Theodore Roosevelt, the energetic and bellicose Assistant Secretary of the Navy, frequently dismayed President McKinley and John Long, McKinley’s able but conservative Navy Secretary. The President and the Secretary believed the time had come to curtail the naval building program, but Roosevelt, a friend and disciple of Mahan, argued that it should be expanded. McKinley and Long hoped and believed almost to the last that war with Spain could be averted. Roosevelt

George Dewey.

The Olympia, Dewey’s flagship.

Was convinced that it was inevitable and eagerly anticipated it. Despite their differences. Long greatly esteemed his young assistant. Roosevelt had early shown a firm grasp of naval principles in his book The Naval War of 1812, published when he was twenty-four years old. With such background, his vigor, enthusiasm, and quick mind enabled him, in long days extending far into the night, to do the work of several men.

McKinley and Long expected that, if war came, it would be confined to Cuba, with some action in nearby Spanish Puerto Rico. Roosevelt, taking a global view, fixed his attention on the Pacific Ocean area. At that time few Americans were aware that Spain had possessions in the Pacific, but Roosevelt knew that the Philippines were a Spanish colony and that the Spaniards had a small fleet in Philippine waters. Whether his objective was empire building or merely hitting Spain a secondary blow, we cannot be sure, but he personally decided that the U. S. Asiatic Fleet should attack the Spanish squadron in the Philippines.

Although he had no authority to do so, Roosevelt picked Commodore George Dewey, as aggressive and independent as himself, to command the Asiatic Fleet. He prevailed upon Dewey to request his senator to speak on his behalf directly to the President. At the same time he pigeonholed a letter favoring another candidate until Dewey’s appointment was assured.

After the sinking of the Maine, Roosevelt chafed at the Navy Secretary’s deliberateness of action. On the afternoon of February 25, Long happened to be away, leaving his assistant as Acting Secretary. Roosevelt seized the opportunity to fire off a whole series of peremptory orders that put the Navy on a full war footing. To Dewey, now at Hong Kong, he cabled: “Keep full of coal. In event of declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish Squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in the Philippine Islands.”

Dewey, on his own authority, had transferred the Asiatic Fleet from Yokohama to Hong Kong to be nearer the Philippines. He bought 3,000 tons of coal and then purchased the collier that brought it. He also acquired a supply vessel, to serve as fleet train. He had all engines overhauled, personally inspected all equipment and engine spaces, and conducted regular gunnery drills. He had underwater hulls scraped, ordered the white sides of his vessels to be painted battle gray, and made provisions for jettisoning wooden bulkheads and other combustibles. Lacking information about Philippine defenses, he got in touch with the U. S. consul at Manila, who at considerable risk undertook espionage activities and cabled or mailed his findings to Hong Kong. In short. Commodore Dewey prepared for action with all the meticulous attention to detail that he had seen exercised by his Civil War commander and idol, Admiral Farragut.

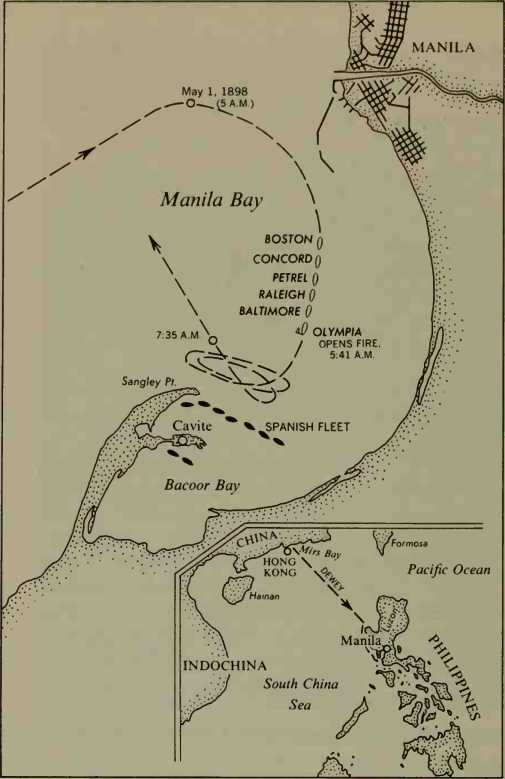

On the eve of war, the commodore prepared to avoid conflicts with British neutrality regulations by shifting his fleet to Mirs Bay, 30 miles up the Chinese coast. The general conviction at Hong Kong was that the Americans were going straight to destruction. After a farewell dinner tendered Dewey and his officers by a local British regiment, one of the hosts expressed the sentiment of all by remarking, “A fine set of fellows, but unhappily we shall never see them again.”

On April 25 came a cable from Secretary Long: “War has commenced between the United States and Spain. Proceed at once to the Philippine Islands. Commence operations particularly against the Spanish fleet. You must capture vessels or destroy. Use utmost endeavor. Dewey waited 36 hours in order to get from the American consul, then en route from Manila, the latest information on the state of Spanish defenses. On the 27th he headed for the Philippines.

Dewey’s combat vessels comprised four protected crusiers: the flagship Olympia (s>7So tons), the Baltimore, the Raleigh, and the Boston; and the gunboats Concord and Petrel. The squadron was armed with 53 guns ranging from five to eight inches. Six hundred miles away in the Philippines, Rear Admiral Don Patricio Montojo, well informed by his Hong Kong spies concerning the characteristics of the American squadron, estimated the American firepower at twice that of his own fleet. He therefore decided to fight near land, where shore batteries could supplement the inadequate fire of his ships.

On the evening of April 30, the American squadron was off the entrance to Manila Bay. Dewey had been informed that the channel was mined and that it was flanked by powerful batteries. In Hong Kong newspapers he had read stories from Europe about the power and effectiveness of the Spanish guns and minefield. The European news commentators concluded that Manila, so well shielded, was clearly impregnable. If Dewey should lose a ship or two going into the bay, the rest might well be destroyed inside. With home base 7,000 miles away, he could not be rescued or reinforced, nor could he be resupplied with ammunition. The decision on whether to enter was thus an appalling responsibility.

In fact, fleets do not normally enter harbors looking for enemy warships. The usual action in a situation such as Dewey faced was to blockade—a perfectly feasible operation for the commodore because his collier and supply ship were with him. A blockade would at least keep the Spanish fleet in port and out of mischief, and by causing shortages in Manila, would possibly wring extra concessions from the Spaniards.

On the other hand, Dewey was not worried about the minefield. He doubted that local engineers had the skill to plant mines in deep water. Furthermore, in tropical climates mines deteriorated rapidly. The batteries were another matter, for they could readily punch holes in his unarmored ships. As was his wont when faced with a perplexing situation, Dewey now asked himself, “What would Farragut do?” He knew perfectly well what Farragut would do. If the Admiral had dared to run past Fort Morgan and over a minefield by day, Dewey would certainly risk running past a few batteries by night. So, in the spirit of “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” he led the way into Manila Bay.

As the column of blacked-out ships entered the channel, Dewey’s gunners grew tense at their guns, but nothing happened. A little after midnight a stoker in one of the ships threw a shovelful of coal dust into a furnace, whereupon sparks spurted like fireworks out of the ship’s smokestack. One of the Spanish batteries then opened fire.

“Well, well,” said the commodore to Captain Charles Gridley, captain of the Olympia, “they did wake up at last.”

The Spaniards made no hits, and their battery was quickly silenced by gunfire from the ships. The entire American column passed into the bay unscathed. The squadron then slowed down to four knots in order not to reach Manila before dawn.

At first light Commodore Dewey could make out the city’s spires against a dim sky. Many merchant ships were present, but Montojo’s fleet, which Dewey had expected to find at Manila, was not there. The Spanish admiral had taken his ships south to Cavite in order to spare the city a bombardment. As the American squadron

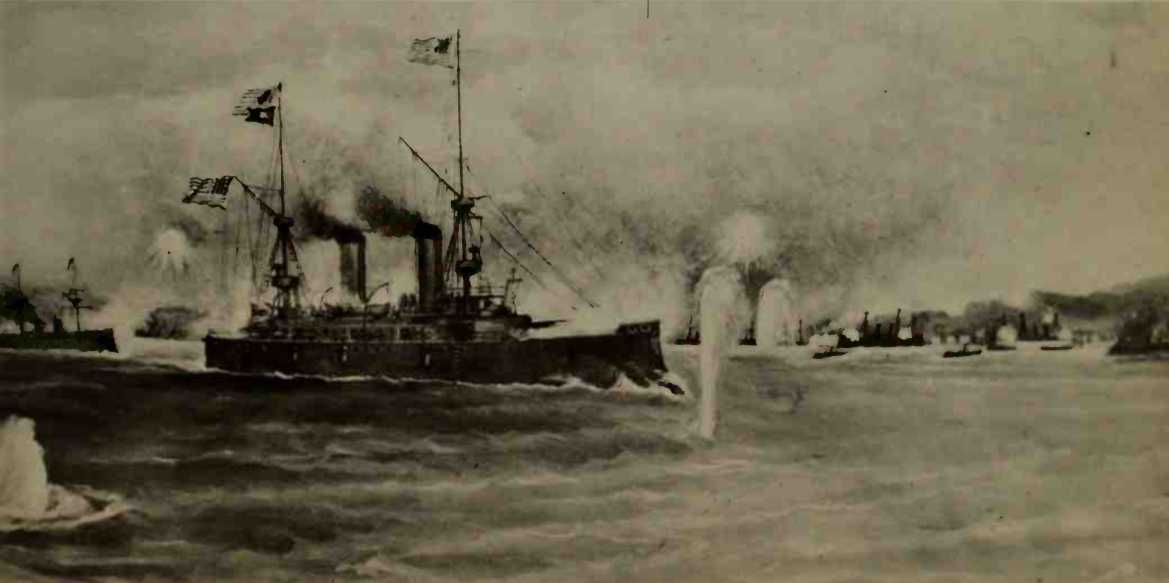

The Battle of Manila Bay. The Battle of Manila Bay, May i, 1898.

Wheeled to starboard and headed south, the Manila batteries opened fire with shell that passed harmlessly over the ships.

Shortly after 5 a. m., by the light of the rising sun, lookouts in the Olympia’s tops sighted the Spanish fleet —six cruisers and a gunboat—stretching in a rough crescent from Sangley Point across to shoal water near the mainland. In fact, all but two of the so-called cruisers were smaller than U. S. gunboat Concord. The two largest Spanish vessels were the Reina Cristina, Montojo’s flagship (3,520 tons), and the wooden Castilla, which was protected but also immobilized behind lighters filled with stones. Of the other vessels some were moored, others not.

Long before the Americans came within range, the nervous Spaniards opened fire. On the Olympia, up went the signal “Engage the enemy,” whereupon the national colors were hoisted on each American ship and bands struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner.” At the last note a lusty cheer sounded from every vessel, followed by the cry “Remember the MaineV’

On the exposed bridge of the Olympia stood Dewey in white uniform, stroking his white mustache and estimating ranges. His impressive paunch and imperturbable bearing made him a figure of calm authority, rendered just a bit jaunty by the fact that he was wearing a golf cap. It seems that in jettisoning the wooden bulkheads somebody had inadvertently tossed over the commodore’s unifoiTn cap.

When Spanish shells began to fly overhead and splash near the flagship, Dewey, still estimating ranges, remarked to Lieutenant Corwin Rees, the executive oflRcer, “About 5,000 yards, I should say, eh, Rees?”

“Between that and 6,000, I should think, sir.”

Dewey then turned to the Olympias commanding officer and said almost casually, “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.”

For the Americans the Battle of Manila Bay proved something of an anticlimax. Dewey’s squadron, firing steadily, paraded back and forth past the Spanish fleet, hurling back attempts by two of Montojo’s ships to charge the American line. At 7:35 the Americans hauled off to check ammunition and eat breakfast, and then resumed the battle. By a little past noon all of the Spanish ships were sunk, burned, or abandoned, the shore batteries were silenced, and a white flag of surrender flew over the main government building at Cavite. The carnage and devastation in the Spanish ships were almost unparalleled in the history of fleet battles. The American squadron, on the contrary, was scarcely damaged. No Americans had been killed and only eight were slightly wounded. The Spaniards had fought gallantly but were

Admiral Montojo’s flagship Reina Cristina wrecked and abandoned.

Defeated by their inferior firepower, inferior ammunition, and their almost complete lack of training. Dewey’s careful preparations had paid off. “The Battle of Manila,” he said, “was won at Hong Kong.”

World History

World History

![United States Army in WWII - Europe - The Ardennes Battle of the Bulge [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/2015-05/1432563079_1428528748_0034497d_medium.jpeg)