When I first saw the monastery it was intact, an ancient and magnificent building set on the top of the steep slopes of Monte Cassino. It dominated the surrounding countryside. As we drove towards the battlefield, at every turning, at the top of every crest, there was the monastery getting bigger and clearer. On a cold February morning in 1944 it presented a noble sight with the pale winter sun shining on the glass of its windows and the great towers and dome outlined against the grey sky.

During the next two weeks, at a comparatively safe distance from the monastery and the town of Cassino, I acted as a supernumary liaison officer, and was a spectator, removed from the fierce struggle that was taking place on the hills across the Rapido valley. Some two or three miles away from our vantage point we could see and hear the battle being waged in the ruined town, among the rocks and scrub on the ridges under the shadow of the monastery, against the background of Monte Cassino, and, to the north, the towering snow-capped peak of Monte Caira where the French wrestled with the elements as well as stubborn German defenders.

Under a clear sky on the morning of 15 February and with token opposition only from the Germans, an armada of bombers made their appearance over the monastery and for four hours wave after wave of bombs pulverized the building; the planes dropped their bombs from heights between 18,000 ft and 10,000 ft. It was an impressive

And awe-inspiring spectacle. Even from our remote vantage point we found it difficult to envisage anyone surviving the punishment being meted out. Then, to add to the destruction, the Allied artillery began to batter away as soon as the bombers had returned to their bases. By now the monastery looked like a gigantic decayed tooth and in our innocence most of us thought it would never dominate the valley again. We were wrong. Without scruple, the Germans were now able to use the ruins for defense.

German paratroopers constructed loopholes in the ruined walls from where they could fire in several directions. Artillery and mortar observers kept a ceaseless watch from posts that gave them a perfect view over the terrain below, the ground over which Americans, British, Indians and Poles hurled themselves against defenses until the monastery was abandoned on 17 May 1944.

On 7 March the call came for me to join my battalion, 2/7th Gurkha Rifles, which was holding a position on the hills north of Monte Cassino. The journey forward was on foot and it is etched clearly in my memory. The track up the hills, little used by day, was the life-line of the battalions from 4th Indian Division that were holding the sector around Snakeshead Ridge. Up and down this crude path worn out of the mountainside, went everyone and everything. New, clean soldiers going up, prematurely old bedraggled men returning; some wounded, others acting as escorts to mules. The mules were moving in both directions, being urged on by Italians, Indian and the occasional British voice. How we depended on those mules in Cassino! There was no other way of getting rations, anununition and other stores up the mountains to the forward positions. It was a dangerous, uncomfortable walk.

The noise of gunfire never stopped. Far behind Mount Trochhio, on the south side of the valley, we could see the flashes of the Allied guns. Ahead we could hear the thump of the German artillery replying, and the sound of tearing silk as the shells flew above our heads in both directions. Occasionally a shell or mortar exploded on the rocks nearby or in a ravine which magnified the noise: no wonder that the climb seemed an eternity though probably it took us less than three hours to reach battalion HQ.

Mules and men, eventually we arrived at our various destinations. The journey up was over. Little did I guess that it would be five weeks before I walked down that trail, all hope of victory gone, our battalion having suffered many casualties, and not one inch nearer

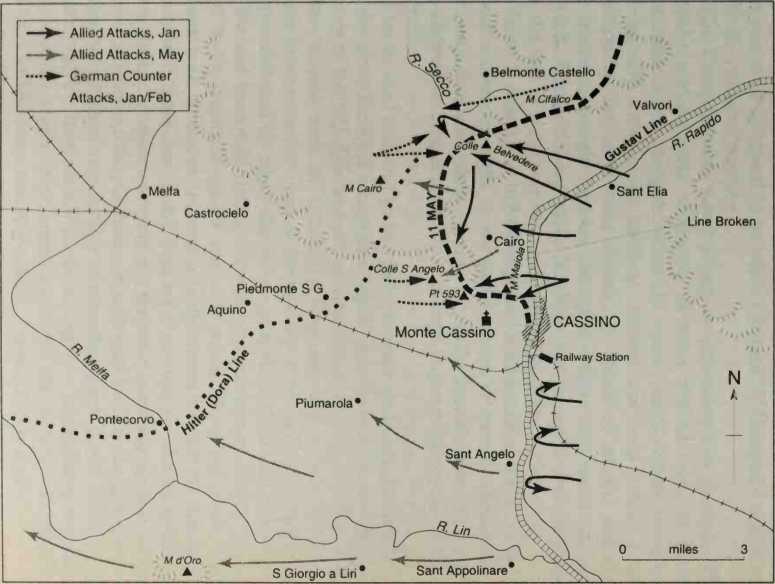

5.10 The Battle for Cassino, January-May 1944

That battered hulk of a monastery. Within those five weeks, two fine and experienced Divisions, one from New Zealand and the other, the 4th Indian, were to take such a hammering that neither formation ever reached maximum effectiveness again. Fortunately the future was not to be disclosed to us when I joined ‘A’ Company which was then in a reserve position.

The Company was not holding or defending any ground. The Gurkha soldiers were sheltering in holes behind rocks or beside man-made stone ‘sangars’ from the snow, sleet, winter wind and the equally unwelcome shelling. It was not long before I had constructed my own stone shelter, my place of refuge, and thus we stayed seemingly forever, though my diary tells me it was only a week. Rarely did we move far from our cramped shelters unless for the call of nature or for some pressing military chore.

Visits to toilets had to be postponed until evening. Then, at dusk, it was a common sight to see small groups of bare hindquarters in the semi-darkness, their owners fervently praying that they might be allowed to complete the proceedings in peace before the shelling started.

Our tactical role was to be ready to move up to reinforce any one of the three forward companies which were in position on the early slopes of the hill. Fortunately no one attacked those localities while I was serving with ‘A’ Company. This was just as well, because a move forward in full view of the monastery by day would have been impossible and by night the path would have been difficult.

We had been told that a third attempt to capture Monte Cassino was to be launched under the code name ‘Bradman’, but winter struck with all the violence of a fresh enemy so that the attack was postponed from day to day because there was no chance of aircraft even flying, let alone carrying out pinpoint bombing against Cassino town. Friend and foe, German, British and Indian, clung to exposed positions on those mountains during the worst storm in an Italian winter which held us all in its icy grasp. Long-drawn-out days, followed by nights of activity meant that the morale and physique of our Gurkhas was severely tested. I wrote in my diary:

Each night we pray that the following morning will bring a change in the weather, a respite from the rain and snow and the endless vigil that is never a quiet one because the whine and crump of the guns and mortars continue by day and night.

As day succeeds day, anxiety about the next attack has changed into a desperate longing to do anything rather than sit for ever undergoing an ordeal that tests minds and bodies alike.

Such a winter could not go on for ever, even at Cassino, and on 13 March the sky began to clear and the prospects looked brighter. We were told that the long-postponed attack was due to begin on the 15th morning: it was to be preceded by a bombardment of Cassino town by over 500 bombers. Next day dawned clear and at 0830 wave upon wave of bombers arrived, to begin pounding the town which was soon shrouded in billows of smoke and dust. It was a terrifying exhibition, even to us cowering down in our foxholes below Point 569. After a few minutes I felt like shouting - ‘That’s enough!’ but it went on and on until our ear drums were bursting and our senses befuddled. Several bombs fell astride the company position and I found myself shouting curses at the planes.

It’s no fun being bombed by anyone, but the feeling of bitterness at being bombed or shelled by your own side is beyond description; the sight of friends killed or mangled by the mistakes of friendly supporting arms arouses the deepest of emotions in the hearts of front-line soldiers. That evening I wrote in my diary: ‘What an inferno is Cassino now! Dear God - take pity on those men, if there are any survivors in the town, which I doubt.’

In spite of that terrible ordeal, many German paratroopers survived amongst the collapsed walls and the deep craters caused by the bombs. The German High Command decided to stand firm and, although casualties were heavy, they had been less than expected in proportion to the damage caused by the aerial bombardment. The battle went on. Next day, Maj. Beckett would not let us carry out the mission which had been given us by brigade HQ. Already he had seen too many costly attacks, all of which had ended in failure. Moreover, he was deeply concerned about the safety of Castle Hill itself: an active fighting company of Gurkhas near at hand and ready to help his defenders would be of far more use than another broken band of men who, he knew, would eventually trickle back like their unfortunate predecessors. He refused to let us commit suicide and told brigade HQ accordingly. As a consequence, I lived to write this story.

Later that afternoon a direct hit by a heavy German shell caused one of the castle walls to collapse, engulfing and burying several

Essex soldiers under the rubble. Without hesitation their comrades, British, Indian and Gurkha, began tearing at the stones in an attempt to save their lives. After a few minutes came German paratroopers from foxholes, some only 75 yards away, to join in the rescue operations side by side with our soldiers. In the middle of the Cassino battle there began an unofficial and very local ‘ceasefire’. Friend and foe worked together, talked and exchanged cigarettes. My company commander spoke German fluently and he learnt that the enemy’s view of Cassino was very similar to ours - it was Hell, the weather bloody, and the end impossible to predict.

It is not surprising that this incident remains clearly in my mind, truly an extraordinary commentary on the senselessness of war. My Gurkha orderly summed it up by saying that the ‘Dushman’ (enemy) were so like ‘our Sahibs’ that he wondered if there had not been a mistake somewhere! Why were we not all fighting the Japanese instead? However, his comments and the rescue operations were brought to an abrupt end by the Allied artillery which, for some inexplicable reason, opened up: the German snipers scuttled back and almost as if someone had said ‘Let battle commence,’ we were shooting away at one another once more. A few men were never released from the rubble.

I was ordered to return and brief ‘A’ Company who were still waiting at the foot of Castle Hill. Not wishing to retrace my steps along the slippery path at the top of the deep ravine, I sought another route. I met four Indian soldiers, Sikhs, who were hiding behind some rocks on the stony hillside. Their faces reflected fatigue and cold. I greeted them cheerfully, even jauntily, but their hearts were heavy. I asked them the quickest way down to the bottom of the hill. One huge Sikh replied that there was a short cut along the ridge but on this they had lost several men from accurate sniper fire. The alternative path that would take longer, was the slippery precipitous mountain track that I had used before. ‘One way you get shot. Sahib, the other you slip to your death.’ And he grinned without humor.

Being impetuous and wishing to carry out my mission as soon as possible, I decided to take a chance and dash down the track that snaked its way along the ridge to the base of the hill. I waited and waited. All was quiet. Nothing moved on the path below. Nothing appeared to be moving in the town - indeed there had been a lull in the fighting for some time although, behind me, the sound of battle around the castle continued as fiercely as ever. I rose to my feet at

The top of the hill and charged down the track: nothing mattered but to get to ‘A’ Company. It seemed as if I was going to be lucky when something flicked off my black side-cap as I threw myself behind a rock. I lifted my head and saw the bullet mark. The bullet had only just missed my head. Something had prompted me into diving for cover. It was a cold day, but in a second I was covered in sweat. Cold sweat. Everything seemed to stop: the noise of battle, the guns. Probably less than a minute or two passed. It seemed like an age. I crawled forward and willed myself to make another dash. I prayed with great sincerity, prayed for speed. I prayed that the sniper would think I had already been hit. Into the open, zigzagging down the track at the fastest speed I had ever attempted. Once again the crack, crack, a blow on my haversack and then the safety of another rock. Breathless, I lay as dead until a glance at my watch spurred me on, this time to safety. The Gurkhas welcomed me, surprised to find that I was alive because they had seen me drop twice on the track above.

It had been an exciting day, but it was not yet over. While the company remained at the foot of Castle Hill in close support of the besieged garrison, I was told to make my way through the town and report to brigade HQ to act as liaison officer and, possibly, return with fresh orders. After dark my Gurkha orderly. Rifleman Rambahadur Limbu, accompanied me as we scrambled a way down to the battered Cassino below us. It was not long before I realized that the landmarks that had appeared to be so prominent in fading daylight, from an observation point on the hill, were not nearly so easy to find in pitch darkness among rubble and ruins. After about 10 minutes I was convinced that we were lost. Unfortunately, Rambahadur and I could not agree on the direction we should be taking. We appeared to have gone round in a complete circle but Rambahadur had no doubts whatever: he was sure he knew the way and so, against my better judgement, I agreed to let the Rifleman lead. The town, or the remains of it, was strangely quiet after a day of close-quarter fighting when the noises of machine-guns and grenades had continued to pay testimony to the bitter struggle that was being waged in Cassino.

The two of us shuffled and groped an uncertain way around walls, skirting bomb craters, and scrambling over piles of stones. Occasionally we heard voices or smell cooking which wafted out of the darkness from improvised cellars and hiding places. It was quite

Impossible to tell who was friend and who foe: occasionally we saw movement at a distance. Suddenly a dark form appeared in front of Rambahadur and challenged him - in German. As Gurkha and German stood frozen in mutual surprise, I fired at the enemy sentry with my tommy-gun, saw him drop, hit by the burst of &e. We dashed down the remains of an alleyway to throw ourselves behind a wall. Within seconds, several Germans, who had been cooking or eating their evening meal below ground, were shouting furiously at each other and shooting at random. Fortunately no one came to look for us and after about five minutes all was quiet.

This time I took the lead and soon we recognized one of the lost landmarks and, without any further incidents, located brigade HQ. Here we were told to rest but although I was near the end of my tether, the clamor of battle and the nervous strain was too much for me: I could not sleep so back I went to the improvised Operations room where the brigadier informed me that ‘A’ Company would be returning before dawn. I was to guide them to a quarry nearby which was to be our temporary position until further orders. Rambahadur and I spent some considerable time searching for the best route before meeting them at the outskirts of the town. There was no sleep for any of us that night.

‘A’ Company had been withdrawn into reserve because a German force had infiltrated its way down the large ravine behind Castle Hill in an attempt to isolate the British defenders by cutting off supplies of food and ammunition. The quarry afforded us some protection from intermittent shelling and mortaring which increased in intensity during the afternoon. As darkness fell, the Germans rushed up to hold a sector and, for the rest of the night, both sides fired indiscriminately at one another without any apparent gains in territorial possession. The next day, 21 March, proved to be just as dangerous - the pressure never relenting for one moment. Throughout the morning the Germans kept up their shelling of our position while we tried to construct stronger defenses and to cover any gaps with mines. By now we were so exhausted that even sleep became impossible. I have never been a good sleeper and I was so wound up that I thought madness was close at hand even if I managed to survive German fire and bullets. Nature eventually saved me when I was going round the company’s positions after three sleepless days and nights. My legs buckled under, I hit my head and passed out. At the Regimental Aid Post, the Indian doctor who had

Already supplied sleeping pills without success, soon diagnosed my comotose state. Events did not let me sleep for more than six hours, but I was restored to sanity again.

So it went on, the merciless shelling and mortaring that claimed many victims. ‘A’ Company was near the end of its tether. Our Gurkhas’ normal resilient cheerfulness, their toughness, their fatalistic attitude towards life generally, all these admirable qualities that make them such magnificent soldiers had evaporated. This was not their kind of soldiering. It provided no opportunities for them to get to close grips with the enemy: for hour upon hour they were targets for mortars, shells and the banshee screams of the nebelwerfers. In retrospect, I wonder if we could have held on for another 24 hours, but fortunately our ordeal was nearly over.

During the morning of 22 March, the shelling of our positions became more intense and accurate. It was an inferno all day but early in the evening came the news that saved the lives of the survivors - and our sanity. Later that night we were to move back to rejoin our own battalion which had been resting while we were being hammered.

For five hectic days and nights we had been on detachment away from the 7th Gurkhas. My chief recollection was the noise that never stopped. It was to be two days before we recovered our spirits. Fortunately our colonel decided to send us back to act as reserve company again, while the other three rifle companies held the front line near the Snakeshead Ridge.

Unbeknown to us, however, the generals above had realized that 4th Indian Division was exhausted and would have to be withdrawn. We had shot our bolt and had little to show for our efforts. Our friends of the l/9th Gurkha Rifles, still clinging to the isolated position on Hangman’s Hill, were ordered to begin their withdrawal after dark on 25 March. By a miracle they made their way down the hillside and through German outposts without any major incident. Eight officers and 170 Gurkha ranks abandoned Hangman’s Hill without relief: later the Germans claimed to have counted 185 dead Gurkhas in and around their old position, the price that battalion paid for the nine days spent under the walls of the monastery.

And our turn was soon to come. In the early evening of 25 March, an advance party from the Lancashire Fusiliers arrived to begin the take-over of our positions. For me the relief could not have been delayed because by that time I was suffering from a nasty bout of

Diarrhea. In my diary I wrote: ‘Now very weak - how long can I continue?’ Next morning brought confirmation that we were to be relieved by 78th British Division during that night, a complicated and dangerous operation of war because the German outposts were, in some places, less than 100 yards from olirs. And then we faced a long march back across the valley of the Rapido to our waiting transport.

The distance was probably less than five miles, but during the time in the front line many men had hardly walked at all for six weeks. We had been cramped in foxholes, we were unfit, mentally exhausted, and many of our soldiers had lost their willpower. Even though the ordeal was nearly over, the fact did not seem to be understood. The Germans did little to hamper or harass us - indeed I believe they were relieving their own units but this was not known at the time. All we knew was that our group of dejected, tired soldiers, had to be across the valley before the sun rose the next morning. No one looked back. They just stared ahead with eyes that seemed to see nothing and kept on following the man in front, trying to force one foot past the other.

Never will I forget that nightmare of a march. Officers, British and Gurkha, shouted at, scolded, cajoled and assisted men as they collapsed. At times we had no alternative but to strike soldiers who just gave up; all interest lost in everything, including any desire to live. By dint of all the measures we could think of, most of our battalion reached the waiting transport and survived to fight another day, elsewhere, in Italy.

Cassino for us was over - a few weeks later it was to be over for the Germans as well. The third battle had been a grim struggle with few prisoners being taken, by either side, with every yard contested and no quarter given. Like many others who fought at Cassino, I remember how the decencies of war were observed to an astonishing degree. There were many examples of feelings, akin to comradeship, recounted by soldiers who fought at Cassino. Many wounded men survived because stretcher bearers were allowed to carry out their missions of mercy under the Red Cross flag in the forward areas: the contestants had a mutual respect and understanding of each other’s problems. The German High Command’s cautious claim to a victory was a true assessment because their defenders had won the battle: it was a victory, however, dearly bought because their losses were as distressingly high as ours.

When we left Cassino, the monastery still glowered down at us, an impregnable fortress. The ruins did not fall to any direct assault or succumb to the heaviest weapons available to the Allies. Monte Cassino continued to dominate the lives of the soldiers that fought under its shadow.

World History

World History