and armor that were to follow the assault craft. Thirty-two amphibious tanks were launched too early into the swell and sank within minutes. Some crews escaped, others drowned in their vehicles. Ninety-six tanks were planned to follow the soldiers onto the beaches - a third of that number had now been lost without ever coming under fire. The DUKWs that were to ferry support artillery ashore also ran into difficulties. The small, heavily laden craft foundered - the 111th Field Artillery Battalion lost all but one of its 105 mm howitzers and the 16th Infantry Cannon Company and the 7th Field Artillery fared little better.

With 40 minutes to go to H-hour, when the troops would reach the beaches, the Allied aerial and naval bombardment of the enemy defenses reached a climax. The Allies had a massive air superiority on D-day. A total of 3,467 heavy bombers, 1,645 medium, light and torpedo bombers, 5,409 fighters and 2,316 transport aircraft were stationed in England on 6 June. Against this the Germans could muster only 319 aircraft, of which 100 were fighters. Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, Commander of Luftwaffe Air Fleet III, had requested more aircraft before D-day - the Luftwaffe simply could not spare

Any from the defense of Germany’s industrial centers. German naval patrols had been canceled on 5-6 June because of bad weather and the ships stayed in port. In fact the German navy did not consider the weather suitable for an invasion and, because they had no weather stations in the west, they were unable to detect the improvement in the weather noted by the Alhes. German E-boats did approach the Allied fleet by accident but the mighty steel shield of warships that protected the invasion force was impenetrable. One German rating, on seeing the Allied force, said in astonishment that ‘It’s impossible. There can’t be that many ships in the world!’

At Omaha, 500 heavy bombers of the US 8th Air Force mounted a concentrated attack on the German defenses. The US battleships Texas and Arkansas poured 3,500 shells into the enemy positions from their total of ten 14-in, 12 12-in and 12 5-in guns. A variety of fire-support craft softened up the landing areas. But even this did not convince German High Command that the invasion point was between Cherbourg and the Seine and not the Pas de Calais area which, to strengthen the illusion, the Allies had bombed extensively in the days leading up to 6 June.

In the assault craft the cold and miserable vanguard of the invasion, bailing frantically to remain afloat, paused to look up and cheer the flying shells that were to destroy the German coastal defenses. The landing craft moved closer and closer to the shore of occupied Normandy and still no response came from the enemy defenses.

It was a silent prelude to disaster. The naval bombardment had overshot many of the front-line enemy positions. Some had been neutralized but only temporarily. The final aerial bombardment did not deliver a single bomb on the beaches - for fear of hitting their own men the aircraft crews had delayed a few seconds in dropping their bombs. They fell three miles inland. The landing craft, in a strong lateral current, had tended to drift eastward: the landmarks, seen so often in aerial photographs and in training exercises, were shrouded in smoke and dust and early morning mist. And so the troops, trained for specific tasks in their planned landing areas, found themselves in a confused and unexpected situation.

But this was the least of their immediate problems. The German shore batteries opened up, crashing into the bobbing, awkward landing craft. Artillery, mortars and machine-guns thundered all along the four-mile stretch of Omaha beach. Those units whose job it was to ensure that the successive waves of assault craft

Could beach safely and disembark their men and equipment on the rising tide suffered badly. The special Engineer Task Force was responsible for clearing gaps through the belts of obstacles during the first half-hour of the landing. Only five of the 16 assault ferries carrying the Engineers landed in the correct sectors and of these, three of the teams had no infantry or tank support. Sixteen bulldozers were to have come ashore with the task force - only six reached the beach and three of these were quickly disabled by artillery fire. Much of the equipment needed to mark lanes through the obstacle belts was lost or destroyed.

To add to the Engineers’ problems they came in behind schedule and became mixed up with infantry, some of whom sought shelter behind the obstacles the Engineers were intended to blow. The Germans singled them out for special attention, with sniper fire detonating the mines fixed to the obstacles while the Engineers were working on them and mortar fire detonating rows of mines. At the end of the day there were 50 per cent casualties among this special unit.

Despite the difficulties, the Engineers managed to clear six lanes through the belts of obstacles before the incoming tide submerged them. Four of these lanes were in the 16th Regiment’s sector and two in that of the 116th Regiment. But only one of these lanes could be marked and this created casualties and confusion as waves of assault craft, unaware of the situation, approached the areas. One craft struck a mine and disintegrated, showering the Engineers with debris and spreading blazing fuel over the water.

On 5th Corps’ right flank, the invasion plan was for the 116th Infantry Regiment to land four companies in the first assault wave on each of their four beaches - code-named Dog Green, Dog White, Dog Red and Easy Green. A Ranger Company was to land slightly farther to the right on Charlie beach and from there it was to assault a strongpoint just to the west of Vierville. The 16th Infantry Regiment should also have landed four companies in the first assault wave in Easy Red, Fox Green and Fox Red.

Because of the general eastward drift of the landing craft few touched down in the correct sectors and sub-units became hopelessly mixed. Few landing craft made dry landings, most of them grounded on sandbanks up to 100 yards from the beach and in some places troops were disembarked into water that was neck deep.

F and G Companies came ashore on Dog Red and Easy Green.

Although under heavy fire and disorganized by landing in the wrong place, many of them crossed the 200 yards of tidal flat to shelter behind the sea wall and shingle. Those who stopped at the water’s edge were under direct German observation and suffered casualties. The right wing of 5th Corps’ assault wave had practically disintegrated and the four companies of the 116th Infantry Regiment were no longer a fighting force. A Company had been cut to pieces on the shore line, F Company was disorganized by heavy casualties, scattered sections of G Company were trying to find their correct sector and E Company had veered widely off course, landing on the eastern extreme of the 116th Regiment, on the left flank.

To the west of the 116th Regiment, on the extreme right flank of Charlie beach, the 2nd Ranger Battalion had suffered severely. Their objective was an enemy strongpoint to the west of Vierville. One of their two landing craft was sunk by artillery fire and the other came under direct machine-gun fire as soon as the ramp was lowered. By the time the soldiers had reached the base of the cliff, 200 yards from the water’s edge, only half the 65-strong unit was still alive. By nightfall, only 12 remained.

There were heavy casualties on the left flank, in the 116th Regiment’s sector, but the majority of the supporting tanks had got ashore. Four tanks landed on Easy Red, a mile-long beach marking the junction point of the 116th and 16th Infantry Regiments, but only about 100 men landed with them - unfortunate for the Allies, for here enemy resistance was light. E and F Companies were scheduled to land on Easy Red but the bulk of both companies drifted too far to the east. The result was that only elements of these companies, together with part of E Company of the 116th Regiment, came ashore in the right sector in the first assault wave and these were bunched on the extreme eastern part of the beach.

Some of the troops were disembarked in waist-high water but then had to cross a deep channel to get to the beach. This pulled them even fanher to the east and though casualties were light, with only two men killed, most of their heavy equipment such as flame throwers and mortars and some personal weapons were lost. Others landing slightly farther to the east were less fortunate - not only were they disembarked in deep water but they came under heavy fire. Only 14 men reached the shingle.

Stiff enemy resistance, faulty navigation and delays contributed to the critical situation that was now developing on Fox Green.

Two companies from the 116th Infantry were scheduled to land in the first assault wave but the bulk of four companies, including elements of E Company of the same regiment, landed hopelessly intermixed in a comparatively restricted sector. Few casualties had been incurred in the final approach to the beach but as soon as the leading landing craft lowered their ramps and disembarkation got under way interlocking enemy machine-gun fire swept the water and inflicted heavy casualties. The survivors struggled to the water line and here, with most of their officers dead or wounded, they stopp>ed.

I and N Companies of the 16th Infantry Regiment, which should have formed the first assault wave on Fox Green, were delayed - and they missed the disaster. I Company drifted widely off course and were an hour behind schedule. N Company was 30 minutes late and landed beyond the eastern limit of Fox Green. The company lost a number of men at sea and during the landing but it disembarked at a point where the tidal sand reached almost to a steep escarpment. This was the only company, of the nine that formed the first assault wave, that was ready to act as a unit.

At 0700, 30 minutes after the first assault wave had landed, a second group of five foUow-up waves approached the beaches. These included the support battalions of the two leading regiments and was timed to go ashore at 0740. None of the follow-up assault waves arrived under the conditions that were expected. The tide had risen nearly 8 ft and now covered most of the beach obstacles. Only six lanes through the obstacles had been cleared and these were still not properly marked. The initial assault waves had not advanced beyond the sea wall or shingle and neither the surviving tanks nor the infantry from the first wave were in a condition to provide more than spasmodic covering fire. Nowhere had the enemy defenses been neutralized.

The troops in the second wave were organized, briefed and equipped to do no more than mop up any enemy positions that had been by-passed by the first wave. They were then to move inland, by boat loads, to their respective battalion assembly areas. Only a few sections of the second waves had special assault equipment - flame throwers, demolition charges and bangalore torpedoes for clearing lanes through minefields once ashore.

The troops in the second waves, as they approached the shore, could see the carnage wrought among the first wave. Debris from

Sunken assault craft bobbed among half submerged bodies and struggling survivors. Broken or discarded stores, weapons, lifejackets, equipment of every kind littered the shore line. Silent, wounded soldiers were grouped among the desolation, many in severe shock. One sergeant recalled a ‘terrible politeness among the more seriously injured’ and a soldier of the 741st Tank Battalion saw a man sitting at the water’s edge, oblivious to the machine-gun bullets that spattered about him, ‘throwing stones into the water and softly crying as if his hean would break.’ Medical orderlies, there to treat the wounded, did not know ‘where to start or with whom’.

On the right wing, in the 116th Infantry Regiment’s sector, the 1st Infantry Battahon had landed only A Company in the initial assault wave; the other three companies in this wave belonged to the 2nd Infantry Battahon. The 1st Battalion’s three remaining companies were to come ashore in the second wave on Dog Green in echelon formation at ten-minute intervals. They assumed that A Company’s assault wave had cleared most of the enemy positions.

At 0700, B Company started to come ashore but it was badly scattered over an area extending to nearly a mile on either side of its intended sector. A few assault craft beached in the correct area but were subjected to the same heavy fire that had decimated A Company 30 minutes earlier. The survivors of B Company struggled ashore to mingle with those of A Company along the shore line. Only three widely dispersed groups on the flanks played any effective part in the subsequent battle.

C Company was scheduled to land directly behind B Company at 0710. A major navigational error prevented it from doing so - and it was saved the disastrous fate of B Company. The company came ashore 1,000 yards to the east on Dog White beach. One of its six assault craft became entangled on the mined obstacle belt and it took 20 minutes of gentle maneuvering before it got free. The remaining five assault craft approached the shore in reasonably good order but the vessel carrying the special assault equipment capsized in the surf when its ramp jammed and the entire load was lipped into 4 ft of water. The unit recovered from this set-back and suffered only six casualties in disembarking and crossing the sand, largely because smoke from grass fires in the escarpment obscured enemy observation. C Company moved up to the sea wall and started to reorganize.

At 0720 D Company began to disembark having lost two assault

Craft, one swamped and the other hitting a mine. The remainder of the company got no farther than the shore line, having come under fire as soon as they disembarked. Most of the heavy support weapons were lost. To add to the disruption, the three assault craft carrying the battalion command group, the Headquarters Company and the Beachmasters party for Dog Green were widely scattered several hundred yards to the west. They came in directly under the cliffs and suffered heavy casualties in doing so. They stayed in the same position for most of the day and played no part in co-ordinating the scattered renmants of the battalion.

The 2nd Infantry Battalion had landed three of its companies in the initial assault wave - now only G Company survived as a fighting unit. Machine-gun fire ripped into the ranks of the supporting H Company and of the battalion headquarters as the ramps were lowered. Men scrambled for shelter behind disabled tanks near the water’s edge. The battalion commander, together with his command post and elements of H Company, braved the fire, running up the open beach to the shingle bank where they joined the leaderless survivors of H Company. Because of the faulty radio communications it was over an hour before further progress could be organized. Eventually an attack by about 50 men was moimted against the enemy positions in and around Les Moulins, but it was beaten back to the crest of the shingle bank.

While this was in progress, the four sections of G Company, trying to move along the beach to get near their objectives on Dog White, gradually lost cohesion. One by one individuals or small groups stopped to take cover, only to become mixed and separated as they progressed westwards along the shingle bank crowded with survivors of other companies. By the time the remnants of G Company had reached their correct sector at about 0830, the main action was already over.

The 3rd Battalion of the 116th Infantry Regiment was scheduled to arrive directly behind the 2nd Battalion on Dog White, Dog Red, and Easy Green between 0720 and 0730. But the battalion was ten minutes late and came in well to the east on Easy Green and Easy Red along a thousand-yard frontage. Only a few scattered elements of the first assault wave had landed in this sector. K and I Companies came in behind them in close formation on Easy Green, and suffered only a handful of casualties in crossing the tidal flat to the shingle, but having arrived there safely they appear to have become inunobilized.

L Company disembarked on either side of the junction between Easy Green and Easy Red, where they met only light enemy fire, which many men seem not to have noticed. M Company landed farther to the east on Easy Red and, encountering enemy fire on first disembarking, they stopped at the water’s edge. Eventually, when the rising tide began to push them forward, the whole Company moved to the embankment as a body and, as one of them later remarked, ‘the Company learned with surprise how much fire a man can run through without getting hit.’

Although the enemy defenses had not been breached, the second assault group suffered much less severe casualties than the initial one. Altogether five of the eight companies of 116th Infantry Regiment were capable of developing and holding a precarious toe-hold which they had established. Troops who were demoralized and lacked inspired leadership found this supplied when, at 0730, the Command Group of the Regiment, which included the assistant divisional Commander Brigadier General Cota and Colonel Canham began to land on Dog White. Both men were fearless soldiers and could not have arrived at a more opportune moment nor at a better place to influence events. To their left troops were crowded along the embankment of a few hundred yards, while the main Ranger contingent was about to land in the same area. Ahead of them, behind the embankment, smoke from burning grass obscured the enemy’s view and rendered his fire largely ineffective.

The experience of the 16th Infantry Regiment was similar to that of the 116th. Although the initial assault wave all landed on Fox Green, leaving the large 2,000-strong force on Easy Red beach with only a handful of infantry operative, the second group started to land, and casualties were high. The main problem was the dislocation of command posts, faulty landings, casualties, the loss of radio sets and the physical difficulty commanders experienced in imposing control. Except for those inunediately around them, they could exert little influence over the many men lying against the sea wall - a shelter they were all too reluctant to leave. Behind them the troops could see successive waves battling through the same fierce defense they had been through and the bodies of dead and dying comrades, and in front of them lay the enemy and a beach flat littered with minefields and wire obstacles.

The situation looked critical and further vehicles and support weapons could not come ashore until the exits had been cleared.

But slowly, desperately slowly, inspired leadership and individual heroism began to turn the tide. General Cota and Lionel Canham, the latter already wounded, walked up and down the beach oblivious to enemy fire and bluntly directed officers and NCOs to get their men moving. Slowly groups of men, often from different units, and in other places units of company size, started to move forward supported by the few remaining tanks. Behind Easy Red beach an engineer lieutenant and a wounded sergeant walked forward under fire to clear a lane through the wire obstacles. Their task done they returned and looking down in disgust at the men huddled behind the shingle, exhorted them to get forward before they were killed where they lay. Advances were made in a world of smoke and confusion, each group isolated from its neighbors. An impetus developed, however, as successive penetrations brought a slackening of enemy fire.

The most significant advance in the 116th Regiment’s sector came from Dog White beach. Here C Company and the 5th Ranger Battalion were spurred forward by General Cota at about 0750.

German defenses in this area consisted of lightly manned weapon pits connected by deep trenches sited just on the crest of the escarpment. The machine-guns were mainly sited to provide flanking fire down other sectors of the beach, rather than to deal with a direct assault. On the opposite side of the sea wall there was a double apron wire obstacle which had to be breached before the infantry could get through. After an initial setback, a gap was eventually blown by a bangalore torpedo and the infantry started to filter through under cover of heavy smoke from the grass fire drifting eastward along the face of the escarpment.

The leading infantrymen were joined by others who had cut their way through the wire and together they moved forward to the high ground giving access to the plateau. Progress was slow here through fear of mines, and the company advanced in colunm following an indistinct track. On gaining the top of the escarpment the enemy positions were found to be unoccupied and, after suffering only six casualties since leaving the shelter of the sea wall, the advance was resumed for a farther 200 yards when, still moving in column, the company encountered machine-gun fire from a flank and went to ground.

At 0810 the 5th Ranger Battalion, without knowing exactly what C Company was doing ahead of them, crossed the beach flat after

Blowing four lanes through the wire and started to climb the escarpment. Heavy smoke forced some of the men to put on their respirators and contact was lost between the various sub-units. However, for the loss of only eight men, the few enemy positions still holding out on the edge of the escarpment were overrun, and, after pausing to reorganize, the Rangers resumed their advance.

By 0830 a penetration 300 yards wide had been made and the last groups of infantrymen were leaving the sea wall. It was not in itself an advance of great significance but similar actions, frequently on an even more reduced scale, were being conducted all along the beaches. These isolated penetrations were then gradually linked together, expanding the bridgehead laterally and, what was of equal importance, giving it some depth so that further reinforcements of both men and equipment could be brought ashore as the beach exits were first cleared and then developed.

On the 16th Regiment’s front, a gap opened up by G Company became an exit for movement off the beach during the remainder of the morning. The Regiment’s command group landed in two sections at 0720 and 0815. The second section included Colonel Taylor who got his disorganized and leaderless men moving with terse instructions: ‘Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die - now let’s get the hell out of here!’ As soon as the engineers had cleared gaps through the wire obstacles and scattered minefields, the infantry were organized into haphazard groups and sent forward under the command of the nearest available officer or NCO. As they moved forward through the gap, there was intermittent enemy fire from both flanks and the already congested route became a scene of even greater confusion as leaderless groups stopped to shelter below the crest.

Strenuous efforts by the officers who had landed with the various command groups in the later waves encouraged the troops forward onto the plateau and gradually the bridgehead was extended. Progress inland was aided by a few isolated but determined groups of Rangers who had landed to the flanks of the main assault, and then fought their way forward unaware of what was happening elsewhere. As the penetrations which had been made between 0800 and 0900 started to link up, a new but still fragmented phase of the battle began. German defenses along the immediate coastline had begun to crumble and there were no significant reserves available to the enemy in the Omaha sector. A more immediate threat to the Germans came

On the flank of 5th Corps attack. Here the British 2nd Army had broken through the German defenses in a number of places, and to the west, the American 7th Corps was firmly ashore with men and vehicles pouring across the beaches almost unhindered.

The inland batde behind Omaha developed into three generally unconnected and largely uncoordinated actions around Vierville, St Laurent and Colleville. Although there was only scattered resistance from small but determined enemy groups, seldom as much as company strength, progress was slow for a variety of reasons. Little fire support was available since most of the tanks and heavy support weapons had been lost during the landings, vital communication links were missing, units were frequently still hopelessly mixed, and control amongst the thick hedgerows was extremely difficult.

By 1100, however, Vierville had been cleared after a frontal attack by two battalions of the 116th Regiment, who then tried to extend the bridgehead laterally to link up with the Rangers who had landed farther to the west. By late afternoon this advance had been halted and Colonel Canham decided to withdraw and concentrate on the defense of Vierville, where the scattered Engineers, with only a quarter of their equipment, struggled to open up the beach exit giving access to Vierville. East of the Les Moulins valley, the 3rd Battalion of the 116th Regiment fought their way forward in small groups until they were stopped just short of St Laurent. Farther to the east, two battalions of the 16th Regiment fought a series of confused and fragmented actions in an advance towards Colleville, which was halted short of the town by a local German counter-attack.

At sea, the 115th Infantry Regiment had been held as a floating reserve only to be committed if the situation became critical. The desperate situation which had developed during the 116th Regiment’s landings on the right wing of 5th Corps assault demanded their conmiittment so the 115th Regiment was ordered to land at H+4 (1030) to give immediate support. The same eastward drift which had disrupted the earlier assault waves dislocated the landings of the 115th Regiment, Pulled eastward by the incoming tide sweeping up the English Channel, the Regiment landed on top of the 18th Infantry Regiment in the process of disembarking east of St Laurent. It was not until early afternoon that the confusion on the congested beaches could be sorted out and the 115th Regiment headed for its assembly area south-west of St Laurent. After an

Unsuccessful attempt to take the town, the regiment halted short of the St Laurent-Colleville road.

The 18th Infantry Regiment, whose disembarkation had been disrupted by the unscheduled arrival of the 115th Regiment in their rear, was tasked with taking over the 16th Regiment’s D-day objectives. However, because of delays and enemy resistance, their orders were changed and it was directed onto the high ground beyond the St Laurent-Colleville road to fill a gap between the 16th Infantry on the right, but at dusk it had not managed to reach the road.

At the end of the day 5th Corps had established two footholds, the first in a narrow sector between St Laurent and Colleville, nowhere more than a mile and a half deep; the second, slightly farther to the west, around Vierville. The cost of these modest gains had mounted to 2,000 killed, wounded and missing, together with the loss of a large amount of equipment which included about 50 tanks and 26 artillery pieces. The whole of the landing area was still under enemy artillery fire and of the 2,400 tons of supplies planned to be onloaded during D-day, only about 100 tons had actually arrived. Beach obstacles were only about a third cleared, even after a low tide during the afternoon had enabled the Engineers to resume work on them; beach exits had not been developed, nor had the essential beach organization, necessary to ensure the orderly handling of successive landings, been properly established.

The principal cause of 5th Corps’ setback was the unexpected degree of enemy resistance. Not only were prisoners taken from the 726th Regiment which was known to be in the area, but also from the fully combatant 352nd Division whose presence on the coast came as a complete surprise. How much of the 352nd Division was actually in the Omaha area is not known - certainly not the whole formation, since elements of it were encountered as far east as Bayeux in the British 2nd Army sector. The division appears to have been moved into the area between Grandchamp and Arromaches - in order to stiffen the second-line coastal formations deployed within the immediate beach defenses. In this manner, all the prepared strongpoints and their various interconnecting weapon pits were fully manned and the artillery of the 352nd Division, consisting of three field and one medium battalion, was at least in part able to support the German troops confronting the Omaha landings.

Had it not been for the massive assistance of the Allied navies and air forces during this critical period of 5th Corps’ landing, it

Is doubtful whether the shaken and depleted troops of the assault waves would have been able to recover, reorganize and then develop an offensive which was to deepen and widen their bridgehead in the succeeding days.

Omaha is a story of near disaster but no shame. Largely unseasoned troops, subjected to all the hazards of a vast and complex amphibious operation, further compounded by unfavorable weather conditions and stubborn opposition, were initially near paralysed by shock but, under the shield of fire provided by the allied navies and air forces, rallied and resumed a dogged offensive.

World History

World History