While Napoleon was organizing his war effort and confronting the Legislative Body, the allied armies, almost 200,000 strong, were advancing deep into eastern France. Along the whole front they were only opposed by 70,000 French troops, who prudently retreated before them. By 18 January, Bliicher had reached Joinville on the river Marne, while to the south Schwarzenberg, with the main body, had occupied the strategic plateau around Langres.1

This easy progress had a powerful effect at allied headquarters, and particularly on the Czar, who arrived in Langres on 22 January. Alexander saw his ultimate goal, a triumphal march on Paris and the overthrow of his great enemy Napoleon, within his grasp. He even began to look beyond this, and revived his old idea of placing Bernadotte, who would be an obedient Russian client, on the French throne. His determination to press on was mirrored by Bliucher. The Prussian commander was burning to avenge Prussia’s humiliating defeats by Napoleon in 1806 by crushing him and seizing his capital. ‘The drive goes on to Paris’, he wrote on 14 January. ‘... I believe we will be strong enough to deliver a decisive blow that will decide everything.’2

These perspectives filled the Austrians with alarm. Their aim remained, as it had been at Frankfurt, to negotiate a compromise peace well before they reached Paris. Their desire to preserve Napoleon was only reinforced by their distaste for the replacement Alexander had in mind for him. ‘We have no interest in sacrificing a single soldier to put Bernadotte on the French throne,’ Metternich wrote to Schwarzenberg on 16 January. ‘You think I’m mad? Well, I’m not; this is the plan!’ Schwarzenberg was equally horrified. ‘I’ve received your letter,’ he replied, ‘... and ever since I can’t get B[ernadotte] out of my mind. What! The world has witnessed an alliance

Map 10. The campaign of France, 1814.

Between the greatest sovereigns of Europe to arrive at such a scandalous result!!! Impossible! I count on you [to avoid it].’3

At this critical moment, Metternich was reinforced by a powerful new ally. On 18 January, the English foreign minister, Lord Castlereagh, joined him at Basel after a gruelling three-week journey from London in freezing winter weather. Temperamentally, the serious, taciturn Castlereagh was very different from his extrovert Austrian counterpart, but politically both men were cautious and pragmatic, and to Metternich’s delight soon found common ground on the questions before them. ‘I cannot praise Castlereagh enough’, Metternich wrote on 30 January. ‘His attitude is excellent and his work as direct as it is correct... his mood is peaceful, peaceful in our sense.’4

The essential point was that Castlereagh found the prospect ofBernadotte as king of France as unacceptable as did Metternich. The two differed about the alternative: Castlereagh supported a Bourbon restoration as the best guarantee of peace, whereas Metternich’s preferred option remained a Napoleonic France reduced to acceptable limits. Faced with the threat of Bernadotte, however, they swiftly arrived at a compromise. They decided that there were only two choices to rule France—Napoleon or the Bourbons. Which one was a matter for the French people. If the allies were seen to interfere, it could cause a patriotic backlash which Napoleon would be sure to exploit. In the meantime, unless and until Napoleon’s authority was successfully challenged from within, the allies should continue to negotiate with him.5

Other critical questions were discussed in the same spirit of cooperation. Castlereagh’s main aim was to ensure, in the wake of Aberdeen’s blunder at Frankfurt, that England’s maritime rights were maintained intact in any peace settlement. Recognizing the English government’s intractability on this point, Metternich gracefully conceded it. On the issue of France’s future borders, however, there was a wider gap. Metternich had endorsed the ‘natural frontiers’ at Frankfurt, while Castlereagh followed the policy set out by his mentor Pitt the Younger nine years before. This favoured returning France to her ‘former limits’ of 1792, before the revolutionary wars.6

Both men, however, were prepared to make concessions. With the crossing of the Rhine, France’s ‘natural frontiers’ had already been breached, and Metternich realized that it was now probably impossible to obtain them in their entirety. Castlereagh too was willing to be flexible, provided Antwerp was taken from France and a solid ‘barrier’ created in the Low Countries to protect England from future invasion. This was perfectly in

Keeping with Pitt’s policy, which had been less committed to imposing France’s ‘former limits’ than is generally acknowledged.7 Even Pitt had accepted that this could prove impossible in practice, and that part of the Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine might have to remain in French hands.

On this basis, in the course of a week in Basel, Metternich and Castle-reagh discussed the outline of new frontiers for France, marking a compromise between her ‘natural’ and her ‘former’ limits. She would lose Mainz, but retain a substantial chunk of territory on the left bank of the Rhine up to the river Moselle. Holland would be given a strong barrier against France, including Antwerp. No precise line for the future Franco-Dutch border was mentioned, but shortly afterwards Castlereagh proposed that it should be the river Meuse. These discussions were soon overtaken by events, but show that Castlereagh was at least prepared to consider a significantly more generous settlement for France than her pre-1792 boundaries.8

More immediately, the Czar’s plan for an immediate drive on Paris to dethrone Napoleon had to be scotched. On the night of 22 January, Metternich and Castlereagh left Basel, and arrived at Langres three days later. There they found Schwarzenberg thoroughly angry and upset. He was still committed to Metternich’s plan for a limited invasion of France and compromise peace well before Paris was reached. For three days Alexander had given him no peace, constantly pressing him to change his strategy and march on the capital. Schwarzenberg held firm, but his exasperation with the Czar was obvious. ‘We should make peace here; that’s my opinion,’ he wrote to his wife on 26 January, ‘any advance on Paris would be against all military principles. . . but Czar Alexander has had another of those fits of buffoonery that often seize him. This is an absolutely decisive moment; may Heaven protect us in this crisis.

The same day, Schwarzenberg sent Francis I a long memorandum setting out the case for and against an offensive on Paris. He nowhere stated, but it is highly likely, that it had been concerted beforehand with Metternich and Castlereagh. He awaited Francis’ decision whether to remain on the plateau of Langres or ‘descend into the plain and begin the struggle’, but made his own preference clear. He needed time to rest his troops, bring up reinforcements, and establish closer contact with both wings of his army. In the flat lands between the plateau and the capital, there were no obvious points where his forces could halt and regroup. Langres was therefore the last position from which peace with Napoleon was possible. Furthermore, as

The allies advanced deeper into France, the likelihood of a popular rising against them would increase. For Schwarzenberg, the dangers of going forward far outweighed the benefits.10

Although Schwarzenberg was careful to concentrate on military matters, the issues he raised were clearly political. Staying put implied negotiating with Napoleon; advancing would be a long step towards his overthrow. Francis sent the memorandum to Metternich for his views. These, along with his own decision, he then forwarded to Alexander, Frederick William, and Castlereagh. Metternich concluded his comments with a series of questions designed to pin down the Czar. The most important were whether the allies wished to negotiate peace with France on the basis of the natural frontiers, whether they aimed to change her ruling dynasty, and if so whether in favour of the Bourbons or another candidate. Francis’ answers were clear—the allies should leave the dynastic question to the French themselves, and begin peace talks with Napoleon. They should also swiftly decide how far, if at all, France should be allowed to retain the natural frontiers. Of the other allied monarchs, only Alexander clearly opposed these proposals.11

On two successive evenings, on 27 and 28 January, Metternich had long interviews with the Czar. Both were stormy. Alexander argued fiercely against a Bourbon restoration. Instead, once Paris had been captured, he proposed to caU a representative assembly. In this way the French people themselves could choose their form of government and ruler, but on the understanding that both a republic and Napoleon would be excluded. Bernadotte was not directly mentioned, but a Parisian parliament surrounded by Russian troops was unlikely to choose any other candidate.

Metternich’s reply was forthright. Calling an assembly in Paris would simply revive the instability and factionalism of the revolutionary era, and could under no circumstances be considered. He even made the ultimate threat available to a coalition partner: if Alexander persisted with his plan, Austria would withdraw. Faced with this, the Czar was forced to concede, and a compromise was reached. The idea ofan assembly, and by implication Bernadotte, was dropped. Instead Caulaincourt, who had already left Paris expecting a negotiation, would be invited to a peace conference at ChatiUon-sur-Seine, between Langres and the capital. However, in accordance with the Czar’s wishes, the allied advance would resume. By insisting on this Alexander showed considerable acumen. If fighting continued, the peace terms would vary according to the fortunes of war. The decision

Would shift from the conference table to the battlefield and here, the Czar was confident, the allies’ numerical superiority would ensure Napoleon’s defeat and overthrow.12

With these questions resolved, the ministers of the four Powers met the next morning to discuss the most important remaining issue—that of France’s future borders. Having pondered his previous conversation with Metternich, Castlereagh felt that the territories to be allowed to France beyond her ‘former limits’ needed to be reduced. Unwilling to alienate such a useful ally, Metternich acquiesced. However he still urged, as Castlereagh described it, ‘some concession to France, neither extensive nor important in itself, beyond the ancient limits. .. [indicating] some portion of the flat country of Savoy and possibly some portion of territory on the left bank of the Rhine.’13 This showed that Metternich realized the importance of the Rhine and the Alps to Napoleon. If the allied peace terms made a gesture, if only a symbolic one, towards them, he could still proclaim that national honour had been saved. The meeting accepted Metternich’s proposal.

Over the next few days, events turned sharply in the allies’ favour. Arriving at the front on 26 January, Napoleon decided to exploit the gap between the two invading armies and turn on Bldcher. The first engagement, however, was indecisive. It took place on 29 January at Brienne, at whose military academy Napoleon had spent his schooldays. The Prussian and Russian troops finally withdrew, but in good order, and not before Napoleon had almost been captured by a party of Cossacks, and Berthier wounded in the head and knocked from his horse. Worse followed for the French three days later. Reinforced by Schwarzenberg, Bliicher went on the offensive, and caught Napoleon by surprise. At La Rothiere just outside Brienne, in blizzard conditions, 40,000 French faced 53,000 allies, whose numbers rose during the day to 110,000. By the afternoon the French right wing was starting to give way, and Napoleon had no option but to retreat. His losses were roughly equal to his opponents’—6,000 dead and wounded— but he had clearly been defeated.14

The news of La Rothiere caused jubilation at allied headquarters. Napoleon had been beaten on his native soil, and the road to Paris seemed to lie open. However, Caulaincourt had now been invited to a peace conference, and this promise had to be honoured. On 3 February, the allied representatives arrived at Chatillon—for Austria Stadion, Metternich’s predecessor as foreign minister; for Prussia Humboldt, who had already taken part in the congress of Prague; for Russia Count Razumovsky, a known

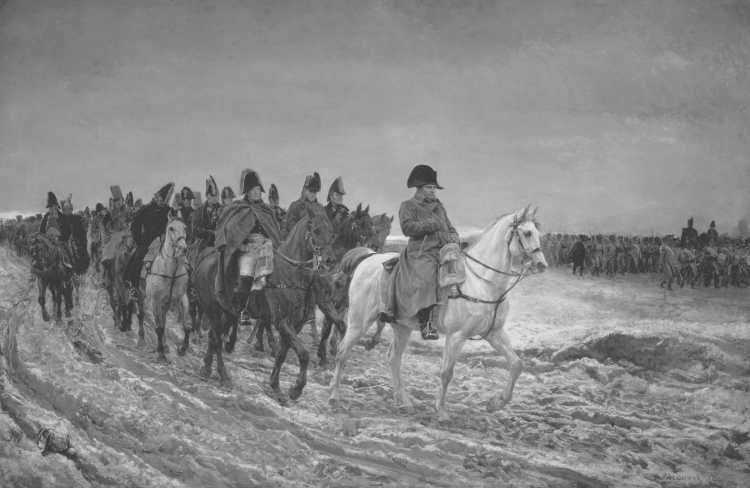

Figure 9. Campaign of France, 1814, by Jean Louis Meissonier.

Francophobe; and for England no less than three envoys, Cathcart, Stewart, and Aberdeen. Caulaincourt was waiting for them, having arrived at Cha-tillon a fortnight before. Underlining how desperately most French people wanted the war to end, in the towns en route from Paris he had been acclaimed by crowds shouting ‘Long live peace!’15

The envoys and their substantial entourages were billeted around the town. Caulaincourt was assigned the largest house, that of M Etienne, a rich merchant. The conferences were held in the mansion of a local noblewoman, Mme de Montmaur. Chatillon itself, being in a war zone, was a ghost town. The peasants had fled, there was no market, and hence no food. ‘We are bringing our own provisions as if we were travelling to the Indies,’ wrote Stadion to his wife. In this depressing atmosphere, the congress opened on 5 February, only to be adjourned after twenty minutes because Razumovsky claimed that his instructions had not yet arrived. Then, as soon as Caulaincourt had left the room, Castlereagh declared to his allies that even if Napoleon accepted all their terms, England could not sign until all aspects ofthe settlement, even those unconnected with France,

Had been agreed. However accommodating Caulaincourt proved to be, there would still be a significant delay before any treaty was concluded.16

At this moment Caulaincourt’s main concern was not the other Powers, but his own master. He was desperately worried that even in defeat Napoleon might still risk his future in battle rather than entrust it to diplomacy. Once again, he joined forces with Berthier to make the Emperor see reason. ‘Bring the truth home to His Majesty,’ he wrote to the marshal on 3 February, ‘convince him how serious the situation is, and how much any delay will risk to no advantage. TeU me truthfully... do you stiU have an army? Can we discuss conditions for a fortnight or should we accept them straight away? If no-one has the courage to teU me where we reaUy stand, I am left with... no idea what I should do.’17

In these perilous circumstances, what Caulaincourt needed were plenipotentiary powers, enabling him to sign a peace without referring the terms back to Napoleon. On 4 February he wrote the Emperor begging for these. Initially, Napoleon brushed the request aside. Discussing it with the Duke of Bassano, he pointed at a passage from Montesquieu’s Grandeur et Decadence des Remains at his elbow. This described Louis XIV’s attitude when France was invaded in 1709: ‘I know of nothing so magnanimous as the resolution taken by one recent monarch, to bury himself beneath the ruins of his throne rather than accept proposals that no king should have to hear.’ Yet Bassano, in a courageous outburst that belied his reputation as a warmonger, threw the quotation back at Napoleon: ‘I know of something even more magnanimous—to throw down your glory to close the abyss into which France risks falling with you!’ Throughout most of the night he argued with the Emperor, and finally extracted a letter giving Caulaincourt carte blanche to sign whatever terms he saw fit, which was sent the next day. It was Bassano’s greatest contribution to peace in 1813-14.

The crucial session of the congress opened at midday on 7 February. To his horror, Caulaincourt found that the offer of the natural frontiers no longer held. Instead, the allied representatives demanded the ‘former’, prerevolutionary, frontiers ofFrance. All that was left ofthe Frankfurt proposals were ‘arrangements of mutual convenience concerning portions of territory on both sides of these limits’—a phrase Metternich had inserted into the instructions for the conference, presumably indicating the ‘flat lands of Savoy’ and parts of the left bank of the Rhine he was prepared to concede. Shocked, Caulaincourt could only reply: ‘Today’s stipulations differ so

Greatly from the bases proposed to M de St Aignan [at Frankfurt] ... that they are completely unexpected.’

Having recovered, Caulaincourt sought one crucial clarification. If he accepted the terms, he asked, would a treaty be signed immediately, ending the bloodshed? This was precisely the issue the allies wished to avoid. Castlereagh’s stipulations two days before had made a delay inevitable, and it was clear that the Russians were in no hurry to make peace with Napoleon, especially since they believed his fall to be imminent. Razumovsky had just received a letter from Nesselrode, telling him of the capture of several strategic French towns and instructing him to slow down the negotiations. Caulaincourt thus received an evasive answer, and asked for time to reflect, which was willingly granted. The session resumed at 8 p. m., but broke up with no further decision reached.20

Caulaincourt now had the carte blanche he wanted, but hesitated to use it. He had expected to sign peace on the basis of France’s ‘natural frontiers’, but now found that only her ‘former limits’ were on offer. Accepting these immediately was a fearful responsibility, and he baulked at it. They had never been discussed with Napoleon, who might well disavow him. Caulaincourt decided he could only accept the terms with Napoleon’s express permission. Immediately after the evening session ended, he sent a despatch detailing the proposals to his master, asking for further instructions. He could only hope that Napoleon would accept the seriousness of the situation, and give a swift and positive answer.21

On 7 February, Napoleon arrived at Nogent-sur-Seine, north-west of Chatillon, and received Caulaincourt’s report late that same evening. He read the letter, then went into his room without a word and shut the door. Berthier and Bassano joined him shortly after and found him at his desk with his head in his hands. He showed them the terms, and after a long silence they both urged him to accept them. Napoleon’s response was a passionate tirade:

What! You want me to sign such a treaty, and trample underfoot my coronation oath? Unprecedented defeats may have forced me to promise to renounce my conquests, but to abandon those of the Republic! To betray the trust placed in me with such confidence! To... leave France smaller than I found her! Never!... What will the French people think of me if I sign their humiliation? What shall I say to the republicans in the Senate when they ask me once more for their Rhine barrier? ... You fear the the war continuing, but I fear much more pressing dangers, to which you’re blind.22

The coronation oath to which Napoleon referred bound him to ‘maintain the territorial integrity of the Republic’, which meant above aU the natural frontiers. If he broke it and returned to the pre-revolutionary limits, he feared that his regime might not survive. This was the ‘pressing danger’ that alarmed him more than the prolongation of the war. He even named the men who would lead the movement against him—the ‘republicans in the Senate’ like Sieyes, Garat, and Gregoire, who had never forgiven him for returning to a form of monarchy and would seize this chance to take their revenge. The empire would be overthrown and the Republic restored, under the banner of a patriotic war to regain the boundary of the Rhine.

In a gesture of despair, Napoleon threw himself on his bed, and continued to argue furiously with Berthier and Bassano. Eventually, after several hours, they managed to wear him down. It was agreed to accept the terms, giving up Belgium first and then, if this did not satisfy the allies, surrendering the left bank of the Rhine as well. Napoleon and his advisers also recognized that Germany and Italy were now irretrievably lost. In the early hours of the morning, Bassano left the Emperor’s bedside to draft the necessary instructions to Caulaincourt.

In his manuscript notes, Laine had argued that Napoleon’s unwillingess to make peace was entirely cynical, since war abroad gave him an excuse to maintain his tyranny at home. Napoleon’s behaviour on 7—8 February offers compelling evidence that even if this was partially true, it was not the whole story. That night Napoleon appeared in genuine agony, convinced that if he accepted the terms before him, he would exchange the prospect of military defeat for one he feared more, domestic upheaval. After dismissing Berthier and Bassano, he tried to sleep, but was unable to do so, calling in his valet ten times, either to bring him a light or to take it away. His thoughts turned to death, both his own and his son’s. At four in the morning, he wrote a melodramatic letter to his brother Joseph in Paris:

Paris will never be taken while I am alive... If news arrives of my defeat and death, you will be told before the rest of my household: send the Empress and [my son] the King of Rome to Rambouillet... Never let the Empress and the King of Rome fall into the enemy’s hands... That would destroy everything...

I would prefer my son’s throat to be cut than to see him raised in Vienna as an Austrian prince.

I have never seen a performance of Andromaque without pitying the fate of Astyanax [the son of Hector, captured after the fad of Troy] outliving his family, and without thinking that he would have been better off dying with his father.2

Then, at around 7 a. m., there was a dramatic reversal of fortune. A messenger arrived from Marshal Marmont with news that BlUcher, in his haste to reach Paris, had allowed the four army corps he commanded to become widely separated. Napoleon leaped out of bed; this was the chance he had hoped for, and he immediately began to plan exploiting it. When Bassano, who had been working the rest of the night writing up Caulain-court’s instructions, arrived to have them signed, Napoleon waved him away: ‘Oh, there you are! Things have moved on. I’m facing down Bliicher! I’ll beat him tomorrow or the day after; everything’s going to change. Let’s not hurry anything. There’ll be plenty of time to take the peace on offer later!’24 The diplomatic humiliation he dreaded had receded, and he was returning to the place where he felt happiest, the battlefield.

At Chatillon, there were no conferences on 8 or 9 February, as the allied diplomats discussed how to respond to Caulaincourt’s request for an immediate signature ofpeace. On the 9th, Engelbert von Floret, Stadion’s deputy, visited Caulaincourt to keep him informed. He was greeted with a diatribe showing that at least one of Napoleon’s servants shared his fears that a harsh settlement would reignite the French Revolution. ‘Ha, M de Floret,’ Caulaincourt burst out, ‘you are preparing great misfortunes for us and for yourselves. You saw the need to end the Revolution, you did so in the noblest way by marrying an Archduchess to [Napoleon], and now you’re in danger of rekindling it with all its horrors.’ Later that day Caulaincourt’s assistant Rayneval spoke to Floret in similar terms: ‘Your policy could have terrible consequences. Today you can still avoid them, but soon. . . this will be beyond your power. You are lighting a fire that you will be unable to put out and which could spread further than you think. It’s not the Bourbons I fear, they have no chance, but disorder, a new overthrow of the social order.’25

Floret was impressed by these warnings. ‘Unfortunately’, he wrote, ‘I could think of little to say in reply to them.’ His concerns were not shared by his Russian colleague. Convinced that Napoleon was about to fall, Razumovsky pressed for the congress to be temporarily halted. Stadion, however, strongly opposed this. The deadlock was broken on 8 February when Razumovsky received instructions from the Czar, saying that he did not feel able at present to answer Caulaincourt’s request for an immediate peace treaty, and that the conferences should cease until further notice. The next day Razumovsky read out this letter to the other allied envoys, who were completely taken aback; Stadion especially was furious. But little could

Be done. Alexander was clearly determined to march on Paris, and for the moment could not be gainsaid. On 10 February, the negotiations were suspended.26

This brought about a second and even more furious clash between Alexander and his allies. Metternich and Castlereagh rightly sensed he was making a second attempt, emboldened by military success, to overthrow Napoleon and replace him by Bernadotte. They swiftly coordinated a counterattack. On ii and 12 February, Castlereagh had two long meetings with the Czar, at which he argued strongly for continuing negotiations with Napoleon. At a ministerial conference on the 13 th, Metternich again played his trump card, bursting out that ‘Austria would not tolerate this [Russian] tyranny, and would withdraw its army from the coalition and make a separate peace with Napoleon.’ He then proposed an ingenious compromise: a preliminary treaty with France. This had two advantages. Though it still meant a settlement with Napoleon, it was less binding than a full treaty and thus answered Castlereagh’s doubts about signing a complete settlement immediately. Also, since it did not entail an armistice, the Czar could go on hoping that the war could still topple Napoleon. The basis of the preliminaries would, once again, be France’s former limits. Realizing he was isolated, Alexander gave way. The preliminary treaty was drafted, and sent for discussion at Chatillon.27

At Troyes, the allies were looking forward to military victory, but as they were discussing and arguing, it was slipping from their grasp in the field. On 9 February, Napoleon had left Nogent-sur-Seine and headed north-east, aiming to catch Bliicher’s army strung out on the march. The next morning he caught the most isolated corps, commanded by the Russian General Olsufiev, at Champaubert. It was overhwelmed, and Olsufiev experienced the humiliation of being captured in a wood by a 19-year-old French conscript. With his own troops concentrated in the middle of the scattered enemy forces, Napoleon was now able to pick them off at will. The next day he moved west to attack General von der Osten-Sacken’s corps at Montmirail. The day was decided by a charge of six battalions of the Imperial Guard led by Ney, which sent the allies reeling back, and was completed by a ferocious pursuit. On 14 February, Napoleon defeated Blucher himself, who was hurrying westwards to retrieve the situation, at Vauchamps. Bliucher’s right wing was broken by a crushing French cavalry charge, and he had to make a fighting retreat. In just six days, he lost a third of his total force.28

This extraordinary week re-established Napoleon’s military reputation after La Rothiere, and remains one of his most brilliant displays of generalship. However to the south the French forces, under Marshals Victor and Oudinot, were being pressed hard by Schwarzenberg. Napoleon now turned to face this threat, and on 18 February attacked one of Schwarzen-berg’s corps, commanded by Prince Eugen of Wurttemberg, at Montereau. After a heavy artillery duel, the French stormed the main allied position on the plateau of Surville, with Napoleon himself helping to position the guns to exploit this success. When Schwarzenberg heard of this reverse, he was shaken. Always a cautious general, he pulled his whole army back behind the river Seine.

The series of allied defeats spurred Schwarzenberg to a further action, which was highly significant and which he seems to have taken on his own initiative. He went to Alexander and Frederick William, who were at his headquarters, and proposed an armistice. This was an extraordinary move, since it cut completely across the decision taken at Troyes just three days before, to work instead for a preliminary treaty. It betrayed Schwarzenberg’s exasperation with the slowness of the diplomats at Chatillon. Even more extraordinary, Alexander and Frederick William immediately agreed to the plan. This was a measure of their consternation at Napoleon’s resurgence, and of how brittle their earlier confidence had been. As a result, having first been unsure about whether to negotiate with Napoleon at all, the allies now found themselves committed to not one, but two, peace overtures towards him, the first aiming at a preliminary peace, the second at an armistice.

Yet an armistice had one advantage, which reveals Schwarzenberg’s shrewdness in suggesting it. It would end the fighting, so that diplomacy would no longer be at the mercy of the events of war. Up until now, both sides had been gambling on outright military victory, altering their terms and delaying conferences in accordance with news from the battlefield. With these temptations removed, negotiations could become simpler and more straightforward. Schwarzenberg’s initiative thus offered the best available hope of peace.

At Troyes, Metternich was furious that his own policy had been upstaged, but could do little about it. With Alexander, Frederick William, and Schwarzenberg ranged against him, he had to accept that for the moment the congress of Chatillon was eclipsed. Castlereagh was also angry, but equally impotent. The diplomats convened just once at Chatillon on 17 February to present the preliminary treaty to Caulaincourt, who Replied that he would have to consider it and consult Napoleon. The conferences then adjourned once again, as attention shifted to the armistice

Negotiations.

Caulaincourt had temporized with good reason, since he no longer had carte blanche to conclude an agreement. Five days before, buoyed up by his victories at Champaubert and Montmirail, Napoleon had written to him that the only possible basis for peace now was the natural frontiers, and that any other treaty ‘would be merely a truce’. On 17 February, he formally rescinded Caulaincourt’s powers, and instructed him ‘to sign nothing without my order, since I alone know my position’.31 Ironically, this placed the allies in exactly the same situation Napoleon had been in two weeks before, desperate for a settlement that their opponent was unwilling to accord. Napoleon’s change of stance should not have been unexpected. He had only momentarily considered abandoning the natural frontiers under extreme pressure, on the night of 7—8 February. Now, with the military situation restored, he returned to them as his sine qua non for peace. As the heir of the Revolution, with all that entailed, he felt he could retreat no further.

Further proof of Napoleon’s renewed intransigence soon followed. On 21 February, he sent a long letter to Francis I, invoking family ties and attempting to divide him from his allies. ‘I propose to Your Majesty’, he wrote, ‘that, without delay, we sign a peace on the bases you yourself established at Frankfurt, and which I and the French nation have adopted as our ultimatum.’ He blocked every avenue of compromise on these conditions: ‘I shall never cede Antwerp or Belgium.’ To deter Francis from advancing on the capital, he shamelessly conjured up the spectre of the Revolution and the sans-culottes: ‘There are 200,000 men under arms in Paris.’ The letter, with its hectoring tone, had the opposite effect on Francis than the one intended. It alienated him, and made him despair of any meaningful negotiation with his son-in-law.32

After Schwarzenberg proposed the armistice to Berthier, as Napoleon’s chief of staff, he was kept waiting five days. Berthier then sent him a blustering reply, clearly dictated by Napoleon himself, vaunting the strength of the French army and its latest victories. He also did not fail to mention ‘the armed population’ of Paris. Schwarzenberg persevered, and armistice negotiations began on 24 February at Lusigny a few miles east of Troyes, but the first French condition was that the natural frontiers be explicitly recognized as the basis of any future treaty. Since the allied representatives were all soldiers rather than diplomats, they replied, quite reasonably, that this was

Beyond their competence. They referred the matter back to their headquarters, and were told firmly that all political questions should be kept out of the talks.33

Fortune might have swung back to Napoleon’s side, but he did not feel strong enough to break off the discussions just yet, and agreed that the natural frontiers should not be mentioned. Instead, the issue simply reappeared in a different form over the question of the armistice demarcation line. Napoleon saw this as a means of staking his claim to the natural frontiers in a final settlement, and was determined that it should follow them as closely as possible. In the words of his secretary Baron Fain, he ‘sought to profit from the occasion to lay the basis of a definitive peace. He wanted to keep Antwerp and the Belgian coast: this was the reward he expected for his recent successes.’ For the same reason, he also wanted to keep Savoy on the French side of the line. The allied envoys refused to accept this, and on 5 March, after several days of fruitless wrangling, the Lusigny negotiations broke up.34

The failure of Lusigny was a body blow to moderates on both sides. One reason why Schwarzenberg pressed for an armistice was probably because it meant dealing with his friend Berthier, whom he knew to favour a swift peace. Berthier’s letter to Schwarzenberg had been uncompromising, but since it had obviously been inspired by Napoleon it did not have to be taken at face value. One sign that Berthier genuinely wanted a settlement was that he sent as the French representative to Lusigny his own adjutant, General Charles de Flahaut, Talleyrand’s illegitimate son and another member of the ‘peace party’. Flahaut did everything he could to keep the talks alive. Certainly he was seen as an ally by the Austrian envoy, General Duka, Francis I’s personal military adviser. Duka several times spoke to Flahaut in private, and his words could unofficially be taken as those of his master. As Flahaut related in a confidential report:

,35

He told me of the Emperor of Austria’s sincere desire to end the war. He said that his master had never [wished] to march on Paris. He cited as proof how slowly Prince Schwarzenberg was advancing. He repeated several times that he had no doubt peace could swiftly be concluded, if we could put a stop to the fighting, that the Emperor of Austria wanted this, and that [his peace terms] would be very reasonable. He returned to this subject every day, asking bluntly that we help the Emperor of Austria to make peace. ‘Ensure that hostilities end on the 28th,’ he told me, ‘give us the means of making peace: I swear to you that the Emperor of Austria and England wish it to be

Honourable for France.

On the evening of 28 February, all three allied representatives came to Flahaut and echoed Duka’s words, saying that if only an armistice could be agreed a moderate peace would certainly follow. Flahaut was later blamed for not signing then and there on his own authority, but this is unfair. Like Caulaincourt at ChatiUon a fortnight before, he was in a dreadful position; he knew that the only way to make peace was to go against his master’s wishes. Tragically, in these crucial months no-one in Napoleon’s entourage was prepared to do this, ensuring that the only solution left would be a military one.36

Schwarzenberg’s initiative was in ruins, but it had alarmed Castlereagh enough to take counter-measures. For the last year, the allies had been linked together by a complicated set of bilateral treaties, which had given Austria considerable leeway to pursue a separate policy towards Napoleon. Castlereagh proposed to reinforce these by a single general alliance between England, Austria, Russia, and Prussia. At Chaumont, where the monarchs and ministers now had their headquarters, after a week of intense discussions his plan was accepted. On 10 March, the treaty of Chaumont was signed, binding the allies not to make any separate peace until their common war aims had been achieved.37

The last act at ChatiUon could now begin. On 28 February, the conferences resumed; Caulaincourt again asked for more time to consider the preliminary treaty, and was given a deadline of 10 March. At 9 that morning he read out to the assembled diplomats a long memorandum repeating that the natural frontiers offered the only acceptable formula for peace. A long silence followed. Stadion and his colleagues realized the end had come, but they made one last effort. Caulaincourt was asked to produce a detailed counter-project to their own proposals, which he did five days later. This took the form of a full draft treaty, which still ceded almost nothing of the natural frontiers: Holland was given a barrier to the south, but France would retain Antwerp, most of Belgium, the left bank of the Rhine and Savoy. Beyond her borders, the kingdom of Italy would go to Eugene de Beau-harnais, and the king of Saxony would lose none of his territories. All the allied diplomats rejected this, and on 19 March the congress of ChatiUon was formally closed. The last peace negotiation between Napoleon and his opponents had failed.38

World History

World History