Ottoman Campaigns in the Caucasus and the Sinai

In the opening weeks of the war, the Ottomans had suffered a string of minor defeats around the fringes of their vast empire. Yet their army remained fully intact, and the Turks had yet to play the wild card of jihad against the Allies. In fact, many in the German high command believed that the Ottomans’ greatest contribution to their war effort would come less from the Turkish army than from the internal uprisings Ottoman military action might provoke among Muslims under French colonial rule in North Africa, under the British in Egypt and India, and under the Russians in the Caucasus and Central Asia. At the very least, the threat of such internal rebellions might force the Entente Powers to deploy troops in Asia and Africa to preserve the peace in their Muslim territories, relieving the pressure on the Germans on the western front and the Germans and Austrians on the eastern front.

Since mid-September 1914, this pressure had grown severe. The concerted French and British counteroffensive on the Marne (5—12 September) had brought the German war of movement to a halt and resulted in trench warfare. Stalemate in western Europe left Germany fighting a two-front war, when German war plans had called for a quick victory in France to free the German army to relieve Austria and throw its full weight against Russia. The Austrians needed all the assistance they could get on the eastern front. In August and September 1914, Austria-Hungary suffered critical defeats to the

Serbs in the Balkans and to the Russians in the eastern Austro-Hungarian territory of Galicia. Austrian losses in Galicia alone reached 350,000 men. As Austria faltered, German war planners began to pressure their Ottoman ally to initiate hostilities against Britain and Russia.1

The Germans pressed their Ottoman allies to engage the Russians and British in places that would most assist the German and Austrian war effort. General Liman von Sanders, commander of the German military mission to Turkey, suggested sending five Ottoman army corps (approximately 150,000 men) across the Black Sea to Odessa to relieve Austrian positions in Galicia and press Russian forces between the Austrians and the Turks. Berlin favoured an expedition against British positions along the Suez Canal, both to cut imperial maritime communications and to exploit Egyptian hostility to the British occupation. The kaiser and his military chiefs hoped that by striking such bold blows against the Entente, the Ottomans might inspire Muslims across Asia and Africa to take up the sultan-caliph’s call for jihad.2

The Young Turks had their own agenda and hoped to use the war to recover lost territory in both Egypt and eastern Anatolia. British-held Egypt and the “three provinces” (Elviye-i Selase) taken by the Russians in 1878 were Ottoman Muslim lands. The Young Turks were confident their soldiers would fight to recover Ottoman territory and hoped their successes would encourage local Muslims to rise up against the Russians and British.3

In mid-November 1914, Enver Pasha, Ottoman minister of war, invited his colleague Cemal, the minister of marine, home for a private meeting. “I want to start an offensive against the Suez Canal to keep the English tied up in Egypt,” Enver explained, “and thus not only compel them to leave there a large number of Indian divisions which they are now sending to the Western Front, but prevent them from concentrating a force to land at the Dardanelles.” Towards this end, the minister of war offered Cemal the commission to raise an army in Syria to lead the attack on British positions in the Sinai. Cemal accepted the commission with alacrity and promised to set off within the week.4

On 21 November, Cemal boarded a train at Istanbul’s Haidar Pasha Railway Station to begin his journey to Syria. The station was crowded with members of the cabinet, leading Ottoman statesmen, and the diplomatic corps, in the caustic words of US Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, “to give this departing satrap an enthusiastic farewell”. Carried away by their war enthusiasm, the patriotic crowd hailed Cemal prematurely as the “saviour of Egypt”. Just before the train pulled away, Cemal pledged to his supporters that he would not return “until I have conquered Egypt”. Mor-genthau, no fan of the Young Turks, found “the whole performance. . . somewhat bombastic”.5

Enver Pasha took it on himself to lead the attack on Russia. He had no interest in German plans for an operation on the north shore of the Black Sea, far removed from Ottoman frontiers. He focused instead on the lost “three provinces” of eastern Anatolia. Enver believed that a sizeable Muslim population in the Caucasus would respond enthusiastically to an Ottoman offensive. Moreover, Enver believed Turkish forces had taken the measure of the Russian Caucasus Army. The Russians had already initiated hostilities against the Turks on the Caucasus frontier. The Ottomans’ recent success in turning back the Russian advance at Koprukoy had stirred Enver’s ambitions. On 6 December, Enver called on Liman von Sanders to announce he was sailing that night for the Black Sea port of Trabzon to lead an attack on the Caucasus frontier. As Liman later recalled, “Map in hand Enver sketched to me the outline of the intended operations by the Third Army. With one army corps, the Eleventh, he meant to hold the Russians in front on the main road, while two corps, the Ninth and Tenth, marching by their left were to cross the mountains by several marches and then fall on the Russian flank and rear in the vicinity of Sarikamisch. Later the Third Army was to take Kars.” The plan Enver outlined was fraught with risks. The mountainous terrain and inadequate roads compromised troop movements, supply lines, and lines of communication. When Liman raised his concerns, Enver insisted that these issues “had already been considered and that all roads had been reconnoitered”.6

Bringing his meeting with Liman to a close, Enver played to Berlin’s deepest hopes for the Ottoman jihad. As the German general recorded, Enver “gave utterance to phantastic, yet noteworthy ideas. He told me that he contemplated marching through Afghanistan to India. Then he went away.” Liman did not rate Enver’s chances of success very highly, but he wasn’t going to get in his way.

Two of the ruling Young Turk triumvirs set off to lead the first Ottoman ground campaigns against the Entente Powers. Perhaps, had they focused

Their efforts on a single campaign, they might have stood a chance of success. The rush to take on two Great Powers with inadequate preparation condemned both campaigns to catastrophic failure.

Enver Pasha sailed the Black Sea from Istanbul to Trabzon, where he disembarked on 8 December. Accompanied by two of his closest German advisers, Colonel Paul Bronsart von Schellendorf and Major Otto von Feldmann, he made his way overland to the headquarters of the Ottoman Third Army in the garrison town of Erzurum. Many in the Ottoman high command complained that the Germans had too much influence over their minister of war. Indeed, the broad outlines of Enver’s bold plan to defeat the Russian Caucasus Army can be traced back to his German advisers.

In late August 1914, German forces performed a perfect flanking operation against the Russians in Tannenberg, East Prussia. While the Germans engaged Russian troops along the front line, they dispatched infantry and artillery by road and rail around the Russians’ left flank, cutting their supply and communications lines and encircling the tsar’s troops. By the time the Russians realized the danger they were in, it was already too late. The Germans destroyed the Russian Second Army, inflicting 30,000 casualties and taking 92,000 men prisoner in what would prove the most complete German victory of the First World War. Enver hoped to adapt German tactics to lead the Ottoman army to a similar triumph against Russian forces in the Caucasus.7

Enver, an impetuous man, had made his career through bold, high-risk initiatives. A historic leader of the 1908 revolution, an architect of the 1911 Ottoman-led jihad in Libya, leader of the 1913 raid on the Sublime Porte who forced the prime minister to resign at gunpoint, and “liberator of Edirne” in the Second Balkan War, Enver believed in taking action and had little doubt in his own judgment and abilities. He clearly believed he could lead an army to victory against Russia and that such a victory would be of the greatest benefit to the Ottoman war effort. The Turks would not only regain territory lost to Russia in 1878 but could discourage further Russian ambitions in Ottoman territory—particularly in the straits and Istanbul. And, as Enver suggested to Liman von Sanders, a glorious battlefield victory might just trigger Islamic enthusiasms in Central Asia that would open the road to Afghanistan and India.

Ottoman commanders in the field had their doubts that the battle plan developed in Tannenberg at the height of summer could be applied to the very different setting of the Caucasus Mountains in winter. The Germans, operating very close to well-stocked bases, had relied on roads and railways to move large numbers of troops into position to complete the encirclement of Russian forces at Tannenberg. The unpaved roads and footpaths in the mountainous highlands of eastern Anatolia were practically impassable to wheeled traffic in winter. With mountain peaks in excess of 3,000 metres, winter snows 1.5 metres in depth, and temperatures plunging to -20°C, only soldiers with special training and equipment could survive, let alone prosecute a successful war, in such hostile conditions. Yet even the most sceptical Ottoman officers believed Enver was lucky and just might be able to secure a victory against all the odds.8

In the course of the summer of 1914, Enver had consolidated Ottoman forces in the Caucasus region of eastern Anatolia into the Third Army, headquartered in Erzurum. In September, the XI Corps was redeployed from its base in Van to join the IX Corps in Erzurum, and in October the X Corps was transferred secretly from Erzincan to bring the Third Army to fighting trim. By the time Enver reached Erzurum in December 1914, the total strength of the Third Army was around 150,000 men (including Kurdish irregular cavalry and other auxiliaries). That gave the Turks a campaign force of some 100,000 to use against the Russians, while holding the remainder in reserve to secure Erzurum and the Caucasus frontier from Lake Van to the Black Sea—nearly three hundred miles in all.9

The commander of the Ottoman Third Army, Hasan Izzet Pasha, had reviewed Enver’s battle plan and given his qualified support for the attack on Russian positions. He argued that his men needed proper provisions for a winter campaign, including cold-weather clothing, sufficient food, and stores of ammunition. To Enver, such sound logistical considerations were but delaying tactics on the part of an overly cautious commander. He placed his trust instead in an ambitions officer named Hafiz Hakki Bey, who wrote Enver in secret to claim he had reconnoitred the roads and passes and was convinced they could be used in winter by infantry with mountain guns (light artillery that could be transported by mules). “The commanders here do not support the idea [of a winter campaign] because they lack persistence and courage,” he wrote to Enver. “Yet I would undertake this task if my rank were adjusted accordingly.”10

When Enver arrived to launch the campaign, Hasan Izzet Pasha tendered his resignation as commander of the Third Army. He simply did not believe the campaign could succeed without adequate provisions for the soldiers. Given his knowledge of the surrounding area, Hasan Izzet Pasha was a loss to the Ottoman war effort in the Caucasus. Yet Enver had lost confidence in the general and, in accepting his resignation, took personal command of the Third Army on 19 December. He also promoted the ambitious Hafiz Hakki Bey and put him at the head of the X Corps. Commanding officers with little or no experience of formal military campaigns and very limited knowledge of the dangerous terrain were now in charge, as Enver issued orders for the fateful attack on the Russian railhead at Sarikamij, to begin on 22 December.

As Enver’s campaign came to eastern Anatolia, the Armenians found themselves on the front line, their loyalties divided between the Russian and Ottoman empires. In 1878, a sizable Armenian population in the three provinces of Kars, Ardahan, and Batum had passed from Ottoman to Russian rule. While the tsarist government had proven no more accommodating of Armenian separatist aspirations than the Turks, St Petersburg played on a common Christian identity (notwithstanding the deep doctrinal divides between Russian and Armenian Orthodoxy) in a bid to turn the Armenians against the Muslim Turks.

Russian and Turkish religious politics in the Caucasus had a certain symmetry, with the tsarist government hoping to foment a Christian uprising against the Turks, just as the Ottomans sought to exploit Muslim solidarity to provoke jihad among Caucasian Muslims against Russia. In the Russian Caucasus, the Armenian National Council had worked closely with the tsarist government even before the outbreak of war to recruit four volunteer regiments to assist a Russian invasion of Turkish territory. Russian consular officials and military intelligence concurred that such Armenian volunteer units would encourage Ottoman Christians to assist a Russian invasion, and in September 1914 Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, signed orders to smuggle Russian arms to Ottoman Armenians ahead of Turkey’s anticipated entry into the war. A number of prominent Ottoman Armenians crossed the frontier to join the Russian war effort, though most held back, fearing their involvement in such regiments would jeopardize the safety of Armenian civilians under Ottoman rule.11

In the summer months of 1914, Ottoman officials kept a watchful eye on the Armenians of eastern Anatolia. In July and August, while Ottoman war mobilization was at its height, the Armenian men of Van, Trabzon, and Erzurum reported for duty while the civilian population remained, by all accounts, loyal. Yet the Russians reported over 50,000 deserters from the Ottoman army, most of them Armenians, crossing over to Russian lines between August and October 1914.12

Amid mounting concern over Armenian loyalties, the Young Turks convened a meeting in Erzurum in October, at which they proposed an alliance with the Armenian nationalist parties, the Dashnaks and Hun-chaks. The Ottomans pledged to establish an autonomous Armenian administration comprising several provinces in eastern Anatolia and any territory conquered from Russian Armenia in return for assistance against the Russians from Armenian communities in both Russia and Turkey. The Armenian nationalists declined, arguing that Armenians should remain loyal to the governments under which they lived on both sides of the Rus-sian-Ottoman border. This reasonable response only fed Ottoman doubts about Armenian loyalties.13

Relations between Armenians and Turks deteriorated rapidly after the outbreak of the war. Corporal Ali Riza Eti, who had served in a medical unit during the Battle of Koprukoy, grew increasingly hostile to the Armenians he encountered at the front. Towards the end of November, the Russians deployed their Armenian volunteer units in eastern Anatolia. They engaged Ottoman forces from Van, a major centre of the Ottoman Armenian community, along the Aras River—no doubt with the deliberate intention of encouraging Armenians to defect from Ottoman ranks. Many did: Corporal Eti claimed that Armenians in groups of forty or fifty deserted to join with Russian forces. “Obviously they will inform the enemy of our positions,” Eti reflected.14

In November, Eti’s unit marched through a number of deserted villages whose Armenian residents had gone over to the Russians and whose Muslim inhabitants had fled or been killed by the invaders. “When the Armenians of this area sided with the Russian Army,” he wrote in his diary on 15 November, “they showed great cruelty to those poor villagers.” He described desecrated mosques littered with animal carcasses and the pages of broken

Qurans carried by the wind down empty streets. The anger in his writing is palpable.15

As word of Armenian defections gained circulation, Turkish soldiers grew increasingly violent towards the Armenians in their midst. Eti mentioned casually how a Turkish soldier’s weapon “discharged” and struck down an Armenian comrade. From Eti’s account, it hardly sounded like an accident. “We buried the guy,” he wrote dispassionately. There was no suggestion of disciplinary action for the killing of a fellow Ottoman soldier. Increasingly, Armenians were no longer seen as fellow Ottomans.16

In the days leading up to the Turkish offensive, Enver Pasha made the rounds to review his troops. The Third Army commander’s message to Ottoman soldiers was sobering. “Soldiers, I have visited you all,” he declared. “I saw that you have neither shoes on your feet nor coats on your backs. Yet the enemy before you is afraid of you. Soon we will attack and enter the Caucasus. There you will find everything in abundance. The whole of the Muslim world is watching you.”17

Enver’s optimism for his army’s chances of success stemmed from a series of favourable developments on the Caucasus front. With winter fast approaching, the Russians did not believe the Ottomans would attempt hostilities before spring. They took the opportunity to redeploy surplus troops from the Caucasus to more pressing fronts, reducing the size of the army in eastern Anatolia. The Turks, on the other hand, had managed to transfer the X Corps without the Russians’ knowledge. These troop movements gave the Ottomans a numerical advantage over the Russians, with some 100,000 Turkish troops facing fewer than 80,000 Russians.18

With the Russians bedding down for the winter, Enver hoped a surprise attack would catch the enemy with his guard down. To preserve the element of surprise, Ottoman forces needed to move quickly into Russian territory. Enver ordered his men to leave their heavy packs behind and to carry only their weapons and ammunition with a minimum of provisions. While lightening his soldiers’ load, Enver’s order also meant his troops carried no fuel, tents, or bedding and only half rations. Enver hoped to billet and feed his men off the Russian villages they would conquer on their way to Sarikamij. “Our supply base is in front of us,” was Enver’s mantra.19

Most Russian forces were dispersed inside Ottoman territory, along the salient they had seized in the fighting in November. Their supply centre at Sarikamij was practically undefended, with only a handful of frontier guards, militiamen, and railway workers to protect their sole line of supply and communications, as well as their only line of retreat through the mountain valleys back to Kars.

This was Enver’s dream: to send a large force around the Russian right flank both to cut off the railway line and to seize the town of Sarikamij, surrounding the Russian Caucasus Army, which, severed from its only line of retreat, would have no choice but to surrender to the Turks. Once Sarikamij was secured and the Russian Caucasus Army destroyed, the Ottomans could retake Kars, Ardahan, and Batum—the three provinces lost in 1878—unopposed. Such brilliant Ottoman victories would stir the Muslim populations of Central Asia, Afghanistan, and India beyond. The conquest of one strategic railhead opened such remarkable possibilities for both the Ottoman Empire and the ambitious Young Turk generalissimo.

In his battle plan, issued on 19 December, Enver assigned distinct objectives to each of the three corps (each comprising 30,000 to 35,000 soldiers) of the Third Army. The XI Corps was ordered to engage Russian forces along the length of its southern front as a diversion to provide cover for the IX and X corps while they manoeuvred around to the west and north towards Sarikamij. The IX Corps was to follow an inner loop and descend on Sarikamij from the west, while the X Corps took the outer loop, sending one division (roughly 10,000 men) north towards Ardahan and two divisions to cut the railway line and descend on Sarikamij from the north. Operations were scheduled to begin on 22 December.20

After a period of unseasonably fair weather, the winter snows began to fall on the night of 19—20 December. A major snowstorm struck on the morning of 22 December, as the Ottoman Third Army went into action. Carrying only flat bread for rations, dressed in light uniforms without proper coats to protect them against the cold, and shod with inadequate footwear for the harsh terrain, the Ottoman soldiers set off under the most adverse conditions to fulfil the superhuman tasks Enver had set them.

Ottoman forces of the XI Corps opened hostilities along the south bank of the Aras River to divert Russian forces from the west of Sarikamij, where the Ottoman IX and X corps planned to outflank Russian positions.

Corporal Ali Riza Eti watched from the medics’ tents as the Russians returned fire, inflicting heavy casualties and driving the Turks into retreat. As the Ottomans fell back, Eti grew concerned that the advancing Russians would capture his medical unit.

Eti heard many stories of near escapes from the Russians told by incoming wounded. When one Turkish-held village fell to the Russians, a group of sixty Ottoman soldiers took refuge in a hayloft. They were discovered by three Russian Muslim soldiers of a Kazak regiment who, after making the Turks prove they were Muslim by showing their circumcised penises, left them in hiding. “Brothers, be quiet and wait here,” the Kazaks explained, “we are leaving now.” Such fraternization between Muslim soldiers across battle lines met with Eti’s full approval.21

Christian fellow feeling between Armenians and Russians, however, continued to infuriate Medical Corporal Eti. On the first day of battle, he saw two Ottoman Armenian soldiers cross over to Russian lines and a third shot and killed in the attempt. Turkish soldiers blamed the Armenians not just for defecting but for providing the Russians with intelligence on Ottoman positions and numbers. “Isn’t it natural that the Russians would gain information from the Armenians who flee from the army every day?” he reflected bitterly. “I wonder if anything will be done to the Armenians after the war?”22

Armenian soldiers in Ottoman ranks faced an intolerable situation. They were actively recruited by Armenians in Russian ranks and knew their lives were in danger the longer they stayed among Ottoman soldiers whose mistrust was growing murderous. Eti reported that in every battalion between three and five Armenians were shot daily “by accident” and mused, “If it goes on like that, there won’t be any Armenians left in the battalions in a week.”23

The XI Corps faced heavy resistance from Russian troops. The front line was too long for the Turks to mount more than a modest assault at any given point, and in the first days of the attack, they not only failed in their efforts to force the Russians north of the Aras River but were driven back towards their own headquarters in Koprukoy. Though their casualties mounted, the XI Corps succeeded in drawing the fire of Russian troops, providing the necessary diversion for the IX and X corps to execute their flanking operation. In the opening days of the campaign, these two Ottoman army corps achieved remarkable successes.

The Ottoman X Corps, commanded by Hafiz Hakki Bey, raced northward to capture territory from the Russian right flank. They cut through the Russian salient and proceeded northward across the frontier to lay siege to the lightly defended garrison town of Oltu. The Ottomans surprised a Russian colonel along the way, who surrendered with the 750 soldiers under his command. Yet the Ottomans faced some nasty surprises of their own. Caught in heavy fog outside Oltu, one Turkish regiment mistook another for Russian defenders and battled for four hours against its own troops, incurring over 1,000 Ottoman casualties through friendly fire. However, by the end of the day, the Ottomans had succeeded in driving the Russian defenders out of Oltu. Here at least, the Ottoman soldiers found food and shelter as promised, and they set about looting the conquered town.24

True to form, the headstrong Hafiz Hakki followed his victory in Oltu by pursuing the retreating Russians with all of his forces rather than making his way eastward to join up with Enver Pasha and the IX Corps in their attack on Sarikamij. Given the difficulties of communications in the mountainous terrain, this spontaneous change of plan placed the whole campaign in jeopardy.

Enver Pasha accompanied the IX Corps on its treacherous course towards Sarikamij. The determined Ottoman soldiers made their way through narrow mountain paths obstructed by snowdrifts, covering forty-six miles in just three days. The cold took its toll, as the men were forced to sleep in the open, without tents and only the scrub they could scavenge for firewood in subfreezing temperatures. In the morning light, groups of men could be found lying in circles around the remains of fires that proved no match for the cold, their corpses blackened by the ice. Over one-third of the men of IX Corps never reached the Sarikamij region.

Yet Enver drove his men onward to the outskirts of Sarikamij, where they paused on 24 December to consolidate before the final attack on the garrison town. The Turks, interrogating their Russian prisoners, learned there were no troops to defend Sarikamij at all except for a few rear units without artillery. Realization of how weakly the strategic town was fortified reaffirmed Enver’s conviction that his frozen and exhausted troops were within striking distance of total victory.25

The Russians only learned the full extent of the Turkish assault on 26 December, when they captured an Ottoman officer and secured copies of Enver’s war plans. They now knew that the X Corps had been redeployed to the Third Army and that the Ottomans enjoyed a sizable numerical advantage. They had learned of the fall of Oltu and that Ottoman troops were not only advancing on Ardahan but due to arrive shortly in Sarikamij. The Muslim population between the Black Sea port of Batum and Ardahan had risen in revolt against the Russians—precisely the religious enthusiasm the Ottomans hoped to provoke and the Russians most feared. The Russian generals were, according to historians of the campaign, “almost in a state of panic. . . convinced that Sarikamij would be lost and that the bulk of the Caucasian army would be cut off from their line of retreat to Kars”. The Russian commanders ordered a general retreat in a desperate bid to save their army, or at least some part of it, from total defeat.26

Fortune favoured the Russians, as the Turkish battle plan began to unravel. After a remarkable start, the weather and human error began to take their toll on the Ottoman expedition. Blizzards swept the high peaks of the Caucasus, making the mountain paths all but impassable to those on the march. In zero visibility, with windswept snow hiding the mountain tracks, many men got separated from their units, thinning the ranks. The lack of proper roads, the extreme weather, and the high mountains played havoc with Ottoman communications. Worse yet, one of Enver’s generals, Hafiz Hakki Bey, had disregarded his orders and was pursuing a small Russian force that led him miles away from Sarikamij.

Enver dispatched urgent orders to Hafiz Hakki Bey to break off his pursuit of Russian forces and fall back into line with the original battle plan. The commander of X Corps entrusted the assault on Ardahan to one of his regiments (as set out in the original battle plan) and personally led the two other regiments of X Corps to join in Enver’s assault on Sarikamij. Hafiz Hakki set off on 25 December and promised to meet Enver the following morning. He was at that point thirty miles away from the Sarikamij front and had to cross the high massif of the Allahuekber Mountains, rising 3,000 metres above sea level, in the full fury of winter. The next nineteen hours were nothing short of a death march. One of its survivors described the hardships the soldiers suffered: “We climbed with great difficulty, yet were orderly and disciplined. We were very tired and exhausted. When we reached the plateau, we were hit by a strong blizzard. We lost all visibility. It was impossible to help let alone talk to each other. The troops lost all order. Soldiers ran anywhere to seek shelter, attacking any house with smoke coming from its chimney. The officers worked very hard, but they could not force the soldiers to obey.” The cold was beyond human endurance, driving some of the soldiers mad: “I still remember very clearly seeing a soldier sitting in the snow by the side of the road. He was embracing the snow, grabbing handfuls and stuffing it into his mouth as he trembled and screamed. I wanted to help him and lead him back to the road, but he kept shouting and piling up the snow as if he did not see me. The poor man had gone insane. In this way we left 10,000 men behind under the snow in just one day.”27

On 25 December, Enver Pasha convened a meeting of his Turkish officers and German advisors to take stock of the situation. The Russians had begun to retreat from their front line along the Aras River to fall back on Sarikamij. Reinforcements were being sent down the railway line to offer assistance to the retreating Russians, who still believed their cause was lost. While their commanders were still in disarray, this meant that large numbers of Russian soldiers were descending on Sarikamij from the north and the south. If the Ottomans did not act soon, they might lose the chance to take the town while it was still relatively undefended.

In the meeting, IX Corps commander Ihsan Pasha and §erif Ilden, the chief of staff, were given a grilling by Enver and his German advisors. When, they wanted to know, would the Ottoman expedition be in a position to take Sarikamij? Ihsan Pasha presented his commanders with the hard truths of the Third Army’s position. They had lost all contact with Hafiz Hakki and the X Corps, who were at that point marching over the Allahuekber Mountains, and could not say with any confidence when they would be in position to join an attack on Sarikamij. Only one IX Corps division was currently available within striking distance of the town. “I don’t know what the requirements of the campaign are,” Ihsan Pasha concluded. “If your orders could be carried out with one division, then the 29th Division is ready for your orders.”28

After hearing from his Turkish officers, Enver asked his German advisers for their opinions. They shared full responsibility with Enver in drafting the original battle plan and had fed his ambition to replicate the German victory in Tannenberg on the Caucasus front. They advised Enver to wait until Hafiz Hakki arrived with his troops before attacking. Yet Enver was not for waiting. He knew that the longer he delayed, the more Russian troops his own soldiers would face. Moreover, once his soldiers had taken Sarikamij, they would have roofs over their heads and food to eat. Each night his army spent in the open left hundreds more soldiers dead from exposure. His officers believed Enver was driven to action by an unspoken rivalry with Hafiz Hakki, fearing that the X Corps commander might reach and occupy Sarikamij before him. Enver, always at the front, cherished that particular trophy for his own glory.

In the end, Enver Pasha overrode all his advisers and ordered his troops to begin their attack the next morning, 26 December. This fateful decision proved the turning point in the Ottoman campaign. From that moment forward, every Ottoman attack lacked the manpower to prevail or to retain any ground won against Russian counter-attacks.

It is to the credit of the tenacity of the Ottoman soldiers that each of the objectives of Enver’s unrealistic plan was achieved—however briefly. Hafiz Hakki’s men, after crossing the forbidding Allahuekber Mountains, reached the railway between Kars and Sarikamij and cut that vital line of communica-tion—though with insufficient men to hold it against Russian reinforcements from Kars. Ottoman troops captured the town of Ardahan but, with insufficient forces to hold the city, lost it within a week. The once victorious Turkish soldiers of the X Corps found themselves surrounded, and the 1,200 survivors of the original force of 5,000 were forced to surrender to the Russians. Ottoman troops even managed to penetrate into Sarikamij itself, though the price they paid in lives lost overshadowed that short-lived accomplishment.

The IX Corps’s first attacks on Russian positions in Sarikamij were repelled with heavy losses by the town’s defenders on 26 December. That night, Hafiz Hakki Pasha and the exhausted survivors of the march over the Allahuekber Mountains finally reached their positions near Sarikamij. Given the losses the IX Corps had suffered and the deplorable state of the X Corps after its forced march, Enver decided to suspend operations for thirty-six hours to consolidate his forces.29

The decisive battle for Sarikamij was fought on 29 December. By that time, the cold had decimated Ottoman numbers. From an original strength of more than 50,000 men, the Ottoman IX and X corps together numbered no more than 18,000, and those survivors were in no condition to fight. Russian numbers in Sarikamij had risen to over 13,000 defenders in the town, with more artillery and machine guns than the Turks had, in well-defended positions. With these heavy weapons, the Russians succeeded in repelling determined Turkish attacks throughout the day.

Enver made one last attempt to take Sarikamij with a night attack on 29 December. This time, his forces swept into the garrison town, engaging

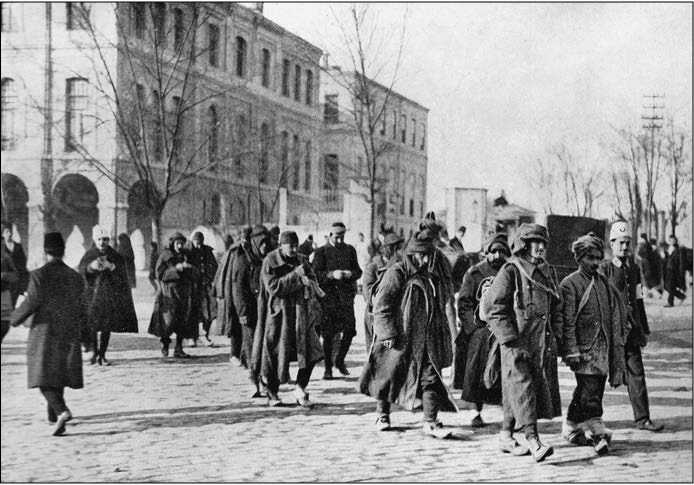

Ottoman prisoners in Ardahan. One detachment of the Ottoman Caucasus Army succeeded in capturing the town of Ardahan from Russian forces during the Sarikami§ campaign but, with insufficient forces to hold the city, was forced to surrender in early January 1915 in what was touted as the first Russian victory on the Caucasus front.

The Russian defenders in hand-to-hand combat with bayonets in the dark. Most of the Turkish soldiers were killed or taken prisoner, though a determined squad of several hundred men succeeded in occupying the Russian barracks in the centre of the town. For one night, a small part of Enver’s army could claim to have occupied a small part of Sarxkamij. By morning, Russian forces surrounded the barracks and forced the Turkish soldiers to surrender. An entire Ottoman division was lost in the offensive.

The Russians soon realized how weak the Ottoman attackers were and, recovering from their initial loss of composure, went on the offensive. Now the Ottoman Third Army, rather than the Russian Caucasus Army, was in imminent danger of encirclement and destruction.

In the first two weeks of January 1915, Russian forces drove the Ottomans back, recovering all of the territory they had surrendered in the opening days of the campaign. In the process, they destroyed the Third Army, corps by corps. The IX Corps was surrounded by the Russians and forced to surrender on 4 January. The chief of staff, §erif Ilden, recorded that there were only 106 officers and eighty soldiers with him at the IX Corps’ headquarters when he surrendered to the Russians. Hafiz Hakki led the X Corps into a retreat under fire but managed to avoid total destruction, and after sixteen days, some 3,000 survivors reached the security of Turkish lines.30

As the IX and X corps collapsed, the XI Corps took the brunt of the Russian counter-attack. At one point during their retreat from Russian territory, Turkish troops were surprised when an alien cavalry force charged the Russian left flank and scattered the enemy. They were a group of Circassian villagers who, learning of the sultan’s declaration of jihad, immediately rode out to support the Ottoman troops. It was, for Medical Corporal Ali Riza Eti, who witnessed the Circassian attack, further proof of Muslim solidarity in the Great War. The XI Corps completed its retreat to Turkish lines by mid-January, with 15,000 of the original complement of 35,000 soldiers. But the Ottoman Third Army had been destroyed. Of the nearly 100,000 soldiers sent to battle, only 18,000 broken men returned.31

Enver Pasha narrowly managed to escape capture and returned to Istanbul in disgrace, though neither Enver nor Hafiz Hakki faced any disciplinary hearing for what some of their officers condemned as criminal neglect. In fact, before leaving Erzurum for the imperial capital, Enver promoted the rash Hafiz Hakki from colonel to major general, with the title of pasha, and placed him in command of what remained of the Third Army (he died two months later of typhus). The defeat was too terrible for the Young Turks to acknowledge, and according to Liman von Sanders, the destruction of the Third Army was kept secret in both Germany and the Ottoman Empire. “It was forbidden to speak of it,” he later wrote. “Violations of the order were followed by arrest and punishment.”32

The repercussions of Sarikamij would be felt for the remainder of the war. Without an effective army in eastern Anatolia, the Ottomans were unable to defend their territory from Russian attack. Ottoman vulnerability heightened tensions between Turks, Kurds, and Armenians in the frontier zone with Russia. And whatever enthusiasm for jihad Muslims in the Russian Empire might have shown in the early stages of the Sarikamij campaign, the totality of Ottoman defeat ruled out the prospect of an Islamic uprising on the Russian front.

The magnitude of the Ottoman defeat served to encourage Russia’s Entente allies in their plans for an attack on the Dardanelles to seize Istanbul and take the Turks out of the war once and for all.33

One month after the Ottoman defeat at Sarikami§, Cemal Pasha led an attack on the British in the Suez Canal. The contrast between the deserts of Egypt and the blizzards of the Caucasus could not have been more extreme, though the arid wastelands of Sinai were no more hospitable to a campaign force than the high mountains around Sarikamij.

After his very public proclamations in Istanbul’s central train station on 21 November 1914, no one could accuse Cemal of hiding his intention to lead an expedition against Egypt. Given the obstacles any such expedition would encounter, the British dismissed Cemal’s pledge to “conquer” Egypt as empty rhetoric. They did not think Cemal could raise an army in Syria large enough to threaten British forces in Egypt. Even if he did succeed in putting together a large campaign force, no proper roads crossed the Sinai, which had few sources of water and almost no vegetation. The logistics of providing food, water, and ammunition for a large campaign force crossing such inhospitable terrain were forbidding. And even if they were to overcome all of those obstacles and reach the canal, Ottoman forces would still face a body of water hundreds of metres wide and twelve metres deep protected by warships, armoured trains, and 50,000 troops. The British position looked unassailable.

British calculations were not wrong. Cemal faced serious constraints in mobilizing a campaign force in Syria. In December 1914, the Ottomans needed all their soldiers in Anatolia to reinforce the ill-fated Caucasus frontier and to protect Istanbul and the straits. Cemal would be reliant on the regular soldiers of the Arab provinces, reinforced by irregular volunteers from local Bedouin, Druze, Circassian and other immigrant communities. Of the 50,000 combatants at his disposal, Cemal would be able to deploy no more than 30,000 for the Suez campaign, as the rest would be needed to man garrisons across the Arab provinces. Moreover, the Ottoman commander would have to retain 5,000 to 10,000 soldiers in reserve, to protect or reinforce the initial campaign force. This meant Cemal would have only 20,000 to 25,000 Ottoman soldiers with which to take on a dug-in British force at least twice that size—a suicidal proposition.34

To succeed, Cemal counted on a sequence of improbable events. “I had staked everything upon surprising the English,” Cemal later recorded. If caught by surprise, he hoped the English might surrender a stretch of the Canal Zone that the Ottomans could reinforce with “twelve thousand rifles securely dug in on the far bank”. From such a bridgehead, Cemal planned to occupy the key town of Ismailia, raising Ottoman numbers on the west bank of the canal to 20,000. And the Ottoman occupation of Ismailia, he believed, would inspire a popular uprising in Egypt against British rule—the jihad that the sultan had called for. In this way, Cemal argued, “Egypt would be freed in an unexpectedly short time by the employment of quite a small force and insignificant technical resources.”35

Cemal’s rash plan had the full support of the Germans, who still harboured high hopes for the Ottoman-led jihad. Moreover, Germany placed a high priority on cutting the Suez Canal. Between 1 August and 31 December 1914, no fewer than 376 transport ships transited the canal, carrying 163,700 troops for the Allied war effort. While the British were not totally reliant on the canal for troop transport—the rail system linking Suez to Cairo and the Mediterranean ports could have served this purpose—it was a vital artery for war and merchant ships traveling from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean. So long as the canal was operating, Britain could derive full benefit from its empire for the war effort. Any Ottoman attack on Suez that slowed this imperial traffic or forced Britain to concentrate troops for the defence of Egypt that might otherwise be deployed to the western front was of direct benefit to the German war effort.36

From the moment Cemal reached Damascus on 6 December, he set to work mobilizing the men and resources to undertake the perilous crossing of the Sinai. His regular forces numbered some 35,000 soldiers, primarily young men from the Arab provinces of Aleppo, Beirut, and Damascus and the autonomous districts of Mount Lebanon and Jerusalem. To bolster his numbers, Cemal appealed to the patriotism of tribal leaders across the Arab lands to join the attack on the British and liberate Egypt from foreign rule.

Druze prince Amir Shakib Arslan was a serving member of the Ottoman parliament in 1914. When he learned of Cemal’s plans, Arslan applied to Istanbul for release from his parliamentary duties to lead a detachment of Druze volunteers for the Sinai campaign. He met with Cemal and promised to raise five hundred men for the war effort, though the Young Turk leader asked for no more than one hundred. Arslan came away from his interview convinced Cemal “thought that disorganized volunteers would not be of great value to the war”. Yet Arslan claimed his Druze volunteers exceeded all expectations, outperforming regular soldiers in riflery and horsemanship in the Damascus military depot. Instead of the month’s training initially

Ottoman soldiers in Palestine before the first attack on the Suez Canal. Cemal Pasha assembled the main body of his expeditionary force for the assault on the Suez Canal in Syria and Palestine in January 1915. Large bodies of troops combining Ottoman regulars and tribal volunteers mustered in shows of patriotism intended to raise public support for the war effort in the Arab provinces.

Envisaged, the Druze volunteers were dispatched without delay by train to join the campaign.37

In december 1914 and January 1915, a heterogeneous army was assembling in the fortified desert frontier town of Maan (today in southern Jordan), some 290 miles south of damascus. Maan, on the pilgrimage route from damascus to Mecca, was also a major depot on the Hijaz Railway. Here Arslan found a “unit of volunteers from the people of Medina, and another unit of mixed Turks from Romania, and Syrian Bedouin and Albanians and others”, including Kurdish cavalry from the Salahiyya district of damascus.

Wahib Pasha, the governor and military commander of the Red Sea province of the Hijaz (which included Mecca and Medina, the birthplace of Islam), headed the largest force in Maan. Arslan claimed that Wahib Pasha brought 9,000 soldiers from the Ottoman garrison in Mecca, though there was a notable absence among his levies. Cemal Pasha had written Sharif Hu-sayn ibn Ali, the chief Ottoman religious authority in Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, asking him to contribute a detachment of forces under the command of one of his sons. Cemal hoped that the sharif would lend his religious authority to the Suez expedition and prove his loyalty to the state. Sharif Husayn replied courteously to Cemal’s request and sent his son Ali with Wahib Pasha when the governor set out from Mecca. However, Ali went no further than Medina, promising to catch up with Wahib Pasha as soon as he had mobilized his full volunteer force. Cemal noted with concern that Sharif Husayn’s son never left Medina.38

The main body of the Ottoman Expeditionary Force assembled in January 1915 in Beersheba (today in southern Israel), near the Ottoman-Egyptian frontier. Here Ottoman and German planners worked to prepare the logistics of the expedition. The chief of staff of the Ottoman VIII Corps, Colonel Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, positioned supply depots every fifteen or so miles between Beersheba and Ismailia, where the headquarters of the Suez Canal were based. In each depot, engineers dug wells and built dykes to trap the winter rains to provide adequate water facilities for the army. Medical facilities and food stores were prepositioned in each depot. Over 10,000 camels were requisitioned from Syria and Arabia to provide transport between depots, and provisional telegraph lines were laid to provide instant communications.

The greatest challenge facing the Ottoman expedition was the transport of twenty-five pontoons designed for crossing the Suez Canal. The pontoons, made of galvanized iron, ranged from 5.5 to 7 metres in length and 1.5 metres in width. Ottoman soldiers, aided by camels and mules, pulled these flat-bottomed boats on specially devised trailers, laying boards over the soft sand to keep the trailer wheels from getting stuck. Ottoman soldiers practiced pulling the unwieldy craft overland and making bridges with the boats.

The British seem to have had little appreciation of the campaign force taking shape in Syria. A French priest, whom the Ottomans had expelled from Jerusalem, was the first to give detailed intelligence on Cemal’s preparations. The British interviewed the priest in the Canal Zone on 30 December. The priest knew the Syrian Desert intimately from his many years of archaeological work and spoke fluent Arabic. He claimed to have seen as many as 25,000 men assembling in Damascus and Jerusalem with extensive materiel, including boats, wire, and telegraph equipment, all making their way towards Beersheba. Provision was being made for water, and biscuit cooked in Damascus was being stored in depots in Sinai. At first the British dismissed his comments as ridiculous, but the more detail he gave, the more seriously they took his report.39

The British and French began to deploy airplanes for the first time in the war in the Middle East in an attempt to secure aerial confirmation of the French priest’s report. It was the Ottomans’ good fortune that the central regions of Sinai, where the ground was firmest and best suited for marching an army, was also the furthest from reach of aerial surveillance, affording the Suez campaign a surprising degree of secrecy on the eve of its departure. British planes based in Ismailia were too short-range to penetrate into central Sinai, while French seaplanes operating from Port Said and the Gulf of Aqaba could only view the northern and southern extremities of the Sinai Peninsula, where the smaller Turkish contingents were concentrated. The Ottomans and Germans had yet to deploy aircraft to support their own troops, leaving the Allies in control of the skies.

When the first echelon of Ottoman forces set out from Beersheba towards the canal on 14 January 1915, the British had little idea of either where they were or where they were headed. The main body of Ottoman forces marched through the centre of the Sinai, while two smaller detachments diverged, one heading along the Mediterranean coast from El Arish and the other passing through the desert fort of Qalaat al-Nakhl. Each man carried light rations of dates, biscuit, and olives not to exceed one kilo in weight, and water was carefully rationed. The troops found the winter nights too cold to sleep, so they marched through the night and rested during the day. It took twelve days to cross the desert, with the loss of neither a man nor a beast along the way—a tribute to the detailed planning behind the Suez campaign.

In the last ten days of January, French seaplanes began to report alarming concentrations of Turkish troops within those areas their planes had the range to reach. The low-flying aircraft returned to base with wings shredded by the ground troops’ gunfire. Reports of enemy forces concentrated at several points around the Sinai Peninsula drove the British to reassess their defences along the canal.40

The Suez Canal runs one hundred miles from Port Said on the Mediterranean to Suez on the Red Sea. The canal joins two large saltwater lakes whose twenty-nine miles of marshy shores were ill-suited to military movements, and British engineers flooded ten miles of low-lying shores on the east bank of the canal, thus reducing the total distance to defend to seventy-one miles. The British decided to take advantage of the depressions on the north-eastern banks of the canal to flood a twenty-mile stretch, further reducing the area to be defended to just fifty-one miles of the canal. British and French warships deployed to key points along the canal, between Qantara and Ismailia, to the north of Lake Timsah, and between Tussum and Serapeum, to the north of the Great Bitter lake, where the British believed an attack would be most likely. Indian troops were reinforced by Australians and New Zealanders, as well as a battery of Egyptian artillery.41

With some incredulity, British forces waited to see what the Ottomans would try to do next. H. V. Gell, the young signals officer who had taken part in the action off Aden, was posted to the northern Suez Canal near Qantara. Though eager enough to “see some action”, Gell makes clear in his diary that neither he nor his commanders had any idea what the Ottomans were up to. He recorded a series of minor skirmishes and false alarms in the last days of January 1915. While patrolling the West Bank of the canal in an armoured train on 25 January, he received an urgent message from brigade headquarters: “Return camp immediately. Kantara being threatened in earnest by real enemy.” False alarm. On 26 January, while British positions came under artillery fire from Turkish guns, Gell was dispatched to a post several miles south of Qantara. “Hear 3000 enemy are reported near Ballah,” he noted. Increasingly concerned by reports of enemy soldiers in the Sinai, the British did not know where the Ottomans were, what their numbers were, or where they planned to attack. To that extent at least, Cemal Pasha had achieved a degree of surprise.42

As a precaution, the British withdrew all their troops to the western shores of the Suez Canal. They left dogs chained at regular intervals on the east bank of the canal to bark at any approaching men. In the event of a night attack, airplanes would be of no use in spotting troop movements, and old-fashioned guard dogs would have to do.43

On 1 February, Ottoman commanders issued the orders for the attack. To maintain the element of surprise, “absolute silence must be preserved by both Officers and men. There must be no coughing, and orders are not to be given in a loud voice.” Soldiers were to wait until they had crossed from the east to the west bank of the canal to load their weapons, presumably to avoid accidental gunshots that would alert the British defenders. Cigarette smoking was also forbidden—a hardship for the nerve-bitten soldiers. All

Ottoman troops were to wear a white band on their upper arms as a distinguishing mark to avoid friendly fire. As a play on the symbolism of jihad, the password for the attack was “The Sacred Standard”.

“By the Grace of Allah we shall attack the enemy on the night of the 2nd-3rd February, and seize the Canal,” the orders explained. While the main body was to attempt a crossing near Ismailia, diversionary attacks were to be made in the north near Qantara and to the south near Suez. Further, a battery of howitzers was to take up position near Lake Timsah to fire on enemy warships. “If it gets the opportunity, [the heavy artillery battery] is to sink a ship at the entrance of the Canal.” Seizure of the canal was but one part of the operation. Sinking ships to obstruct the canal was a far more realistic objective than the capture of well-entrenched British positions on the canal.44

The day before the attack, a sudden wind blew up, causing a heavy sandstorm that obstructed all vision. A French officer later claimed, “It was a terrible ordeal just to keep one’s eyes open.” The Ottoman and German commanders took advantage of the cover provided by the sandstorm to move their troops forward towards the canal at a point just south of Ismailia, before the wind died down for a clear night. The conditions were perfect for the attack.45

“We arrived at the canal late at night,” Fahmi al-Tarjaman, a Damascene veteran of the Balkan Wars, recalled, “moving quietly with no smoking or talking allowed.”

No one was to make a single sound walking across the sand. A German came along. We were to lower two of the metal boats in the water. The German took one to the other bank and returned after about an hour.

He picked up the second one filled with soldiers and also took it across to the other side. As each boat was filled he would drop the soldiers on the other side of the canal. In this way, by taking the full boats over and returning empty he took two hundred and fifty of the soldiers to stand guard around the work site to prevent anyone from interfering.46

The crossing took more time than the Ottoman commanders had expected, and by daybreak they were still assembling the pontoon bridge across the canal. Silence on the west bank of the canal confirmed the Turkish attackers’ belief that they had crossed an undefended stretch of the canal. A group of jihad volunteers from Tripoli in Libya, who called themselves the Champions of Islam, broke the silence, shouting slogans to encourage each other. In the distance, dogs started barking. And suddenly, as the sixth boat joined the pontoon bridge, the western bank of the canal erupted in machine-gun fire.47

“The bullets were all over, hitting and exploding in the water and making the water of the canal churn like a kettle of boiling water,” Fahmi al-Tar-jaman recounted. “The boats were hit and started sinking and most of our men could not shoot back although those who could did. Those who could swim saved themselves but those who could not drowned and went down with the boats.” Tarjaman and a group of soldiers ran from the exposed coastline “faster than we had ever run before”. He saw a group of armoured ships coming up the canal with their guns pointing towards Ottoman positions. “Above us planes began bombarding us, along with the ships from the water.” A telegraph operator, Tarjaman set up his equipment from the relative shelter of the dunes behind the canal and “made contact with the troops behind us to apprise them of the situation while the guns at the canal continued all the while dropping shells on us”.48

Some of the heaviest firing against Ottoman positions came from an Egyptian artillery battery that had dug into a position high on the west bank of the canal with a commanding view over the Ottoman pontoon bridge. Ahmad Shafiq, the veteran Egyptian statesman, recounted how First lieutenant Ahmad Efendi Hilmi ordered his battery to wait until the Turks had crossed the canal before opening fire but lost his life in the crossfire. Hilmi was one of three Egyptians killed and two wounded in the defence of the canal. The members of the 5th Artillery Battery were later decorated by Egyptian Sultan Fuad for their heroism. But Shafiq was quick to remind his readers, “The participation of the Egyptian Army in the defense of Egypt contravened the English pledge [of 6 November 1914] to bear the responsibility of the war themselves, without any assistance from the Egyptian people.” However much the Egyptians celebrated the valour of their soldiers, they resented the British dragging them into a war in which Egypt had no cause to fight.49

In the course of the battle on 3 February, British gunships destroyed all of the Ottoman pontoons. Those Turkish soldiers who had succeeded in crossing the canal were either captured or killed. Unable to fulfil the primary objective of securing a bridgehead over the canal, the Ottomans now focused their efforts on trying to sink Allied shipping to obstruct the waterway. The heavy howitzer battery got the measure of the British ship HMS Hardinge and scored direct hits on both funnels, damaging her steering and forward guns and knocking out her wireless communications. In imminent risk of sinking, Hardinge raised anchor to retreat to the safety of Lake Tim-sah, beyond the reach of Ottoman artillery.

The Ottoman battery turned next to the French cruiser Requin and pounded the ship with dangerous accuracy. Only when the French spotted a puff of smoke marking the location of the Ottoman guns were they able to return fire and silence the howitzers. Meanwhile, lighter artillery levelled accurate fire on the British ship Clio, which took several direct hits before it too managed to locate the Ottoman guns and destroy them.50

By early afternoon, all Ottoman ground attacks had been repulsed by the British, and most of the Turkish artillery batteries had been destroyed. In his headquarters, Cemal Pasha convened a meeting of Turkish and German officers. The Turkish commander of the VIII Corps, Mersinli Cemal Bey, argued that the army was no longer in any position to continue fighting. Cemal’s German chief of staff agreed and proposed an immediate end to the fighting. Only Mersinli Cemal Bey’s German chief of staff, Colonel von Kressenstein, insisted on pursuing the offensive to the last man. He was quickly overruled by Cemal Pasha, who argued that it was more sensible to preserve the Fourth Army for the defence of Syria and called for a retreat to begin as soon as darkness fell.51

The British, expecting the attack to be renewed on 4 February, were surprised to see that the bulk of the Turkish force had disappeared overnight. As British forces patrolled the east bank of the canal, they surprised isolated detachments of Turkish soldiers who had not been informed of the retreat. However, the British decided not to chase the retreating Ottomans, still not knowing how many men were in the campaign army and fearing that the whole expedition might prove a sort of trap to draw British forces into an ambush in the depths of the Sinai. The Ottomans, for their part, relieved to see that the British forces were not in pursuit, slowly made their way back to Beersheba.

Casualties for both sides were relatively low. The British lost 162 dead and 130 wounded in the fighting on the canal. Ottoman casualty figures were higher. The British claimed to have buried 238 Ottoman dead and taken 716 prisoner, though many others were believed to have died in the canal itself. Cemal gave Ottoman losses as 192 dead, 381 wounded, and 727 missing.52

In the aftermath of defeat in the Caucasus and on the Suez Canal, Ottoman commanders in the ministry of war were determined to recover Basra from the British. The speed of the Anglo-Indian army’s conquest of southern Iraq had caught the Young Turks by surprise and revealed their vulnerability in the Persian Gulf region. The challenge was to retake Basra and repel the British from Mesopotamia with the fewest regular Ottoman troops possible. Enver Pasha, the minister of war, entrusted the mission to one of the leading officers in his secret intelligence service, the Te§kilat-i Mahsusa (Special Organization). His name was Suleyman Askeri.

Born in the town of Prizren (in modern Kosovo) in 1884, Suleyman Askeri, son of an Ottoman general and graduate of the elite Turkish military academy, was the consummate military man. Even his surname, Askeri, meant “military” in Turkish and Arabic. His revolutionary credentials were impeccable. As a young officer, Askeri served in Monastir (today the town of Bitola in modern Macedonia) and took part in the Young Turk Revolution in 1908. He subsequently volunteered as an officer in the guerrilla war against the Italians in Libya in 1911.

World History

World History